In nourishing the soul and embracing the One – can you do it without letting them leave?

In concentrating your breath and making it soft – can you make it like that of a child?

In cultivating and cleaning your profound mirror – can you do it so that it has no blemish?

In loving the people and giving life to the state – can you do it without using knowledge?

In opening and closing the gates of Heaven – can you play the part of the female?

In understanding all within the four reaches – can you do it without using knowledge?

Give birth to them and nourish them.

Give birth to them but don’t try to own them;

Help them to grow but don’t rule them.

This is called Profound Virtue.

(Translation by Robert Henricks)

In the introduction to his translation of the Tao Te Ching, Robert Henricks writes: “The importance of meditation in early Taoism and the role it played in Taoist experience are points about which scholars disagree. Would Lao-tzu have insisted that the only way to return to the Tao is by means of meditation and mystical experience? Did he and other Taoists have definite techniques that they followed in meditation? Answers to these kinds of questions do not come easy. The most we can say is that if Lao-tzu and his like practiced and advocated certain types of meditation, for some reason he chose not to elaborate on these techniques in his book.”

The Nei-yeh (Inward Training)

Harold Roth’ Original Tao has, I believe, thrown light on this issue. Along with the copies of the Tao Te Ching buried in the Ma-wang-hui tomb, a number of other texts buried there as well as in other tombs, were recovered. These discoveries sparked something of a revolution in our understanding of the origins and early development of Chinese culture. It also prompted scholars to take another look at texts already known. Among these was the Kuan Tzu, a voluminous collection of 76 texts almost entirely devoted to political and economic thought. But “buried intellectually” within this collection was a mystical work, on which Harold Roth published under the title “Original Tao – Inward Training (Nei-Yeh) and the Foundations of Taoist Mysticism.” In Roth’s words, “among all the works in the spectrum of late Warring States and early Han thought, it is the one that most closely parallels the Lao Tzu in both literary form and philosophical content.” The study of this book has gone a long way in settling the uncertainty surrounding the issue of self-cultivation practices in early Taoism. Roth writes: “A C Graham has called the Nei-yeh (“Inward Training”) ‘possibly the oldest mystical text in China’.” It represents the earliest extant presentation of a mystical practice that appears in all the early sources of Taoist thought, including the Lao-tzu, the Chuang-tzu and Huan-nan Tzu.”

Roth continues: “Inner Training is a series of poetic verses devoted to the practice of guided breathing meditation and to the ideas about the nature of human beings and the cosmos that are directly derived from this practice. It is a mystical text because its authors followed this practice to depths nor normally attained by daily practitioners of breathing for health and longevity, with whom they shared aspects of technical terminology and world view … while both groups practices guided breathing meditation, the early Taoists applied this practice much more assiduously. In Inward Training, the noetic insights attained from this assiduous application of breathing meditation are the basis of the distinctive cosmology of the text, a cosmology similar to that found in its more renowned companion, the Lao-tzu.”

Inward Training as the common mystical practice that ties together the three phases of early Taoism

In Roth’s view, there is a “common thread that ties together [the] three philosophical orientations of early Taoism,” which are 1) “a cosmology based on the Tao as the predominant unifying power in the cosmos; 2) inner cultivation, i.e., “the attainment of the Tao through a process of emptying out the usual contents of the conscious mind until a profound experience of tranquillity is attained; and 3) “the application of this cosmology and this method of self-cultivation to the problems of rulership.” This common thread, Roth argues, is a “shared vocabulary that derives from a common meditative practice first enunciated in Inward Training, which I call “inner cultivation.” This inner cultivation practice and the cosmology that surrounds it seems to have been carried over into the mystical practices of the later Taoist religion, although the historical details by which this transmission occurred are so obscure that perhaps they will never be known for certain.” Roth does, however, show that “the three groupings of early Taoist texts were produced by actual historical groupings of individuals.” He then concludes that “Inner Training” is best understood as the earliest extant statement of the one common mystical practice that ties together the three phases of early Taoism … Furthermore, there is considerable reason to believe that it was actually written earlier than [the Lao-tzu and the Chuang-tzu]. Hence the title “Original Tao.”

“The Nei-yeh is about one third as long as the Tao Te Ching. The first character, nei, means “inner/inward”. The second character, yeh, means “work, deed, achievement.” Hence “The Workings of the Inner” (Riegel), “Inner Workings” (Rickett) or “Inner Training.” Its author, echoing Socrates’s “the unexamined life is not worth living,” held that “a life, left to its own devices, will waste the great potential of human beings for physical, psychological, and spiritual fulfillment. However, if this inner life is led with self-discipline, it can lead to health, vitality, psychological clarity, a sense of well-being, a profound tranquility, and, ultimately, to a direct experience of the Way and an integration of this experience into one’s daily life. To lead this disciplined life is the practice advocated by this text … It refers to the practice by which one cultivates and nourishes the inner mind and preserves vital essence and vital energy … While the author of this text points out the important of proper drinking, eating, and physical movement, the most basic and emphatic point lies completely within the inner mind. Therefore he called it Inward Training.”

