‘Sunzi concludes that it is always through a ‘surplus of indirection’ (yu qi) – that’s to say that I ultimately prevail over the other by being more indirect than he is. The essence of strategy therefore doesn’t consist in aligning a maximum of forces, either on the ground or on paper, any more than in relying on the courage of the troops or the general’s genius, but in – ‘indirectly (qi) – eluding, and outwitting the opposing resistance to such a point that it is forced to give way. I triumph, without striking further, simply due to the fact that the enemy’s defence has fallen’ (François Jullien – From Being to Living, p 36)

‘The encounter takes place facing one another, but victory is gained indirectly’

Jullien writes: ‘China … has been particularly at ease with thinking about strategy. This was not so much because it knew continual war at the end of antiquity, in the so-called era of ‘Warring States’ – when Arts of War (Sunzi, Sunbin, 5th-3rd centuries BCE) flourished – because war, as we are well aware, is everywhere, but because China developed a thought of polarity, in other words of opposed complementaries in interaction (the well-known yin and yang), which responds to the very essence of war and defines its condition between the adversary and oneself’. On the other hand, Europe, ‘thinking from an autonomous subject, has had great difficulty in considering strategy other than by resorting once again to creating a template (even if here it recognises its failure): the ‘war plan’ projected onto the situation and depending on the will to achieve victory’ (FBTL 36).

Sunzi (Sun Tzu), credited as the author of a widely read book translated as The Art of War, is said to have been a general, a military strategist and a philosopher who lived during the Warring States period (c. 475 – 221 BCE) though part of the book may have been added at a later time. His strategy can be summed up as ‘the encounter takes place facing one another’, but that ‘victory is gained indirectly’. Jullien explains: ‘Facing’ (zheng): frontally, openly, in an expected way and giving rise to confrontation; indirectly (qi): in an oblique and unexpected way, being where and when the adversary doesn’t expect it to be, to such an extent that he is helpless. Sunzi concludes that it is always through a ‘surplus of indirection’ (yu qi) – that’s to say that I ultimately prevail over the other by being more indirect than he is. The essence of strategy therefore doesn’t consist in aligning a maximum of forces, either on the ground or on paper, any more than in relying on the courage of the troops or the general’s genius, but in – ‘indirectly (qi) – eluding, and outwitting the opposing resistance to such a point that it is forced to give way. I triumph, without striking further, simply due to the fact that the enemy’s defence has fallen’.

Instead of drawing a ‘plan’ which might hamper the general’s ability to adapt to unexpected turns in the battle, Jullien adds, ‘he begins by establishing a diagram of the situation’s potential, concentrating on what is ‘firm’ and where the adversary has ‘gaps’, because it is when facing them that he will need to be continuously resolved, by remaining receptive and without getting bogged down in a restrained position.Or, rather, by knowing how to remain open to their incessant renewal through receptivity, he will be able to avoid sinking into a reifying determination that brings about inertia and reduces his energy, which is the worst strategy (FBTL 36-37).

Rather than mere opposites, frontality and indirectness are two phases of the same process

Drawing on Sun Bin, a later strategist of the Han Dynasty (202 BCE-220 CE) whose book has been translated as The Art of Warfare, Jullien points out that frontality and indirectness ’actually increase like two phases, or two states, of the same process. Frontality: each takes a position facing the other and can be located by him; indirectness: I lead the other to take a position on the ground and can control him, while – thanks to my reactivity – I remain ahead of any actualised configuration and, through this virtuality, keep myself alert. Against this, the other’s inertia leaves him defenceless because he doesn’t know what he must respond to. The adversary therefore finds himself destitute and reduced to passivity, simply because he doesn’t know what to expect or how to protect himself. Therefore, far from being one means among others, such an effect of ‘surprise’ is, in a crucial way, what by baffling (by dumbfounding, disarming and disorienting) brings out the weakness of the opponent and finally allows us to gain the upper hand through what until that point had remained covert and protected … not knowing how to reach me since he doesn’t know where I am – as I keep myself, without a definite position, in this alert state of reactivity – he cannot have a hold over me. From then on, everything that follows is an exploitation of the discountenance produced and has only consequential status’ (FBTL 37).

In Greece, single combats between heroes gave way to the face-to-face confrontation of phalanges

In contrast, Jullien tells us, in the 7th century BCE, Greece saw the ‘single combats between heroes like those celebrated by Homer, give way to … the direct confrontation of a pitched battle. A new structure was put in place – the phalanx – according to which two bodies of heavily armed and armoured hoplites, arranged in consecutive rows and marching together at the same pace, kept in step by the musicians’ auletes (flutes), advanced on one another in a close formation, with no possibility of flight. This face-to-face combat could only result in a heavy and destructive clash, for the only effort these men could make, on both sides, lay in the ‘thrust’ (othismos), so that the front row, which directly endured the enemy charge, found itself supported by the accumulated pressure of the rows behind them’ (FBTL 37).

