“Since olden times, the cognitive power of reason has been called a “natural light.” But the real “natural light” is not the light of reason. It is rather, if I may designate it, the light of each and every thing. What we call the knowing of non-knowing is, as it were, the gathering together and concentration on a single point of the light of all things. Or better still, it is a reverting to the point where things themselves are all gathered into one” (Nishitani Keiji – Religion and Nothingness p 140).

Nishitani writes: “After Kant, “modern man’s subject-oriented standpoint ran its course precipitously until it could go no further. Eventually it reached the standpoint of reason, of absolute reason; and then, breaking through still further, it laid bare the nihility at its own ground” (RN 135). We found ourselves living in a world that was merely a projection of the a priori structures of our minds. At the very beginning of the book, Nishitani had defined nihility as “that which renders meaningless the meaning of life” (RN 4). It is a sense that “everything is the same” (RN 4). He talks about “the meaninglessness that lies in wait at the bottom of those very engagements that bring meaning to life” (RN 4). Here Nishitani says that “the nihility that opens up at the ground of the subject by breaking through that field of reason is simultaneously ‘inserted into’ (hineingelegt) the ground of the totality of things … With that, the existence of things and of the self are both transformed into something utterly incomprehensible, of which we can no longer say ‘what’ it is … On the field of nihility, where the field of reason has been broken through, cognition is no longer the issue … Once on the field of nihility, objects (things and the self as objects) and their cognition cease to be problems; the problem is the reality of things and the self. Moreover, this reality and our apprehension of it are made possible not by returning from the field of nihility to the field of reason, but only by advancing from the field of nihility to arrive at a field where things and the self become manifest in their real nature, where they are realized” (RN 136-37). Which is, of course, the field of sunyata. The Zen practice of the Great Doubt aims at triggering the same breakthrough of the field of reason, what Dogen also called “dropping body and mind.”

This leads Nishitani to return to his own view of the mode of being of the things in themselves on the field of emptiness. “On the one hand, the thing itself is truly itself on this field, for in contrast with what is called objective reality, it has shaken off its ties with the subject. This does not mean, however, that it is utterly unknowable. For reason, it is indeed unknowable; but when we turn and enter into the field of emptiness, where the thing itself is always and ever manifest as such, its realization is able to come about” (RN 139). So the thing cannot be “known” but it can be “realised” in the sense of “actualised” as Nishitani uses the word throughout the book. “On the other hand, on this field the being of a thing is at one with emptiness, and thus radically illusory. It is not, however, an illusory appearance in the sense that dogmatism uses the word to denote what is not objectively real. Neither is it a “phenomenon” in the sense, say, that critical philosophy uses the word to distinguish it from the thing-in-itself. A thing is truly an illusory appearance at the precise point that it is truly a thing in itself” (RN 139).

Earlier on Nishitani had compared the shapes that things assume on the field of sensation and display on the field of reason as “radiations from the things themselves, like rays issuing from a common source.” Here Nishitani uses a traditional Buddhist saying to elucidate his insight. “As the saying goes, ‘A bird flies and it is like a bird. A fish swims and it looks like a fish.’ The selfness of the flying bird in flight consists of its being like a bird; the selfness of the fish as it swims consists of looking like a fish. Or put the other way around, the ‘likeness’ of the flying bird and the swimming fish is nothing other than their true ‘suchness’. We spoke earlier of this mode of being in which a thing is on its own home-ground as a mode of being in the ‘middle’ or in its own ‘position’. We also referred to it as ‘samadhi-being’” (RN 139).

Nishitani’s conclusion is that “On this field of emptiness, modern man’s standpoint of subjective self-consciousness, which had been opened up by Kant’s Copernican Revolution, has to be revolutionized once again. We appear to have come to the point that the relationship in knowledge whereby the object is said to fashion itself after our a priori patterns of intuition and thought has to be inverted yet again so the self may fashion itself after things and correspond to them.”

This is also what Dogen had said in his well-known verses: “To study the Buddha Way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be actualized by all things.” On the field of reason, the subject seeks to “know” the object. When the self is “forgotten,” one is, as it were, thrown on the field of emptiness where, as Nishitani stated above, the thing in itself is always and ever manifest as such,” and “its realization [as actualization] is able to come about.” Nishitani further defines “realization” as “‘manifestation-sive-apprehension’ of the thing itself, which cannot be prehended by sensation or reason. This it not cognition of an object, but a non-cognitive knowing of the non-objective thing in itself; it is what we might call a knowing of non-knowing, a sort of docta ignorantia … The thing in itself becomes manifest at bottom in its own ‘middle’, which can in no way ever be objectified. Non-objective knowledge of it, the knowing of non-knowing (non-cognitive knowing), means that we revert to the ‘middle’ of the thing itself” (139-140). Nishitani adds that “middle” should not be taken to mean “inside.”

