A special transmission outside the scriptures

Not founded upon words and letters;

By pointing directly to [one’s] mind

It lets one see into [one’s own true] nature and [thus] attain Buddhahood.

Bodhidharma (mid 5th century-beginning 6th century)

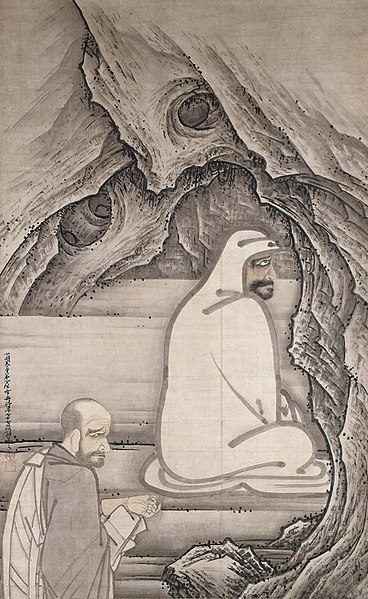

The above verses encapsulating Zen’s insight and practice are attributed to Bodhidharma, a Buddhist master born in Southern India, who landed in China after a three year voyage around 475, meditated for nine years facing a wall, had few disciples, and transmitted the basics of Zen to one of them before passing away in 528. These verses, however, were first found in a text dating from 1108, that is, 500 years after Bodhidharma’s death. And this is only one of the many difficulties scholars have faced when trying to reconstruct the life and teachings of the man regarded by millions of Chinese practitioners as he who brought Zen to their country.

Red Pine, who translated four writings attributed to him, admits that he has met at least one scholar prepared to accept that Bodhidharma never existed. Most scholars have settled for a characterisation of Bodhidharma as a “semi-legendary” figure. He is said to have been the third son of a Pallava king, and to have been taught by Prajnatara, a Buddhist master from Magadha, the birthplace of the Buddha, at the time part of the Gupta empire. Nothing, however, is known of a characteristically Zen Buddhist school in the Pallava kingdom, and to complicate matters, other texts claim that Bodhidharma came from Central Asia. It is said that, upon his arrival in China, he met the Emperor Wu of the Liang dynasty who asked him how much merit he had gained from performing religious works, to which Bodhidharma dryly replied “no merit.” This famous episode is undoubtedly a splendid display of the iconoclasm characteristic of the Zen tradition. It is, however, absent from the early records.

The name of Bodhidharma is often associated with the Shaolin Temple, as he is honored by kung-fu practitioners as the founder of their art. Red Pine accepts that, “coming from India, he undoubtedly instructed his disciples in some form of yoga, but no early records mention him teaching any exercise or martial art.” He also adds that the Shaolin Temple, built around the time Bodhidharma was present in the country, was not built for him, but for another master, and Bodhidharma spent his nine years gazing at a wall in a cave a mile away from the temple. The ever popular Daruma doll shows a bearded meditator who had sat for so long that his arms and legs had fallen off. Bodhidharma is also said to have cut his eyelids to avoid falling asleep during his lengthy sittings, and out of his eyelids it is said that tea plants grew, which makes him the man who brought tea to China, as well as Zen … Last, the story goes that after his death, he was seen walking in Central Asia, supposedly on his way home, carrying a staff from which hung a sandal. His tomb was subsequently opened, and in it was found a second sandal.

Zen or Ch’an

In the Noble Eightfold Path, dhyana, from which the name of the Zen school derives, is one of the eight practices listed, in fact, the last one, indicating that only once a discipline of the body has been achieved, can one expect to be able to correctly embark on a training of the mind. Dhyana is the Sanskrit translation of the Pali jhana, a type of concentration with eight levels of attainment, which the Buddha himself had practiced during his quest as a sramana. When dhyana was brought to China, the word was pronounced zen-na, and later shortened to zen. According to Red Pine, this was how it was called at the time of Hui-neng, said to be the second founder of the Zen school. It is only in the 17th century that, under the pressure of the Manchu dynasty, the name of school was pronounced ch’an. More significantly, the sitting practice known as zazen, that has become the core practice of the Zen school, is no longer one that involves levels of concentration. It is described as a pointing to the mind, the emphasis now being on non-interfering with the natural functioning of the mind.

The quest for a lineage

Notwithstanding the radical move Zen represented in its approach to the mind, and the new centrality it gave it, there arose a need to create an explicit line of transmission from the teachings of the Buddha to those of Hui-neng, on which Zen teachings are more directly based. In fact, eminent Mahayana thinkers such as Nagarjuna, Asanga, Vasubandhu, and Fa-tsang, had also been keen to show that their teachings had their origins in the Buddha’s teachings. Hui-neng being a pure bred Chinese, an Indian master “bringing Zen from the West” as Bodhidharma is called, would have had to be invented, had he not to some extent existed!

to Bodhidharma

Peter Harvey explains that, in the 8th century, a harsh controversy fractured the Zen/Ch’an school with the Southern school emphasising that, “for the wise, awakening comes suddenly,” while attributing “to the flourishing Northern school the view that it is arrived at in stages, by a gradual process of purification.” Hui-neng, the illiterate “barbarian from the South” who had secretly received the robe as symbol of the patriarchship from Hong-jen represented the Southern School, and had become the Sixth Patriarch of the Zen school.