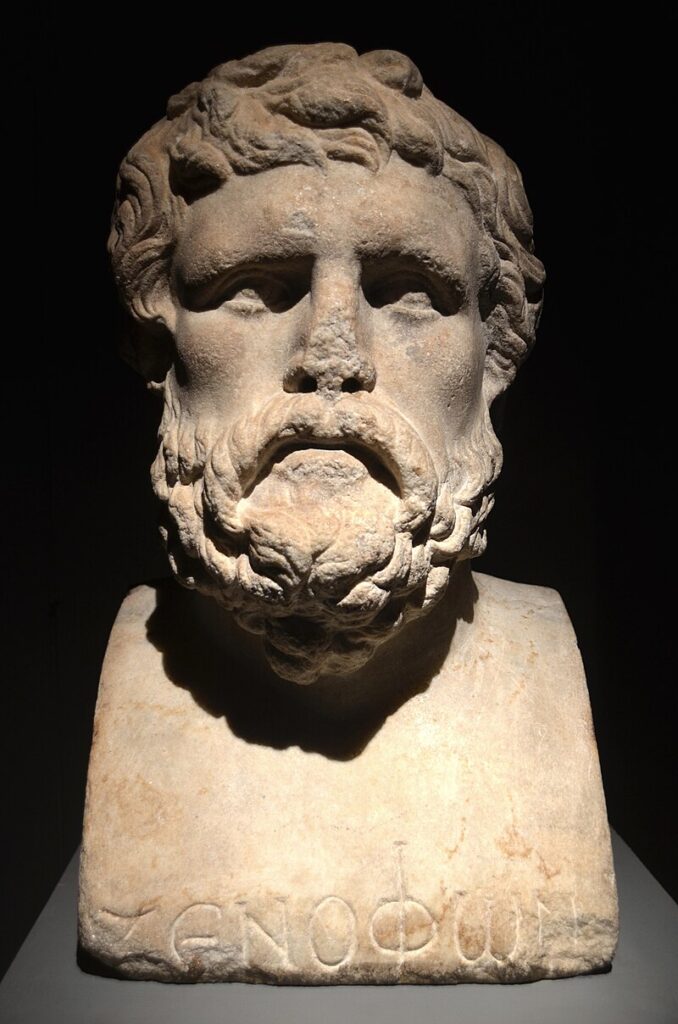

Pure carnage obviously resulted. Yet, there was a reason behind the choice of such a harsh approach to war: it cut down ‘the ravages of a prolonged war that spared neither goods nor families in the ‘all or nothing of pitched battle’, so gaining, by a brief and direct confrontation between those political bodies constituted as cities, a resolution that would be both as quick as possible and the least subject to doubt’. This also meant that ‘Any weapons that strike from afar or by surprise, such as arrows or javelins, [were] disparaged in favour of the lance, the face-to-face weapon by excellence’. Jullien quotes Polybius as saying that ‘The Greeks considered that it was only hand-to-hand battle at close quarters which was truly decisive and could validly determine a conflict’ (1925: XIII,3)’ and Xenophon that ‘Agesilaus decided that no matter what their number it is best to allow the two hostile forces to come together and, in case they wished to fight, to conduct the battle in regular fashion and in the open’ (1921:VI, 5)’ (FBTL 38).

This does not mean that the Greeks lacked a taste for stratagems: mètis

Jullien writes: ‘This model of direct confrontation – in other words, of frontality – does not mean that the ‘Greeks would have been unaware of the resource of subterfuge, or did not ‘show’ cunning’: we know they had a taste for stratagems’. This ‘cunning intelligence’ was referred to as mètis. Though important, as Marcel Detienne and Jean-Pierre Vernant have shown, (1978) mètis ‘isn’t the way … that the Greeks in the classical period deliberately chose to regulate their armed conflicts … Contrary to Chinese obliquity, mètis remained in the background of reason and moreover was clearly located only at the level of myth; the term would even vanish during the classical period. Repressed by speculative intelligence, it did not therefore become the object of a theory in Greece’ (FBTL 38). Mètis was at best a stopgap, an expedient.

