‘It is not that things ‘are,’ but that they ‘lean’, that they split themselves according to how they are inclined, and that this is what constitutes their ‘advance’: they are constantly toppling over due to their weight and hanging quality (the Latin pendere) in one way or another (the situational), and to prod-uce their future by this momentum and drive that they are taken forward to reconfigure themselves due to the sole fact that they are always, not a “being” but an inflection. Always the world is made only from the fact that everything, always, ‘leans’ towards what is ‘ahead’ in a certain way – pro-pendere – producing its renewal’ (François Jullien – From Being to Living p 2)

In From Being to Living, François Jullien, who describes himself as both a sinologist and an hellenist, summarises his lifelong inquiry ‘through a series of oppositions in order to conceptualise what he calls the écarts (divergences) between European and Chinese ways of thinking’. He insists that ‘it is not that European thought and Chinese thought are different in kind from one another in the sense that they represent differences of sensibility’. Rather, over the course of their different histories, European thought and Chinese thought have taken divergent paths based upon concepts that were established in ancient times and continue to condition, if not determine, what it is possible to think in different contexts … The point of divergence – lies in what has been given priority: following the concerns of Plato and Aristotle, Western thinking has been overwhelmingly concerned with the question of Being, whereas Chinese thinking concerned itself principally with that of living. Jullien insists on the importance of recognising this divergence, the result of a branching off of ways of thinking that has occurred over the course of their respective histories, failing which we are in danger of reducing all thinking to a single model, which will be that of the European’ (From Being To Living vii).

Jullien holds that it not possible for a Westerner to introduce Chinese thought head-on, as for instance some scholars have done using charts. For then, he says, ‘we would still inevitably be dependent, without being aware of the fact, on the implicit choices of our own language and thought … A displacement hasn’t occurred, we haven’t left home. We haven’t left ‘Europe with its ancient parapets’. The only strategy I can therefore see by which to emerge from this aporia is to organise the confrontation step by step, laterally … by means of successive sideways steps’ … to form a lexicon progressively, as we go along’ (FBTL x).

The first of these sideways steps is that of ‘Propensity (vs Causality)’.

Being versus Becoming in ancient Greece, Propensity encompassing both in ancient China

In ancient Greece, Jullien writes, “from an initial gesture which seems to be controlled by the approach of the mind, we [Europeans] have decided between the static and the dynamic, states that are either stable or shifting, with the latter even being regarded as contradictory due to the fact that it changes. Not that the inevitability of language inescapably stabilises things … but we can consider the situation on the one side and its evolution on the other. This precludes us from seeing things in their configuration at the same time as in their transformation’ (FBTL 1).

In China, on the other hand, the word ‘propensity’is used ‘to express how things are driven by what they ‘are’ and that they ‘are’ due to what drives them; how inclination is implied in the disposition and how, at the same time, the inclination itself constitutes the disposition – how the evolution is therefore not only contained in the configuration, but forms a union with it and is mingled in it’ (FBTL 1). Jullien adds: ‘I’ve found some support for this in shi, a term from ancient Chinese thought that … is variously translated by ‘situation’ or by ‘evolution’, by ‘condition’ or by the ‘course of things’. The word ‘propensity’ comes from the Latin pro–pendere,’meaning to ‘lean forward’. ‘It is not that things ‘are,’ but that they ‘lean’, that they split themselves according to how they are inclined, and that this is what constitutes their ‘advance’: they are constantly toppling over due to their weight and hanging quality (the Latin pendere) in one way or another (the situational), and to pro-duce their future by this momentum and drive that they are taken forward to reconfigure themselves due to the sole fact that they are always, not a “being” but an inflection. Always the world is made only from the fact that everything, always, ‘leans’ towards what is ‘ahead’ in a certain way – pro-pendere – producing its renewal’ (FBTL 2). Many scholars have used the term “process” to refer to the fact that what we daily call “things” are not the ‘solid’ entities they appear to be at first sight. Jullien says elsewhere that they are at all times ‘self-actualising’.

In Western thought, ‘to know’ is to know the cause of things’

To be sure, not so long ago, Buddhism was much admired for having best captured the concept of causality, as it had correctly expanded it to a serial causation process leading to entanglement and suffering in the doctrine of the Twelve Links (Nidanas), and in the interdependent causation of co-dependent origination (pratitya-samutpada).This assessment was based on the teachings of the Buddha as recorded in Theravada scriptures, and as such, inasmuch as it was opposing it, had been shaped by the heavily metaphysical mode of thinking of the mainstream Brahmanical culture based on the same Indo-European paradigm as ancient Greek philosophy. But Indo-European thought did not reach ancient China, and Buddhism freed itself from the Indo-European metaphysical mold as it underwent a deep rethink during its introduction to China in the first half of the first millennium CE.