Between Bodhidharma, the first Patriarch, and Hui-neng, different versions of the lineage lists different names, mostly unknown, except for Huike, the disciple who is said to have cut off his arm to offer it to Bodhidharma in order to receive his teachings, and Hong-jen, who had chosen Hui-neng as his successor. At the same time, Bodhidharma was said to be the 28th Patriarch in the lineage linking him to the Buddha. Through Prajnatara, the Bodhidharma’s teacher, is listed as the 27th, the emergence of a distinctly Zen teaching is associated with Mahakashyapa, a direct disciple of the Buddha.

Mahakashyapa – a flower and a smile

In the Flower Sermon, it is said that one day the Buddha sat before the assembly of monks and laity, but instead of speaking, he only held (or twirled) a flower and winked. Of all those present, only Mahakasyapa responded – by smiling. This smile is regarded as the first transmission “beyond words and letters” taken to be the core teaching of Zen. It is an intuitive transmission from mind to mind, at the level of experience, which reflects a distinctive East Asian relation with reality.

The “stories” are teachings

When we explore the origins of Buddhist schools such as the Madhyamika, the Yogacara or Huayan, we normally look for evidence of earlier versions of of similar ideas in the Mahayana sutras. Though it is clear that Zen’s insights can also be traced to sutras such as the Nirvana, the Lankavatara and the Diamond sutras, among others, what is striking in the case of Zen is the many “stories” we are being told about the key founders – Mahakyasapa, Bodhidharma and Huineng. Beyond the effort to support the nascent Zen school in the 7th and 8th century by linking it to an Indian founder and, through him to a direct disciple of the Buddha, the stories are also used to teach the principles of Zen rather than refer to actual historical events. This is obvious for Mahakyasapa’s smile, and it is similarly obvious in Bodhidharma’s nine years gazing at a wall, clearly a metaphor for his new emphasis on zazen as the practice of pointing to one’s own mind.

Hui-neng (638-713)

Red Pine tells us that Hui-neng is similarly a semi-legendary figure. The account of his life story, at the beginning of the Platform Sutra, may have been, at least in part, the creation of his disciple Shen-hui, to give legitimacy to the Southern School at the expense of the Northern School.

At the same time, the particulars of Hui-neng’s social origins, his illiteracy, the verse contest, and the Dharma transmission he received from Master Hong-jen, are also to be read as an exposition of the “sudden enlightenment” teaching of the Southern School.

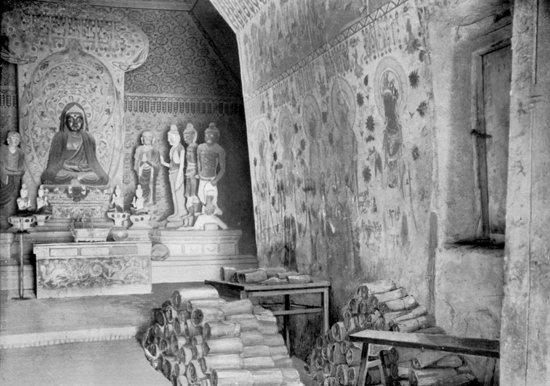

I will follow Red Pine’s translation of the text, based on a manuscript recovered from the Dunhuang Cave, which is earlier than the Tsung-pao edition, the text millions of Buddhists have been reading throughout the centuries.

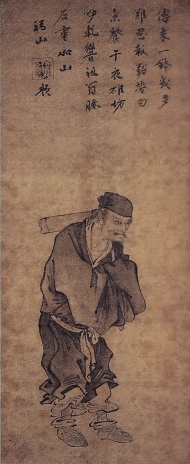

Hui-neng tells us in the first part of the Platform Sutra that, though belonging to an aristocratic family, he had known hardship and poverty in his youth, as his father had been dismissed from office, and banned to a rough part of the kingdom, where he had died when Hui-neng was still young. Hui-neng’s widowed mother had been unable to provide him with an education, so he was illiterate, and had to sell firewood for a living.

One day, as he was delivering firewood to a shopkeeper, he heard a customer recite the Diamond Sutra. “Where did you get this scripture you’re reciting?” asked Hui-neng. The man had learned it from the monks at Master Hung-jen’s monastery, and been told that “just by memorizing the Diamond Sutra they would see their natures and immediately become buddhas.” “As soon as I heard the words,” Hui-neng recalled, “my mind felt clear and awake.” Hui-neng immediately set off for the monastery.

