‘The good general is said to be one who is organising his troops like water accumulated at the top of a slope and in which a breach is suddenly opened – its passage will then carry everything in its path. Strategy, in other words, is simply a matter of knowing how to make good use of the situation by progressively bending it like a slope in developing its favourable propensity, and doing so in such a way that the effects rush down of their own accord and without having to be forced’ (François Jullien – From Being to Living p 9)

In From Being to Living, sinologist and hellenist François Jullien summarises his lifelong inquiry ‘through a series of oppositions in order to conceptualise what he calls the écarts (divergences) between European and Chinese ways of thinking’. Here he looks into the centrality of the self as subject in the West, and contrasts it with the focus on the ‘potential of the situation’ in China.

In European thought, from Augustine to Descartes, the self-subject is a point of departure

The centrality of the subject in the West is associated with Descartes’ well-known ‘cogito’. Jullien, however, sees it as going back to Saint Augustine, where it arose in connection with the Christian’s quest for interiority. He writes: ‘The first features of this ‘I think’, an insular cogito, appear in Saint Augustine, but it was Descartes who knew how to draw back the curtain and so brought into view what Hegel would call ‘the land of truth’ (FBTL 7). Unlike Saint Augustine, Descartes had set out to pass all he knew through a filter of systematic doubt, and concluded that the only thing he could be sure of was his own existence. He, at least, who had been doubting and thinking, had to be (that doubting and thinking being). Ego cogito, ergo sum. ‘I think therefore I am’. His goal was to establish a ground of certainty, that would put an end to all doubt, and on which Newton’s nascent scientific explorations could safely be carried out and lead to certainties.

Echoing the critiques of many scholars, notably among the thinkers of the Kyoto School, Jullien explains: ’the philosopher, who begins by ‘doubting’, discovering as he does so how uncertain and insecure his thought is, is obviously secondary compared with this initial ‘I’ on whose rock he has been able to roost in order to make a start.Or rather, this doubt is itself essential since it is from this ‘I’ of ‘I doubt’ alone that I discover that I cannot doubt, no matter how insistent my doubt may be’ (FBTL 7). ‘Yet’, he adds, for Descartes, ’this meant that from this moment he would no longer be entirely able to think but would only be able to do so within this fold of the subject. By means of this masterstroke, didn’t Descartes immediately and definitively cast out what was unthought? This notion of “folds” that, by restricting the field of what is thinkable, cuts the Sage off from the open field of thought, was the subject of Un Sage est sans Idée,’ a book that, to my knowledge, has not been translated into English. Ludwig Wittgenstein also said, likewise, that ‘The idea is already worn out, it’s no longer good for anything … It’s like silver paper, which can never be made smooth again once it’s been crumpled’ (1931).

Jullien notes that ‘the response has often been – even while it has been solemnly condemned – that what Descartes from the start radically cut out was the Other, definitively missing the joint origin of the You and the I, of the other and the subject, and so he isolated himself in his solipsism’. In Jullien’s eyes, ‘there is therefore something that in Europe we haven’t be able to recover, except by cobbling it together’ (FBTL 7). This is what Jullien has attempted to recover with the notion of ‘situation’ as an alternative to that of subject.

‘Subject or situation: this opposition is strangely illuminated quite differently in Chinese thought. Just think about what we call ‘landscape.’