Jullien explains: ‘The Greeks thought from ‘cause’ and ‘principle’, the cause as primary and as a principle (arché – aitia, the two preliminary terms of Aristotle’s vocabulary). We enter into the ‘thing’, in other words, through the ‘cause’, causa, the former supporting the latter’s truth, and we ‘account’ … for any being whatever by something outside of itself – which is sufficient to disclose, at least in a symbolic way, this ex- of ex-plaining. ‘To know’ is to know the cause of things’, rerum cognoscere causas, as the Latin sententiously puts it in a formula that would dispel the mystery of the world by setting it out within this explanatory regime. God himself (this was already self-evident to Plato) is set forth as ‘first cause’, that to which one cannot go back and from which everything is linked and becomes ‘understandable’ or else, in the Phaedo, the ‘Idea’ is cause) (FBTL 2). This insight led Martin Heidegger’s to study the relation between “being” and “cause” in The Principle of Reason (Der Satz vom Grund), where he shows that the famous statement ‘nihil est sine ratione’, meaning ‘nothing is without a cause/reason’, is a syllogism because ‘what is’, (essential) ’being’ as such, had been defined as what has a cause/reason!

Causality ‘has so dominated European thought that we have not emerged from this framework and explanatory regime, which acts as a powerful lever, especially in the realm of physical knowledge, in a way that remained unsuspected until our modernity … This is to such an extent that our modernity, for one part, is really formed by how we try to extricate ourselves from this yoke and linkage – for what if these had no other justification than our ‘habit’ alone?To try to emancipate the mind from the great impetus of causality (as is already the case in physics), but especially in a way that meta-physics is destroyed by it, the latter having too credulously believed it was able to rest its edifice on this artifice (FBTL 2-3).

Inquiry into causality was not absent in ancient China but never became mainstream

Jullien writes: “Some Chinese thinkers from the end of antiquity (those who are called late Mohists) had also thought about causality and had even inscribed it at the head of their canon, but at the same time we note what an odd place they hold in the heart of Chinese tradition. They appear close to the Greeks in their interest in science, physics and optics, as well as in their need for definition and the rigour of refutation, and they never considered the tao, the ‘way’ … We can glimpse in their work the possibility of a form of thinking that Chinese tradition as a whole hasn’t developed … and so their texts have been transmitted to us only in fragments, having been recovered in China only at the dawn of the 20th century, rediscovered at the time that European thought was being encountered’ (FBTL 3).

Why then, did propensity, which didn’t seek to explain the world, prevail in China?

In fact, Jullien remarks,‘To think in terms not of causality but of propensity isn’t simply about leaving a regime of explanation for one of implication, or to pass from an external reason to one that is internal and in tune with immanence. More broadly, it also effects a shift from clarity through ‘cutting out’ (elements) and uncoupling (what is opposed), that of Being and its construction, into a logic that is both continuous and correlated and, as such, involves processes that are indefinitely interwoven. For it must be understood that the processural should be radically separated from what we have traditionally conceived as ‘becoming’, which is always understood within the shadow of Being and as its derivation or perdition.” Neither was Alfred N Whitehead’s Process and Reality, on which is based the Christian school of Process Theology, a return to what had been maligned as “becoming,” and centres where Process Theology is taught and practiced are thriving in China.