The Greek form of confrontation was linked with the organisation of the City closely linked with the institution of democracy

What the contrast between Greek confrontation and Chinese obliquity in the context of their respective military strategies is not, however, valid only as a divergent art of war. It is best explicited as such, but it is also a contrast in the broader field of governance, and, as such, a foundation principle of their divergent mode of thinking and acting. Jullien writes that it‘appears that this Greek form of confrontation was all the more central in that it maintained a close link with the organisation of the City; it is actually contemporaneous with the rise of the City. Indeed, there would be a homology of structure between them: due to the uniformity of equipment, the equivalence of positions, even the identity of required conduct, the infantrymen of the phalange were reduced to the similarity of interchangeable elements that corresponded exactly with what they became as citizens in the egalitarian framework of their political life. The phalange therefore – and along with the logic of a frontal approach – appears to sum up a whole ‘choice’ of Greek culture as, by erecting opposing positions, it made the face-to-face encounter the best means by which to give the conflict shape, so as to settle it’ (FBTL 39).

For Jullien, then, there is an ‘equivalence’ between the face-to-face of phalanges on the battlefield and the ‘face-to-face discourses around which the City was organised. In fact this face-to-face is also ‘encountered again in the heart of the tribunal, the assembly and the theatre: in the theatrical agôn, the for and against of the Subject approached is defended in so many verses … In fact, whether it is theatrical, judicial or political, the debate is also played out as a weighing-up practised in one sense of another. And it is settled only according to the strength and number of arguments advanced on either side. Similarly, if there is a homology between the order of the phalange and that of the City, this isn’t just because the same participants appear on both sides (as citizens-soldiers), but above all from a structural standpoint: in both cases, the decision is won in the same way’ (FBTL 39). It comes out as the outcome of the confrontation between the strength of the arguments or oratory skills of two or more individuals or groups of individuals. Jullien then concludes, ‘this confrontation of discourses is closely linked with the institution of democracy: the question debated will be resolved by a weighing-up of an argued for and against – one has only to think about the importance that today’s political life places on televised ‘face-to-face’ debates. And don’t we see democracy slipping when the ‘for and against’ aren’t sufficiently distinguishable?Conversely, this also applies on the Chinese side: without authorising a declared opposition, isn’t the democratic ‘process’ still held in check today due to the fact that its cultural tradition grants a privilege to the indirect approach in the management of antagonistic relations? (FBTL 39-40)

From confrontation on the battlefield to democracy in the City to the Greek conception of logos to calculative thinking

Pursuing his inquiry into the extent to which the choice of confrontation between phalanges on the battlefield has shaped – as well as, to some extent reflected – the Greek mindset and mode of thinking, Jullien continues: ‘This face-to-face nature of discourse, just like the vote in which it results, arises from a singular logic whose principle we can perceive: while an isolated discourse is able to bring out an idea, the truth can only be expressed by two opposed discourses being bound as close together as possible through their confrontation. It is accepted that this practice of oratorical debates (the agôn logon) as we see it becoming established in the Greece of the fifth century, found its progenitor in Protagoras. ‘He was the first to say that there were two opposed discourses concerning everything. And our conception of logos would ensue in large part from this promotion of the confrontation of the word: if an opposing argument always exists to any argument that is already presented, then the art of discourse, which we know goes hand in hand with the arrival of our ‘reason’, would essentially consist in proposing opposing arguments to those introduced, so making them more convincing’ (FBTL 40).

Jullien further explains that the oratorical debate is based on an effort to keep ‘as close as possible to the opposing arguments’, through repeating ‘as far as possible the facts the adversary has put forward through his words and ideas, but arriving at conclusions that are the opposite of those proposed.’ He sees here an equivalence with the ‘‘isonomic’ [egalitarian] principle located in the structure of the phalanx … The rigour of the antilogy would therefore tend towards transforming all of the elements of the argumentation into comparable data, each aligned opposite one another and liable as much for addition as for subtraction – indeed, even being interchangeable with each other. Consequently, confrontation and calculation are the basis of this conflict of words, so much so that it is always through a surplus – but here it is the surplus of argument advanced and not concealed obliquity – that can claim to prevail. Hence, we appreciate that a single Greek term, logizesthai, means both to ‘consider’ and ‘to calculate’. This is also what philosophy has inherited (FBTL 40). In other words, to ‘reason’ is to ‘calculate.’ Rational thinking as based on Aristotle’s laws of reason is, as Heidegger also said, ‘calculative thinking.’