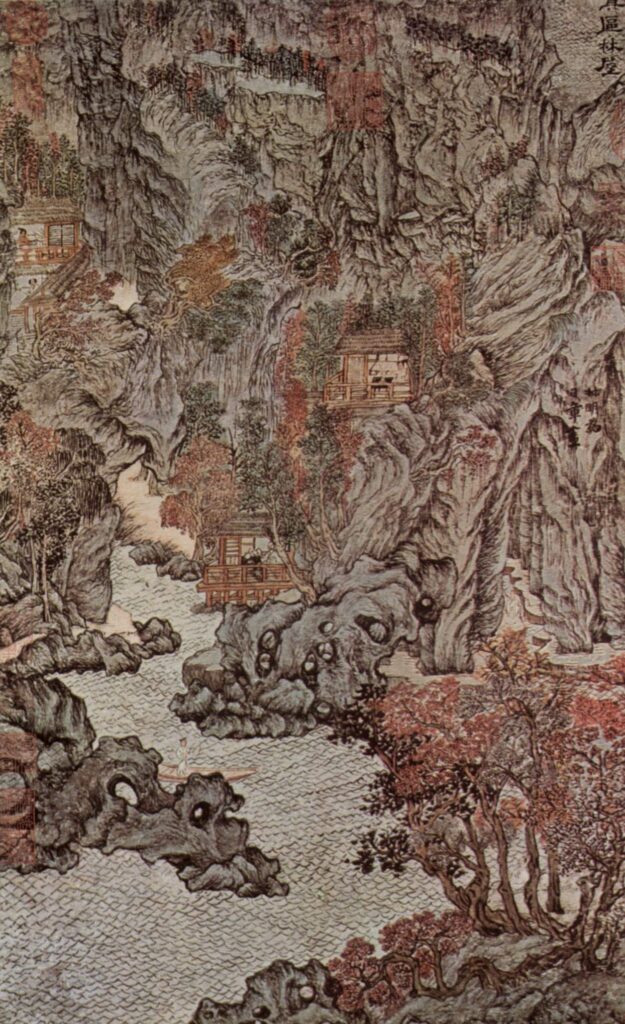

The notion of landscape was discovered during the Renaissance in Europe and defined as follows: ‘landscape is the ‘part of the land’, as the dictionary still says, ‘that nature presents to an observer’, who delineates it according to his perspective so that this horizon modifies itself in step with how he is positioned. The Subject, in other words, is in the presence of the landscape, which is external to him and remains autonomous; he is not implicated in it’. On the other hand, ‘China speaks not of landscape but of ‘mountain(s)-water(s)’, shanshui. At the same time, this is what extends towards the high (the mountain) and the low (water), towards what is motionless and remains unmoveable (the mountain) and what never stops billowing or flowing and what by nature is formless and married to the form of things (water), or towards what offers itself directly to sight (the mountain) and something whose rustling comes from various directions to the ear (water)’. While the Westerner just ‘ob-serves’, – the suffix “ob,” also found in ‘ob-ject’, carries the meaning of ‘towards, against’ the Chinese enters into a relationship with the natural world. Jullien is keen to add: ‘Another example we might note is what Chinese refers to as ‘wind-light’ feng-jing which indicates what on the one hand is constantly passing and animated but that we don’t see (the ‘wind’), and what on the other hand brings visibility and favours vitality (‘light’). In saying, or rather doing, this, Chinese thought-language always names a correlation of factors, entering into interaction and being constituted in polarity’ (FBTL 8).

For the Chinese, ‘the landscape is therefore not approached from the initiative of a subject, as the celebrated Cartesian beginning instituted it, but is conceived as an investment of capacities reciprocally at work, which is revealed to be both opposed and complementary, at whose heart ‘some’ subject is implicated’. Situation would thus designate in a preliminary way, this web of unlimited implications at whose heart each one is originally seized upon, whose configuration is outlined through various tensions and from which only by abstraction can one exempt oneself’ (FBTB 8-9). Jullien is here hinting at the Chinese naturalistic approach to nature itself, shaped by the qi surging from the Dao and flowing throughout what is here concretely referred to as ‘mountain(s)-water(s)’ (shanshui), and philosophically translated as ‘potential of situation’.

‘Shi’ as ‘situation’ is not simply a frame, or even a context, but also an active potential: strategy in the Art of War (Sun Tzu/ Sunzi)

Jullien continues: ‘This makes it possible for us to deploy such thought about the situation by going back to the Chinese term with which I started, taking apart the opposition between the static and the dynamic (also translated as ‘condition’ or ‘evolution’, shi), began in the Art of War of Ancient China by designating the potential to be taken advantage of in the situation. The divergence opened up at the outset is twofold here: on the one hand, the situation is immediately thought of as invested capacity; on the other hand, it is initially approached not in a speculative was but according to the use or function that follows from it … at the start of the Sunzi, the good general is said to be one who is organising his troops like water accumulated at the top of a slope and in which a breach is suddenly opened – its passage will then carry everything in its path. Strategy, in other words, is simply a matter of knowing how to make good use of the situation by progressively bending it like a slope in developing its favourable propensity, and doing so in such a way that the effects rush down of their own accord and without having to be forced’. For the Chinese, it is from the beginning a matter of making use of the situation. In Jullien’s words: ‘The strategist will no longer be someone who makes a plan in accordance with his objectives and projects it onto the situation, thus appealing to his ‘understanding’ in order to conceive of what should be and then to his will in order to make it accord with the facts. This ‘according’ can imply force – the ‘understanding’ and the ‘will’ being the two master faculties of the ‘subject of the European classical age. But the real strategist would be the one who knows how to discern, at once to detect and to unleash – directly from the situation itself in which he is engaged, and not in such a way that he would ideally reconfigure it in his mind – the favorable factors, the ‘contributing’ factors as they say. Following this and without others even noticing it, he will continually gain in propensity and turn the situation to his advantage’ (FBTL 9).

