“Emptiness in the sense of sunyata is emptiness only when it empties itself even of the standpoint that represents it as some “thing” that is emptiness. It is, in its original Form, self-emptying … True emptiness is not to be posited as something outside of and other than “being.” Rather, it is to be realized as something united to and self-identical with being” (Religion and Nothingness p 96-7).

Nihilism in today’s world: standing outside the laws of nature, in the pursuit of our desires unreservedly

The beginning of Essay 3 focuses on the impact of science and technology on contemporary culture, how they have given rise to “a mode of being in which man behaves as if the stood entirely outside the laws of nature .… a mode of being at whose ground nihility opens up … which is … the mode of being of the subject that has adapted itself to a life of raw and impetuous desire, of naked vitality … as it pursues its own desires unreservedly” (RN 85- 86) which I covered on the page on “Crypto-Nihilism – A Life of Raw and Impetuous Desire.” Nishitani regards this particular form of nihilism as the way nihilism discloses itself to us in the current phase of human history.

Heidegger, with whom Nishitani studied for two years, shared a similar anxiety about the impact of technology on human lives, which he investigated in The Question Concerning Technology (1954). Heidegger had also grappled with nothingness, with statements such as “the being of beings discloses itself in the nullifying of nothingness“ (Was ist Metaphysik? quoted by Nishitani, RN 109). But, again, having looked closely at Heidegger’s understanding of nothingness, Nishitani concluded that in his work “traces of the representation of nothingness as some ‘thing’ that is nothingness still remain” (RN 96).

Sunyata/emptiness is a dynamic, not a thing: it is a self-emptying

Nishitani then focuses on Buddhist sunyata, and states: “Emptiness in the sense of sunyata is emptiness only when it empties itself even of the standpoint that represents it as some “thing” that is emptiness. It is, in its original Form, self-emptying … True emptiness is not to be posited as something outside of and other than “being.” Rather, it is to be realized as something united to and self-identical with being” (RN 96-7).

Sunyata is “a self-emptying,” a dynamic, an activity, a process. It is “self-identical with being,” a concept similar to Nishida’s “self-identity of absolute contradictories.” This is a notion Nishitani likes to express through the word “sive,” which is equivalent to Nishida’s “soku,” and could be translated as “or.” For example, death-sive-life, negation-sive-affirmation. Here he says: “When we say “being-sive-nothingness,” or “form is emptiness; emptiness is form,” we do not mean that what are initially conceived of as being on one side and nothingness on the other have later been joined together. In the context of Mahayana thought, the primary principle of which is to transcend all duality emerging from logical analysis, the phrase “being-sive-nothingness” requires that one take up the stance of the “sive” and from there view being as being and nothingness as nothingness” (RN 97). This is what he calls “a standpoint of absolute non-attachment” that is shackled to neither being nor nothingness, and views them as “co-present and structurally inseparable from one another.”

“Emptiness lies absolutely on the near side, more so than what we normally regard as our own self”

Another expression Nishitani often uses is: “Emptiness lies absolutely on the near side, more so than what we normally regard as our own self. Emptiness, or nothingness, is not something we can turn to. It is not “out there” in front of us” (RN 97). The expression “near side” replaces “within” which Nishitani needs to avoid, since what we perceive as happening within ourselves in introspection, for instance” is still perceived by our ordinary consciousness as an “object.” What “near side” refers to is too close to be perceived but still impacting our behaviour toward the world, in fact being more “ourselves” than when we are acting self-consciously. Nishitani remarks that “the self shows a constant tendency to comprehend itself representationally as some “thing” that is called “I.” This tendency is inherent in the very essence of the ego as self-consciousness.” Yet, this representation of the self conceals its true subjectivity, which is an activity, and not a thing. Only “from the standpoint of Existenz-in-ecstasy,” when we no longer see that self as a representation, we, as it were, forget our self, “held in nothingness,” does “a standpoint of truly subjective self-consciousness [appear]” (RN 97-98).