Nishitani concludes Section IV with the words: “Since olden times, the cognitive power of reason has been called a ‘natural light’. But the real ‘natural light’ is not the light of reason. It is rather, if I may designate it, the light of each and every thing. What we call the knowing of non-knowing is, as it were, the gathering together and concentration on a single point of the light of all things. Or better still, it is a reverting to the point where things themselves are all gathered into one” (RN 140).

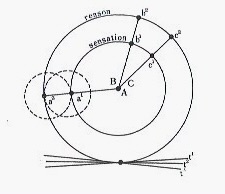

In Section V, Nishitani further explains what he has in mind with a drawing where the fields of sensation and reason are represented as the circumferences of two concentric circles. Now, he writes, “let a single radius cross the two circumferences at two points, designated as a1 and a2, to represent the objective forms under which a certain thing, A, appears on the fields of sensation and reason respectively. This means, in effect, that a1 and a2 are actually a1(A) and a2 (A). Meantime, the thing itself, A, is situated in the center of the circle. This mode of being of a thing as it is in itself, as a nonobjective way of being-in-the-middle, permeates a1 and a2 such that they can be seen as apparitions of A itself: A is A(a1, a2). All other things, B, C, D …, can be represented in the same way. The infinity of possible points on the circumferences a1, b1, c1 … or a2, b2, c2 …(up to an, bn, cn, …) are each conceived as distinct point, while in the center the infinite number of points , A, B, C …, are situated in the same center, concentrated into one. On the fields of sensation and reason, things are each seen as a sensible thing with independent individuality, are as the ‘substantial form’ thereof. In the non-objective mode of being, which they share as things in themselves, they are all concentrated into one simultaneously (RN 141-142).

Nishitani does not deny that “viewpoints that speak of a concentration into the One have shown up in the West from time to time. Examples are numerous, beginning in ancient Greece with Xenophanes’s notion of “one and All” (“What we call all things, that is One”) and Parmenides’ idea of “Being” (“To think and to be are one and the same”), and including such thinkers as Plotinus, Spinoza and Schelling. The absolute One they had in mind, however, was either conceived of as absolute reason or, when it went beyond the standpoint of reason, at least as an extension of that standpoint in unbroken continuity with it. One could also say that this “absolute One” was not accessed through the “purgative fires” in which the ego-self “is transformed, along with all things, into a single Great Doubt.” In the West, “the One is seen as the point at which all beings may be ‘reduced’ to one.” It is “something ‘abstracted’ from the multiplicity and differentiations of all beings. In a system of being that excludes nothingness, the idea that ‘all beings are One’ leads to the positing of a One seen as mere non-differentiation. It is precisely from this sort of standpoint that absolute unity is symbolized as a circle or sphere” (RN 144).

On the other hand, “Since there is no circumference on the field of sunyata, ‘All are One’ cannot be symbolized by a circle (or sphere) … on the field of sunyata, the center is everywhere. Each thing in its own selfness shows the mode of being of the center of all things. Each and every thing becomes the center of all things and, in that sense, becomes an absolute center. This is the absolute uniqueness of things, their reality” … “All are One” can only really be conceived in terms of a gathering of things together, each of which is by itself the All, each of which is an absolute center. And the only field in which this is possible is the field of sunyata, which can have its circumference nowhere and its center everywhere. Only on the field of sunyata can the totality of things, each of which is absolutely unique and an absolute center of all things, at the same time be gathered into one … In its mode of being a ‘middle’, even the tiniest thing, to the extent that it ‘is’, is an absolute center, situated at the center of all things. This is its ‘being’, its reality. The ‘world’, then, is nothing but the gathering together of that ‘being’. It is the ‘All are One’ of all that is in that mode of being – that is, the real world we actually live in and actually see” (RN 146-147).

Nishitani then goes on to characterise the fact “that beings one and all are gathered into one, while each one remains absolutely unique in its ‘being’, as a relationship of ‘circuminsessional interpenetration’ in which all things are master and servant to one another” (RN 147).

Sources:

Nishitani Keiji – Religion and Nothingness

Graham Parkes – “Nishitani Keiji – Practicing Philosophy as a Matter of Life and Death” in The Oxford Handbook of Japanese Philosophy Ed. Gereon Kopf