What may at first glance seem like a mere detail of strategy has had a profoundly significant impact on the contrasting roles of the subject and the natural world. Jullien explains: ‘This means that efficacy doesn’t strictly come from me, the subject who has conceived and willed the initiative, who has constructed a plan and then implemented it according to the time-honoured theory-practice relation from which Europe hasn’t extricated itself, but that, if I have been able to diagnose the potential in my favour by means of distributing factors, and then gradually to exploit them, then it advances directly from the situation itself. From this point, the situation … becomes a mine whose veins I’ll explore, a field of resources … on which I will learn to become a ‘surfer’ … I do this by identifying, ‘item by item, how favourable or unfavourable are the directions towards which the factors that conjoin in it are leaning (what direction offers the best relation between the prince and the general, or between the prince and the people, and so on; or which side has the best spies, and so on) … Therefore, instead of erecting a plan, I trace a diagram of factors and vectors at play, the lesson being that, before engaging in combat, I must tip over the potential of the situation onto my side: as a result, when I finally engage in the combat, I have already won; the enemy is already defeated’ ((FBTL 9-10).

Back to the European lexicon: circumstance is a feeble notion, it fragments the situation into infinite pieces, circumstances are inevitably a source of friction

Returning to the European lexicon, Jullien describes ‘situation’ as designating ‘the entirety of circumstances in which one finds oneself’ … But ‘circumstance(s)’ fragment the situation into infinite pieces due to its plural which slices up and juxtaposes (spatially, temporally, aspectually, etc.). Circumstance is therefore a feeble notion …‘Circum’-‘stance’ (in the same way péri-stasis in Greek; Um-stand in German): the circumstance is what ‘stands’ ‘around’. But around what, if it is not precisely the perspective of a sovereign Subject that predominates from the start?’ In Jullien’s view, circumstance is ‘a term that wrongly both stabilises and peripheralises, the subject being represented in it as an island against which the moving flow of circumstances will strike’. As centred on the subject while still outside of it, circumstances will be seen as occurring ‘unexpectedly against the plan that was put together ahead of time, and this means that it will gradually stumble and fall short.’ On the other hand, when I think of the ‘situation’ as potential, ‘the very evolution of the situation and its constantly renewing dynamism (something strongly expressed by the term shi) mean that, since no mind has been restricted by any projection, I can continue to take support as I incline this quality of situation to my advantage and gradually make use of it’ (FBTL 10). This refusal to be confined in one’s actions by a pre-established plan stems directly from the Chinese vision of ‘things’ in the process of self-actualisation, and explains today’s reluctance of the Chinese to sign business ‘contracts’. ‘Things’ change from day to day, and what is valid today may no longer be so tomorrow.

The battle is won even before combat has started. This is why China has not conceived any epics.

Jullien continues: ‘The victory is always simply the result of the potential of the situation in which one is engaged, or, as Sunzi tersely says about war, that it ‘doesn’t’ deviate (bù tè). This means, at the same time, that the battle is won even before combat has started; while the beaten troops are those ‘which seek victory only at the moment of combat’, hoping to snatch success. From this, it is finally inferred that the (true) good strategist is the one whose strategy is not even noticed and therefore whom no one thinks of ‘praising’. He has been so well prepared beforehand, in how to detect the favourable factors and continually making potential of the situation evolve to this advantage, that, when victory is achieved, everyone judges the success ‘easy’ and without merit, so much does it appear to have been brought about naturally by the situation and so to have been decided in advance. This ‘without merit’ is the great merit, which leaves the Subject of glory disappointed – we can appreciate why China has not conceived any epics’ (FBTL 11).

It is the grammar of our languages, in Europe, that arranges the circumstantial into compartments

Jullien believes that ‘it’s really the grammar of our languages, in Europe, its constricting system of rection [power or influence of one word over another word and prepositions, for instance in the use of a specific ‘case’] and above all its morphology of cases, which arranges the circumstantial into compartments, as the final complement’. This, he says, is ‘due to the situational inherent in the fact of existing. By the very fact of their formation, which also means that I am at the heart of a continual relation of interaction which, as such, constitutes ‘myself’ in response’ (FBTL 11). Japanese scholar Yuasa Yasuo also pointed out the role played by a rich syntax in Western phonetic languages, which allows them to be more precise compared to the Chinese language, which, lacking it, while also retaining ‘images’ in the ideographs, compelled readers to repeatedly glanced at the concrete context to make sense of what is said.