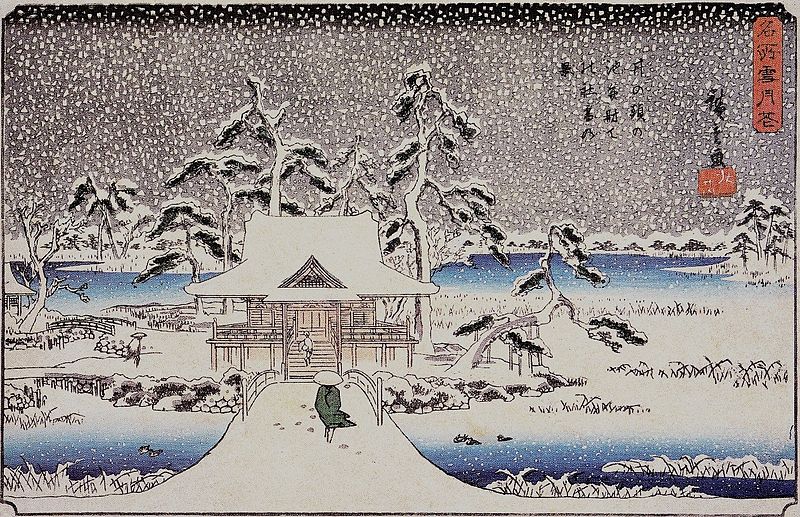

As it is not easy for us to deliberately “forget” our ego-self, it may be helpful to use a detour, and embrace emptiness through feelings of awe. Whatever nihility we encounter then must be seen against the background of the emptiness at the ground of all things. “As a valley unfathomably deep may be imagined set within an endless expanse of sky, so it is with nihility and emptiness. But the sky we have in mind here is more than the vault above that spreads out far and wide over the valley below. It is a cosmic sky enveloping the earth and man and the countless legions of stars that move and have their being within it. It lies beneath the ground we tread, its bottom reaching beneath the valley’s bottom” (RN 98). In fact, just as we overlook the cosmic sky that envelops us while we move and have our being within it, and stare only at the patch of sky overhead, so too we fail to realize that we stand more to the near side of ourselves in emptiness than we do in self-consciousness” (RN 98).

Though Nishitani regarded Plotinus’ philosophy as still “shackled” to being, Pierre Hadot writes that the Neo-Platonist philosopher made a very similar statement when he said that “the whole paradox of the human self is there: we are only what we are conscious of, and yet we feel that we are more ourselves … when, raising ourselves to a higher level of inner simplicity, we have lost consciousness of ourselves.” This reflected Plotinus’ own experience of moving in and out of a conscious identification with his own self, and the feeling that he was more fully himself when he was not conscious of himself, though he could only become aware of this at the moment when the consciousness of himself returned!

Nihility is “a reality every bit as real as our actual existence”

As already noted, this discussion follows an analysis of the way the rule of the laws of nature over humans has become so deep, due to the development of science and technology, that it has opened up “a mode of being in which man behaves as if the stood entirely outside the laws of nature” which he equates with “a mode of being at whose ground nihility opens up” (RN 85). So one would be tempted to see that particular predicament as the nihility Nishitani is talking about. It is to a point, but, as Nietzsche also contended, nihility is inherent in the human condition, as a by-product of self-consciousness. “Nihility is … “a reality every bit as real as our actual existence. Nor is nihility something removed from the ordinary level on which we live. It is something in which we find ourselves every day. Simply because our every day is all too “everyday,” because we are so stuck in our everydayness, we fail to pay attention to the reality of nihility” (RN100).

For instance, Nishitani asks, we think we know our family and our friends, but do we? “We no more know whence our closest friend comes and whither he is going than we know where we ourselves come from and where we are headed. At his home-ground, a friend remains originally and essentially a stranger, an “unknown” … Even as we sit chatting with one another, the stars and planets of the Milky Way whirl about us in the bottomless breach that separates us from one another” (RN 101). This is also true in the case of things. “Take the tiny flower blooming away out in my garden. It grew from a single seed and will one day return to the earth, never again to return so long as this world exists. Yet we do now know where its pretty little face appear from nor where it will disappear to. Behind it lies absolute nihility … Separated from me by the abyss of that nihility, the flower in my garden is an unknown entity … The reality of this nihility is covered over in an everyday world which is in its proper element when it traffics in names. The home-ground of existence passes into oblivion” (RN 101).

It could be said that we constantly avert our eyes from that nihility by focusing on the external knowledge we have of things and beings, for practical reasons, that is, because we tend to see things and beings in relation to our ego-centred needs and desires. We are more keen to apprehend what they are for us than what they are for themselves! So only after converting from the field of ego-centredness to the field of emptiness can we achieve an “intimate encounter with everything that exists,” which “takes place at the source of existence common to the one and the other and yet at a point where each is truly itself” (RN 102). In fact, Nishitani thinks that one can no longer speak of an “encounter.” It is more as if we were manifestations of one unified reality. “Just as a single beam of white light breaks up into rays of various colors when it passes through a prism, so we have here an absolute self-identity in which the one and the other are yet truly themselves, at once absolutely broken apart and absolutely joined together. They are an absolute two and at the same time an absolute one” (RN 102). Nishitani here quotes a well-known Zen verse by Zen Master Daito Kokushi, which Nishida also quoted: “Separated from one another by a hundred million kalpas, yet not apart a single moment; sitting face-to-face all day long, yet not opposed for an instant” (RN 102).

Essay 3 ends with a brief consideration of the Western standpoint of being, first expressed in terms of substance in the Aristotelian standpoint of reason, and later as the standpoint of consciousness, based on the opposition between subject and object, in its modern post-Cartesian reformulation. He then constrasts this standpoint with that of emptiness, using the Diamond Sutra’s well-known formula “This is not fire, therefore it is fire.” Discussion on this complex formula is covered on the page entitled “The Logic of Soku.”

Sources:

Nishitani Keiji – Religion and Nothingness

Pierre Hadot – Plotinus and the Simplicity of Vision, own translation)