“Once natural science and its image of the world had been established, the teleological conception of the natural world gave way to a mechanistic one, bringing a fundamental change in the relation between man and nature … As this intellectual process continued, the natural world assumed more and more the feature of a world cold and dead, governed by laws of mechanical necessity, completely indifferent to the fact of man. While it continues to be the world in which we live and is inseparably bound up with our existence, it is a world in which we find ourselves unable to live as man, in which our human mode of being is edged out of the picture or even obliterated” (Nishitani Keiji – Religion and Nothingness p 48).

Modern science is not just an aspect of knowledge: it is an autonomous discipline with its own method based on mathematics

Already in Essay 1 of Religion and Nothingness, Nishitani associates (modern) science, which had made it possible to control nature through technology, with the emergence of a view where humans see themselves as surrounded by “a cold, lifeless world,” as if “floating on a sea of dead matter. The life was snuffed out of nature … the living stream that flowed at the bottom of man and all things, and kept them bound together, dried up” (RN 11). He returns to the problem of science in Essays 2 and 3, where it is taken as the starting point of an inquiry which elucidates the impact of science to much deeper levels, concluding that “the emergence of the mechanization of human life and the transformation of man into a completely non-rational subject in pursuit of its desires are fundamentally bound up with one another” (RN 87).

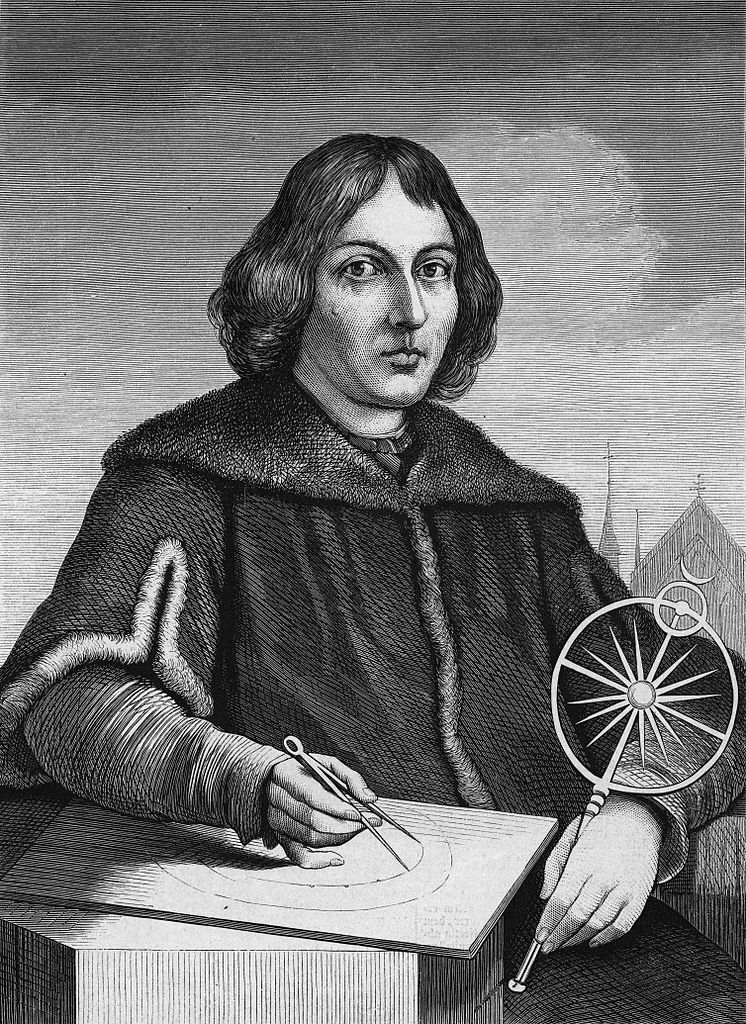

Modern science, as opposed to traditional science, which was simply regarded as an aspect of knowledge, is a relatively recent development, dating back to Copernicus’ publication of his treatise on Heavenly Spheres in 1543. This is the date widely regarded as marking the launch of the scientific revolution which led Kepler, Galileo, and Newton – supported by the philosophies of Bacon and Descartes – to establish science as an autonomous discipline, based on the primacy of external observation and the experimental method which requires that results be tested through experiments.