Red Pine comments that this spontaneous understanding indicates that Hui-neng, though poor and illiterate, was actually a bodhisattva getting near the end of his training. Others have seen his illiteracy as a metaphor for a mind that was closer to enlightenment because it was free from the conceptual layers which education heaps on top of our pure original mind.

Hui-neng’s first meeting with Master Hung-jen was not encouraging. Upon hearing that he had come from the South, he called Hui-neng a “jungle rat” to which an unfazed Hui-neng replied, “People come from the north or south, not their buddha nature. The lives of this jungle rat and the Master’s aren’t the same, but how can our buddha nature differ?” Hui-neng was then sent to the milling room, where he “pedaled a millstone for more than eight months.”

A story of two poems to gain the patriarchship

One day, Hong-jen, the Fifth Patriarch, told an assembly of his disciples that “the greatest concern for a human being is life and death.” In order to check their understanding, and select a worthy recipient for the patriarchship, he invited “those who are wise” to “make use of the prajna wisdom of [their] own nature” to write a gatha. Upon reading the gathas, he would know if any of the monks understood “what is truly important,” and give him the robe symbolising his appointment as the Sixth Patriarch.

Red Pine notes that “poetry was … the quintessential form of expression in China. The original meaning of the Chinese word for poetry, shih, was “words from the heart.” Hence, Zen masters don’t ask for a dissertation, just a poem.” Zen can be seen as the response to the cultural shock Buddhism had to overcome when the lengthy Indian Buddhist treatises and sutras – often including dozens of scrolls or volumes – landed in a culture seeking an all-encompassing intuitive grasp of the living world.

Taking as a given that their precept instructor Shen-hsiu, would be selected, none of the monks bothered to write a gatha. Shen-hsiu, however did, and this is the gatha he wrote on the wall.

The body is a bodhi tree

the mind is like a standing mirror

always try to keep it clean

don’t let it gather dust.

Hong-jen did accept the gatha, and asked that it remains on the wall, giving as justification that if the monks “rely on it for their practice, they won’t fall into the three unfortunate states of existence.” He also told Shen-hsiu that “someone with such an understanding who seeks perfect enlightenment will never realize it.” Shen-hsiu was then asked to go back to his room, and write another gatha, which he was unable to do.

Stuck in the milling room, Hui-neng had not even heard of Master Hong-jen’s request for a gatha, but, once again, he came across a novice reciting Shen-hsiu’s gatha, asked to be taken to where it was written, and be read to him. The two following gathas, which Hui-neng had another monk write for him, were his response:

“Bodhi doesn’t have any trees

this mirror doesn’t have a stand

our buddha nature is forever pure

where do you get this dust?”

“The mind is the bodhi tree

the body is the mirror’s stand

the mirror itself is so clean

dust has no place to land.”

The rest, as one is tempted to say, is history, except that it is most probably just a story! As they read Hui-neng’s gathas, the monks were “dumbfounded” and soon Master Hung-jen came down the corridor, and, as Hui-neng recalls “He knew I understood what was truly important, but he didn’t want others to know. So he told everyone, “This one doesn’t get it either.”

Red Pine comments: “The only truth worth knowing is the truth of your own mind. But there is our mind, and then there is the mind we have been trained to believe is our mind. The one gives birth to wisdom, the other to delusion. Shen-hsiu offers a poem rooted in the dialectics of delusion, while Hui-neng responds with a poem born from the emptiness of wisdom.“ Shen-hsiu’s gatha reflected the standpoint of the dualistic mind, Hui-neng’s that of the standpoint of the awakened mind, i.e., that of emptiness.

Hong-jen then asked Hui-neng to come to his room. Having explained to him the Diamond Sutra, he gave Hui-neng the robe as “an embodiment of trust that has been handed down from one generation to the next.” But, Hui-neng adds, “the Dharma is transmitted from mind to mind and must be realized by people themselves.”

In the troubled times when this drama unfolded, receiving the robe was a mixed blessing. Hong-jen told Hui-neng, “since ancient times the lives of those to whom this teaching has been transmitted have hung by a thread. If you stay here, someone will harm you. You must leave at once.” Hui-neng did as told, and did not reveal himself as the Sixth Patriarch for many years.

A detailed presentation of the teachings on which the Southern School, and Zen itself, are based, follow this account. I offer a summary of these teachings in the following text, “Hui-neng – The Platform Sutra.”

Sources

Red Pine (Bill Porter) – The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma (1987)

Red Pine (Bill Porter) – The Platform Sutra – The Zen Teaching of Hui-neng (2006)

Peter Harvey – An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practice (2013)