The mode of intelligence called upon to grasp propensity is discernment

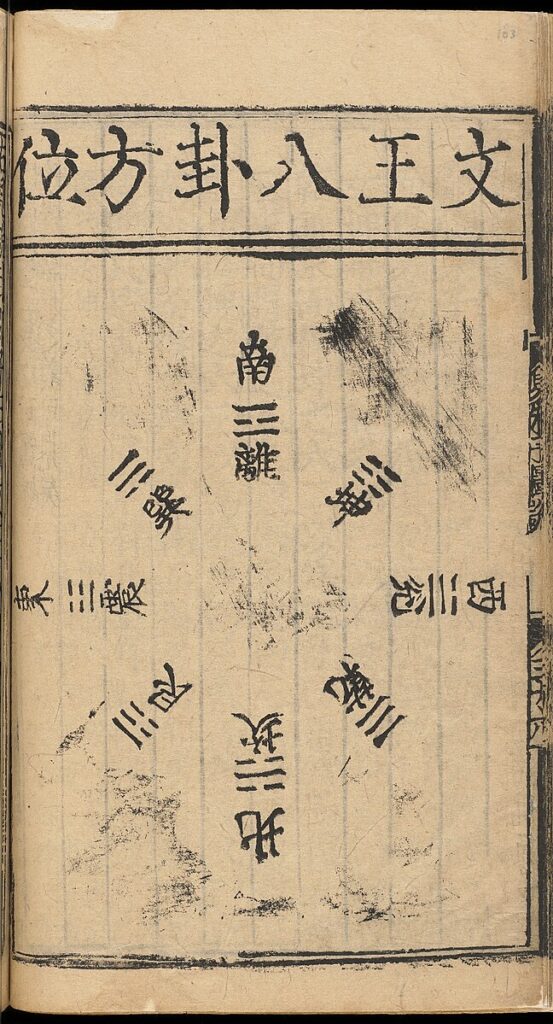

Here we come to the heart of the matter, one that most Westerners may find not so much difficult to “understand” as difficult to put into practice amidst the ups and downs of daily life. Jullien explains: ’The mode of intelligence called upon to grasp propensity isn’t ‘liaison’ (‘synthetic’: that of Kantian understanding), but let’s call it discernment (the frequent meaning of zhi)’ which he defines as follows:‘detecting a ‘priming’ of transformation in each thread or fibre of the situation (the ancient notion of ji in the Chinese Oracle of Changes). This means examining phases and stages rather than analysing states, so that the mutation to come is already perceived to be at work in the present aslinaments (the notion of xiang). This has been called ‘contextual intelligence,’ one that both branches out and is globalising, since one needs to detect how, at each instant, the configuration is propelled to shift in a certain way, and to do so in accordance with relations and variations that together form, by their effect of coupling what we call ‘situation’ – situation being the term we need to think afresh’ (FBTL 4). Hence it won’t be enough to focus on ‘the singular causation of an effect.’ We will need to apprehend the situation at hand intuitively and creatively, and ‘respond appropriately’ according to the specifics of the situation. Traditional Chinese scholarship describes this response as an alignment with the ‘intimations of the dao’, while Zen Buddhists say ‘All things coming and carrying out practice-enlightenment through the self is realization’. But these are still theoretical formulations of our relation to reality. The challenge here goes beyond understanding what we need to do. It is in actually doing it, and the Yijing (Book of Changes – Western Zhou period – 1000–750 BC) was designed to help practitioners ‘divine’ – in other words, ‘intuit’- to ‘detect how, at each instant, the configuration is propelled to shift in a certain way’ (FBTL 4).

Yetentering a logic of propensity means that the great European scenario of choice and its Freedom capsizes all at once, notwithstanding its sublimity’ (FBTL 4).

Jullien writes: ‘When it comes to ethics, the Greek question is that of the cause of my action … As soon as I do as the Greeks did and cut out and isolate a particular segment in the course of my behaviour, to which I assign a beginning and end and which I call an ‘action’ (praxis) that will subsequently only know succession through a plurality of addition (‘an’ action – ‘some’ actions), I cannot fail to question the origin and reason for such a unity of ‘action’ being constituted as an entity’ … The fact that the West became so attached to Freedom and made it its ideal reveals its anxiety about the capacity each of us has to be our own cause, independently of any external determination – in other words, to find our cause within our ‘self,’ to be causa sui, as Spinoza (in the first words of the Ethics) put it (FBTL 4).

On the other hand, Jullien argues, “as soon as we cease to think in terms of an isolatable, atomisable Being (or action), and start thinking in terms of a continuous (of what I thus call my conduct: ‘the course of the world’, ‘the course of conduct, tian-xing, ren-xing, is what the Chinese parallel says), the question can only become that of by what uninterrupted inclination, in what forms my incessant affective interaction with the world (xiang-gan), am I in the process of bending the value of my behaviour – am I raising or debasing it? … And the question that then arises is: how are we to deploy the slightest ‘priming’ of morality discovered within myself (like my reaction to what is ‘unbearable’, which I experience when suddenly coming across a misfortune that has happened to someone else, as in the Mencius) and “cultivate’ this inclination towards the good – in the same way as ‘water inclines downward’ – by favouring its conditioning? For it is when behaviour in its entirety is finally no more than the expression of this moral propensity, when virtue has become spontaneous and requires no further constraint and effort that one has attained ‘wisdom’ (FBTL 4-5).

This also applies when it comes to the understanding of history

Jullien quotes Fernand Braudel in On History, and Montesquieu in Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline, as having felt uneasy about “atomising history in events whose sequence will be sought out by successively finding each cause’ and called for the study of history in “its slow duration over a long period, and according to its driving force and in its ‘comprehensive propensity’ (named da shi by Wang Fuzhi), and further argues that “history isn’t formed from an indefinite teeming of causes that are impossible to inventory and that we retrace back to an arbitrary point, but from propensities that are always universal, that are considered on a more or less vast scale and that will increase and then reverse – or rather that, while they are growing and expanding, are already beginning discreetly to go into reverse … Salient events are themselves modifications; declared situations are never anything but transitions’ (FBTL 5).

To conclude, turning to the modern period, Jullien asks: ‘when did the ‘crisis’ in Europe begin?’ Just asking the question of when it began invites us to assume that it will come to an end as some point in the future. Yet, he says,

‘We get tired of this theatre of raising and lowering the curtain, of this facile and bland and reassuring imagery – the idea that, whatever the misfortune, there is light at the end of every ‘tunnel’. How are we unable so see this comprehensive propensity, according to which the modification, like a ground swell that the situation carries to all points, and above all from the West to the Far East? And then this inflexion will experience others that are already taking shape (FBTL 5-6).

Source:

François Jullien – From Being to Living, a Euro-Chinese lexicon of thought (2020-Original text De l’Être au Vivre 2015)