On the basis of a comparison with the structural and phonological characteristicsm of the Lao-tzu and other texts, including the other texts of the Kuan Tzu collection, William Baxter has dated the text to about 400 BCE. Though scholars are still arguing about the date, Roth says that, based on the absence of reference to “the correlative cosmology of yin and yang and the five phases, characteristics of 3rd century BCE texts,” he believes that the Nei-yeh goes back to the 4th century BCE.

The Text

Roth provides the full text in Chinese and in its English translation. Inward Training was originally a lengthy undivided text, but scholars have now divided it into 26 “verses.” I obviously can only present a glimpse of these verses to give the reader a taste of what Inward Training is like.

Verse I to VII lay the philosophical foundations of the practice, and focuses on the closely related concepts of the vital essence and the Way. Verses I and IV focus on the “nature” of Tao itself.

Verse I

The vital essence of all things:

It is this that brings them to life.

It generates the five grains below

And becomes the constellated stars above.

When flowing amid the heavens and the earth

We call it ghostly and numinous.

When stored within the chests of human beings,

We call them sages.

Verse IV

Clear! as though right by your side.

Vague! as though it will not be attained.

Indiscernable! as though beyond the limitless.

The test of this is not far off:

Daily we make use of its inner power.

That Way is what infuses the body,

Yet people are unable to fix it in place.

It goes forth but does not return,

It comes back but does not stay.

Silent! none can hear its sound.

Suddenly stopping! it abides within the mind.

Obscure! we do not see its form,

Surging forth! it arises with us.

We do not see its form,

We do not hear its sound,

Yet we can perceive an order to its accomplishments.

We call it “the Way”.

The Way is described as a dynamism that we can never fully grasped. It is neither the reassuring manifestation of a Buddha nature that pervades all things in the cosmos, or the will of God that is assumed to be rational and just. This all boils down to the fact that, in Taoism, Tao, the Way is the product of the vital energy (ch’i), a rather exhuberant and unpredictable energy.

So, “The Way is always present. However, the awareness of this presence enters the human mind only when it is properly cultivated.” Given the mystery within which the Way is shrouded, it is no wonder that inner cultivation is presented as a securing of “tranquility.”

Roth writes: “The attainment of tranquility is one of the central concepts and goals of Inward Training. For the Inward Training authors, the attainment of tranquility is always preceded by the practice of cheng, which literally means “to square up” or “to center” something, but is translated here as to “align.” The term implies adjusting or lining up something with an existing pattern or form. In fact, as their basic method of practice the authors of Inward Training advocate a “Fourfold Aligning”:

- aligning the body (cheng hsing)

- aligning the four limbs (cheng ssu t’i)

- aligning the vital energy (cheng-ch’i)

- aligning the mind (cheng-hsin)

The teaching of the “Fourfold Aligning” is laid out in the following verses:

Verse VIII

If you can be aligned and be tranquil,

Only then can you be stable.

With a stable mind at your core,

With the ears and eyes acute and clear,

And with the four limbs firm and fixed,

You can thereby make a lodging place for the vital essence.

The vital essence: it is the essence of the vital energy.

When the vital energy is guided, it [the vital essence] is generated,

But when it is generated, there is thought,

When there is thought, there is knowledge,

But when there is knowledge, then you must stop.

Whenever the forms of the mind have excessive knowledge,

You lose your vitality.

Verse XI

When your body is not aligned,

The inner power will not come.

When you are not tranquil within,

Your mind will not be well ordered.

Align your body, assist the inner power,

Then it will gradually come on its own.