Rational thinking allowed Greece to ‘extricate itself from the sententiousness of wisdom’

Anyone familiar with the concise and peremptory utterances of the Chinese sages, said to encapsulate insights into the nature of the world, can only breathe a sigh of relief when listening to an argumentation, ‘proceeding by means of thesis and antithesis’ and its willingness to discuss instead of imposing its view of truth. ‘In philosophy’, Jullien writes, ‘this antilogy will become transformed into dialogue’. But can it be said to be a ‘direct’, in the sense of ‘unmediated’, or ‘spontaneous’ access to the truth? No, Jullien answers: ‘this didn’t prevent a certain fold from being taken in thought from the time of the Greeks. This is to think by means of opposing arguments in the most adapted way: we still teach children to philosophise through thesis and antithesis’. Though, he adds, ‘in Europe as well we have known how to proceed by using words obliquely, to express ourselves in roundabout ways’ (FBTL 41).

Nevertheless, Chinese intelligence has been far better at illuminating this art of the indirect that had remained in the shadows in Europe

Jullien continues: ‘As evidence, we could cite a military expression that has become a proverb: ‘kill the horse in order to strike at the knight’ – one which is still used in Chinese political life to register an indirect criticism of a chief through his subordinates … Another common expression, to which Mao Zedong again had recourse in his reflections on war as conducted by partisans, ‘make noise in the east so as to attack in the west’, applies still more readily to the order of discourse: on the one side, the whole volume occupied by explicit remarks that are only inserted to create a diversion. Also: ‘to point at the chicken in order to abuse the dog’ or ‘to point at the mulberry bush to abuse the cinnamon tree’. My remarks indicate one, but I’m aiming at the other, the one is merely the occasion for a detour – as such, it is ostensibly displayed – with a view to reach the other more effectively, but in secret’ (FBTL 41).

Just as confrontation on the battle field parallels the oratory joutes in the City, and the concept of logos as calculative thinking in Greece, the obliquity in the Chinese art of war echoes the practice of the verbal detour. Jullien says:‘instead of openly offering arguments to which the other will be able to respond, sinuous expression allows us to ‘evade’ any frontal attack that obliges us to justify ourselves …From the standpoint of verbal confrontation, too, the subtlety of the relation of the indirect opens the path to infinite games of manipulation that don’t get bogged down … this verbal strategy profits by always being situated in a purely suggestive – and inchoate – state of expression, for this barely outlined meaning, instead of locking us into a determined position that will then have to be defended, allows us to continue to evolve as we like since we remain master of the game. In this way, the adversary remains hanging on to the initiative of our barely started word, and is reduced to passivity’ (FBTL 42).

And this still holds true in modern China. Jullien quotes Liang Shiqiu, a Chinese literati at the beginning of the 20th century and himself a great translator of Shakespeare’, who, after a long stay in the West, described ‘this art of ‘striking from the side and attacking indirectly’, which he was so much better able to notice when he was back in China’: ‘It is stupid to call someone who steals from you a thief in order to reprimand him, or to call someone who robs you a bandit in order to reprimand him. When we want to reprimand someone, we first need to emphasise the art of emptiness and fullness, of the veil and the reflection. It is also advisable to suggest indirectly and to accentuate it indirectly, striking from the side and attacking laterally: having reached the crucial point, a single word is enough to finish it, and as they say you have the other ‘on their knees’ (The Fine Art of Reviling, Ma ren zhi yishu)’ (FBTL 42).

Whether at war or in a verbal encounter, it is best to ‘keep the adversary guessing’

‘If you directly accuse someone, there’s an end to it and there is nothing more to be said: there is nothing ‘beyond’ your word that can be deployed and might keep it agile. It is dead and inert, because it has been finished and its effect has been defused. The other knows what it is about and can refute you. But if you hint at what you might be thinking …, you lead him into unfolding of the word that puts the implicit to work and keeps him in suspense, making him anxious and uncomfortable … The same thing applies in military strategy, so that when you finally attack the adversary frontally, he is already defeated – just as you then barely have to act, so you barely have to speak. The efficacy of indirectness results from the process involved as it progressively reassigns the situation and doesn’t rely either on the word or the action’ (FBTL 42-43).

In the Zhuangzi, of course, this is the message conveyed by the story of Chi Hsing-tzu’s fighting cocks:

‘Chi Hsing-tzu trained fighting cocks for the King. After ten days the King asked

‘Are the cocks ready?’

‘Not yet. They go on strutting vaingloriously and working themselves into rages’.

After another ten days he asked again.

‘Not yet. They still start at shadows and echoes’.

After another ten days he asked again.

‘Good enough. Even if there’s a cock which crows, there’s no longer any change in them. From a distance they look like cocks of wood. The Power in them is complete. A strange cock would not dare to face them, it would turn and run’.

(Chuang-tzu – Chapter 19 – 135)

Sources:

François Jullien – From Being to Living, a Euro-Chinese lexicon of thought (2020-Original text De l’Être au Vivre 2015)

A C Graham – Chuang-Tzu, The Inner Chapters (1981)