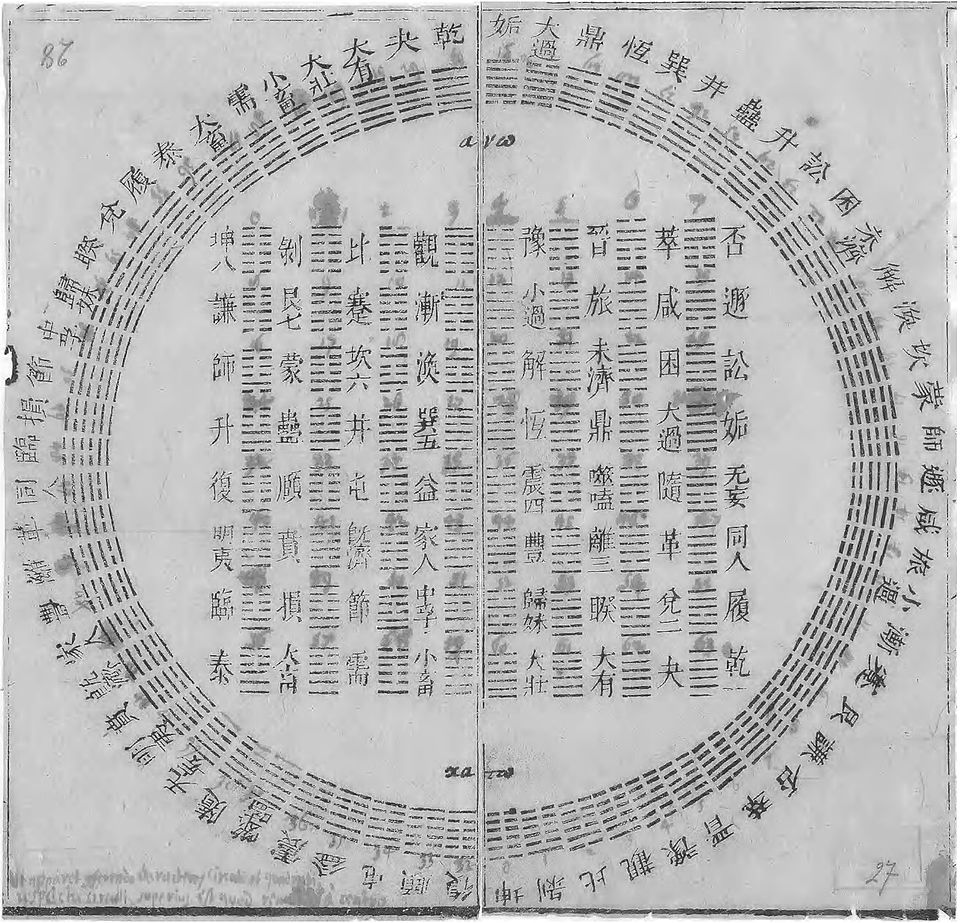

The I Ching (Yijing), which lacks logos or muthos, narrative or message, allowed Chinese to think in terms of actualisation and configuration, of propensity and the potential of situation, flow and energy, qi and not being and acting

Jullien holds that ‘Chinese thought is alone in having a clear strategic conception. It is because it thinks in terms of actualisation and configuration (the notion of xing), of propensity and the potential of situation (the notion of shi) and also (which is what lies behind these notions) in terms of flow and energy, the qi, and not of Being or Acting, which go together as a pair’ (FBTL 11). Referring to Clausewitz’s critique of the ‘failure of (European) thought in its thinking about war’, Jullien argues that the success of China is due to the fact that its thinking ‘isn’t constituted solely from an insular subject, but is one that involves an adversary from the outset’.It is because ‘China thinks in ‘terms of polarity’, that it found it ‘easy’ to think about war.’

More generally, ‘this also enables us to understand why the foundational book of Chinese culture should be the I Ching, the Book of Changes, a ‘book’ that lacks logos or muthos and is without a sustained discourse, as well as containing neither a narrative nor a message. From the beginning, it is composed of only two types of features (— and – -) that are full and broken, hard and malleable, yang or yin, representing the polarity at work. These are superimposed in figures which, transforming themselves into one another, symbolise so many situations that read themselves, feature after feature, in their evolution. This is to reveal – the ancient fruit of the mantic – how each situation is borne by its own nature to topple over, by nothing but the play of its factors (the only internal relation of these feature) in a ‘fortunate’ or ‘ill-fated’ way. In order to interfere in this play of energies, to get in phase with these figures, it will still be necessary to testify to what, opening up a breach in our vocabulary, I can’t find a better word to express this than receptivity (disponibilité), which begins to express a vacancy of the initiation and the will. This means that, just as the ontology of Being that serves as a basis of knowledge needs to be taken apart, so we will have to try to undo the ontology of the Subject that provides a basis for Freedom’ (FBTL 12).

Source:

François Jullien – From Being to Living, a Euro-Chinese lexicon of thought (2020-Original text De l’Être au Vivre 2015)