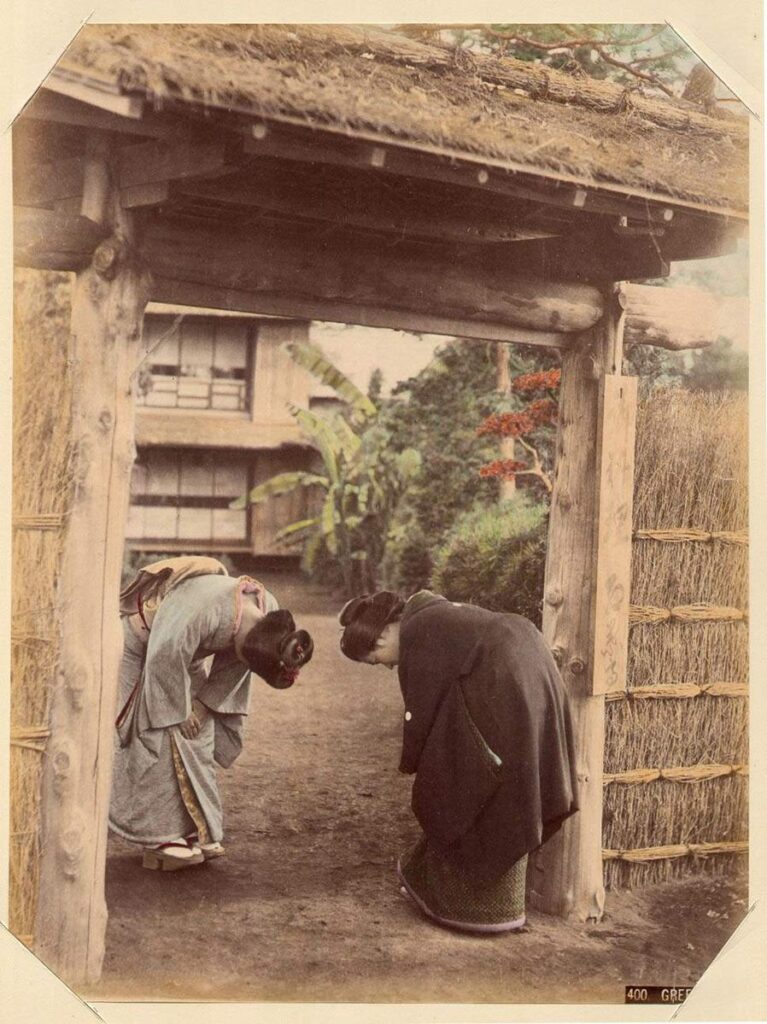

“As long as there is true bowing, the Buddha Way will not deteriorate” (Dogen)

Most people in the West see bowing as a thing of the East, and understand it as the social expression of the hierarchical order found in traditional societies: they who bow lower are publicly acknowledging their submission to the individuals who stand above them in the hierarchy. In the West too, whatever has survived of bowing is associated with elites – monarchy, Christian ceremonies at the highest levels.

Dogen, in the above quote, and Ueda Shizuteru, are looking at the meaning of bowing in Buddhism, which they take to be the true meaning of bowing, though neither goes into arguing whether it was the original meaning of bowing, or a Buddhist borrowing of an already existing social practice that emerged from the implementation of a hierarchical order. One question that has come to the mind of every newcomer to Buddhism in the West is: “Who, or what, do you bow to, when you bow in a Buddhist context?” I once was told – “you, in essence, bow to the Buddha within you, that is, your Buddha nature.” Keep in mind that in a monastic setting, you bow not only when meeting another person, but also when entering a room. And some monks joke about the time when they automatically bowed when entering the local store, and were stunned to see that the doors opened all by themselves in front of them!

On the more serious side, bowing in Buddhism should be lived not so much as a “bowing to” any particular entity, but as a moment of “self-negation” in the process of self-opening in a social setting.

Commenting on Ueda, Bret Davis contrasts the self-opening with the self-enclosure that lies at the basis of the Cartesian ego cogito as it asserts a self-sufficiency – what is often referred to as the assumption of “separate self” – that poisons social relationships in modern societies. Bowing as “the moment of self-negation in [the] movement of the true self is a matter of self-opening. The ego that merely asserts “I am I” does not include this moment of self-negation, and thus is not open to its coexistence with others. The modern cogito that presumes to be its own self-sufficient ground remains stuck in its self-enclosed self-consciousness and cuts itself off from an ecstatically empathetic relation with others. The moment of self-negation is thus the key to dialogue and a genuine I-Thou relation.”

Hand-shaking, which is customary in most cultures outside Asia, also conveys helpful values. Among other things, it conveys a sense of equality between the individuals as well as the affirmation of their willingness to engage with each other. But this is besides the point, as Ueda is here talking about bowing in the existential sphere of Buddhist practice. So he – and Davis -, can say that, in this context, “the emptying of all ego-centered presumptions and agendas – returns us to a communal place wherein we, paradoxically, share “nothing” in common.”

In Ueda’s own words:

“In the encounter with one another, rather than directly becoming “I and Thou” as in the case of a handshake, each person first lowers his or her head and bows. This does not stop at being a mere exchange of formalities. In the depths of “the between,” each person reduces himself or herself to nothing. Going from the bottom of “the between” into the bottomless depths that envelop self and other, each returns to a profound nothingness. Both persons, by means of bending their egos and lowering their heads […], return for a moment to a place where there is neither self nor other, neither I nor Thou. Then, by raising themselves up, they once again face one another and for the first time become “I and Thou.” Having each cut off the root of unilateral egoism, they become an “I and Thou” in which each is opened to their mutuality.”

So, it can be said that, “Open to others, by way of being open to the empty-expanse in which together we dwell, I am I.”

Ueda’s appeal to the notion of “empty-expanse” (koku, a traditional Buddhist term for the “empty space of non-obstruction”) is a reference to his concept of Being-in-the-Twofold-World,” whereby “the world as a comprehensive space of meaning is in turn located within the world of a limitless openness, a hollow-space of no-meaning that is without limits,” so, “insofar as we are in the world, we are located within this limitless openness” (Ueda).

Source:

Bret W. Davis – “The Contours of Ueda Shizuteru’s Philosophy of Zen,” in Tetsugaku Companion to Ueda Shizuteru, Ed. Ralf Müller, Raquel Bouso and Adam Loughnane (2022)