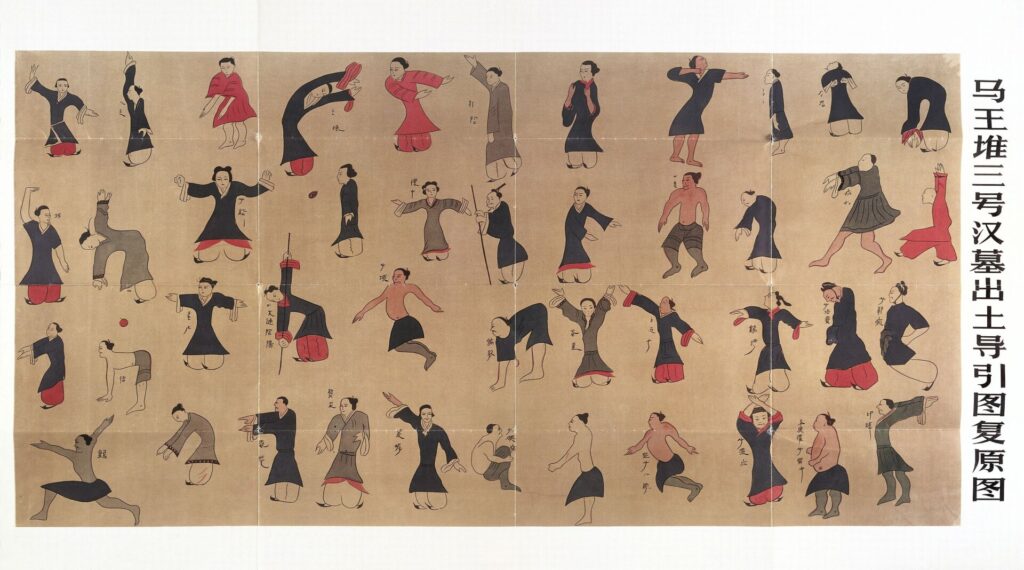

Roth comments: “In these two passages, being aligned precedes being tranquil, and both are the basis for developing a stable or concentrated mind and inner power and, ultimately, for lodging the vital essence. The aligning spoken of here is a physical one, in which one sits with the limbs fixed in a stable posture … “Aligning the body” and “aligning the four limbs” are closely related. From their basic meaning, they seem to refer to sitting in a stable posture in which the limbs are aligned or squared up with one another. Sitting in a stable position with the spine erect is a posture described in the macrobiotic hygiene text of Ma-wang-tui and Chang-chia shan. Therein, in such a posture, one practices a form of circulation of the vital energy. This is also the basic posture in which Buddhist meditation was practices in India and China. Chuang Tzu makes reference to such a posture in his famous passage on “sitting and forgetting.” So, aligning the body and aligning the four limbs appear to refer to a specific posture within which breath meditation was practiced. The meaning of the two phrases seems to suggest a posture in which the knees are touching the floor and perhaps the buttocks are seated on a thick cushion and the arms and shoulders are fixed in a position in which they line up to form a square pattern with the knees.

It is indeed the posture in which the Buddha is traditionally represented, even more often than Lao-tzu or Chuang-tzu or any other Taoist sage, so it must have originated in an early pre-literate cultural layer widely shared in Asia. In Inner Training, “this proper posture refers to the position for breathing meditation.”Though many schools of Buddhism teach a practice of meditation relying on the breath, for Dogen,who explicitly teaches this posture in the Fukan Zazengi (Universal Recommendations for Zazen), this was not the case. Shikantaza – just sitting – asks the practitioner to just allow thoughts to arise, and let them go, resisting the habitual temptation of getting caught by them.There is no mention of breathing. Even when Buddhist meditation focuses on the breath, it is more a matter of counting one’s inhalations and exhalations than using breath as vital energy to increase one’s power. Roth suggests that “Buddhism cut off the “physiological substrate” of this “inner power” which it therefore called “emptiness,” to avoid any connotation of “power.”

The summary of inner cultivation practice found in verse XXIV goes deeper into the practice.

Verse XXIV

When you enlarge your mind and let go of it,

When you relax your vital breath and expand it,

When your body is calm and unmoving:

And you can maintain the One and discard the myriad disturbances.

You will see profit and not be enticed by it.

You will see harm and not be frightened by it.

Relaxed and unwound, yet acutely sensitive,

In solitude you delight in your own person.

This is called “revolving the vital breath.”

Your thoughts and deeds seem heavenly.

“The Inward Training authors call this breathing “aligning the vital breath,” the third of the “Fourfold Aligning.” With your breathing relaxed and expanded by this practice, you let go of the various contents of your mind and become acutely sensitive. Verse XIX includes a related passage:

Verse XIX

… When the four limbs are aligned

And the blood and vital breath are tranquil,

Unify your awareness, concentrate your mind,

Then your eyes and ears will not be overstimulated.

And even the far-off will seem close at hand.”

There is a whole lot more that I would have liked to include in this entry. In my view, the issue of the existence of a self-cultivation practice among the sages who contributed to the Tao Te Ching has been settled with the discovery of the Nei-yeh. There, indeed, was a practice, and a sophisticated one. Another point Inward Training makes is that, when simply looking at the background to the foundational texts of Taoism, Ho-shang-kung’s commentary, which highlights the role of ch’i in the attainment of oneness with the Way, is more helpful than the later commentary by Wang Pi, which, perhaps under the influence of newly arrived Buddhism, has already taken a step back away from Taoism’s root in the equation of Tao, or at least, the “One” produced by Tao, with the vital energy pervading the cosmos.

Sources:

Robert G Henricks – Lao-Tzu, Te-Tao Ching

Harold D Roth – Original Tao, Inward Training (Nei-yeh) and the Foundations of Taoist Mysticism