It may be useful to brush up on the particular characteristics of modern science before moving on to Nishitani’s “existential” analysis. As Cora-Jean E. Robinson sums it up, fundamental to the new scientific method was Descartes’s assertion of a duality “between the external realm of the body, i.e., the material domain of nature, and the internal realm of mind or soul.” Emphasis on external observation led to the assertion that “only what is external can be objective and real.” And, even in the external realm, “only those characteristics are regarded as primary [i.e., objectively real] that can be quantified and measured.” In other words, as Max Planck is reported to have stated, “what cannot be measured is not real.” The birth of modern science was not a painless one, since it contradicted the tenets of Christian belief, and what is referred to as the scientific revolution actually took over a century, with Copernicus’ life actually predating Descartes’s. “The scientific method called for a language which would lend itself to unambiguous agreement about the external characteristics of an object. That language was mathematics.” Also, “because it was internal, subjective and inherently unverifiable, the realm of mind was stripped of its reality, and reality was “divested of higher feelings or of sensations.” In fact, “human consciousness” itself has now “come to be regarded merely as … governed by the mechanical laws of nature” ( Robinson).

It is this science, based on mathematics, that had brought down the teleological worldview of reality, and led to Nietzsche’s declaration about the “Death of God.” It not only plunged human lives into utter meaninglessness, but also put them under the spell of a mechanistic worldview, which threatens to denaturalise nature and dehumanise humanity. “Once natural science and its image of the world had been established, the teleological conception of the natural world gave way to a mechanistic one, bringing a fundamental change in the relation between man and nature … As this intellectual process continued, the natural world assumed more and more the feature of a world cold and dead, governed by laws of mechanical necessity, completely indifferent to the fact of man. While it continues to be the world in which we live and is inseparably bound up with our existence, it is a world in which we find ourselves unable to live as man, in which our human mode of being is edged out of the picture or even obliterated” (RN 48).

Science’s “air of absoluteness”: “One cannot ‘get a word in’ from any point of view other than the scientific one.”

In Essay 3 of Religion and Nothingness – Nihility and Sunyata – Nishitani returns to the conflict between science and religion, and remarks that it is often said that, as long as each remains within its domain, they need not come into conflict. The problem with this assertion, he notes, is that “present-day science does not feel the need to concern itself with the limits of its own standpoint … Science … seems to regard its own scientific standpoint as a position of unquestionable truth from which it can assert itself in all directions. Hence the air of absoluteness that always accompanies scientific knowledge … The basic reason that science is able to regard its own standpoint as absolute truth rests in the complete objectivity of the laws of nature that afford scientific knowledge both its premises and its content. One cannot ‘get a word in’ … from any point of view other than the scientific one. Criticisms and corrections may only be brought to bear from the scientific standpoint itself” (RN 78).

Without challenging the value of complete objectivity as science’s absolute truth, Nishitani asks: “couldn’t there be two absolutes, according to the level at which reality is received, that is, whether it is seen as a natural law or as a concrete unfolding?” To explain his point he takes the example of a man tossing a crust of bread and a dog leaping up to catch it. From one angle, all ‘things/beings’ – the man, the dog, and the bread – and their movements are subject to physico-chemical laws. But from another, that of the concrete particularities of each of these things – the particular man, the particular dog, and the particular crust of bread – these do “exist in their own proper mode of being and their own proper form … and that as such they maintain a special relationship among themselves” (RN 79). There is, then, two ways of seeing the scene, as the manifestation of a natural law, or as the concrete interaction between the three particular “things/beings” actually taking place. One could therefore say that each angle is an absolute, and relate to each other as the two sides of a sheet of paper. The natural law has to be embodied in a particular set of things to be grasped, but, conversely, the man could not have thrown the bread to the dog, had not there been a set of natural laws making this possible.

Nishitani then remarks that “in the case of living organisms, the rule of law is encountered on the dimension of instinct … Instinctive behavior is the law of nature become manifest” (RN 80). In humans, however, natural laws do not become manifest as instincts, they must be apprehended through knowledge. The law of nature embodied in living things is grasped by the human intellect as a rational order which displays a purposive or teleological character. Even pre-civilised humans, when crafting tools, had to have some form of understanding of how nature operates. And it is even more so, of course, when it comes to technology. “Unlike simple instinct, technology implies an intellectual apprehension of these laws” (RN 81).

Continued on next page:

https://buddhism-thewayofemptiness.blog.nomagic.uk/crypto-nihilism-a-life-of-raw-and-impetuous-desire/

Sources:

Nishitani Keiji – Religion and Nothingness (serialised from 1961 onwards – English translation 1982)

Cora-Jean E. Robinson – “The Conflict of Science and Religion in Dynamic Sunyata,” in The Religious Philosophy of Nishitani Keiji, 101-113) ed. Taitetsu Unno (1989)