“In conceptual thinking, it is a self-evident tautology to say that finitude is finite; only in existential self-awareness, for the finite to grasp itself purely and simply as finite is for it to grasp its own finitude non-existentially, that is, ‘contemplatively‘ or, rather, ‘representationally’. Only from the standpoint of Existenz, can one ‘become aware of [one’s] own finitude as ‘infinitely finite‘” (Nishitani Keiji – Religion and Nothingness – Chapter 5).

Nihilism East and West

There are readers of Nishitani who feel uneasy about his original approach of philosophy and religion from the early “mood of nihility,” he also referred to as a “pre-philosophical nihilism” which had plagued his youth and early adulthood. Not having ever experienced such a deep sense of despair, some readers feel that Nishitani’s inquiry does not concern them. In Chapter 5 of Religion and Nothingness, Nishitani revisits the topic of nihilism, which he sees as an issue that also affected people in the ancient East even though it is today associated with the West, Nietzsche and the “death of God,” which, he says, “foreshadowed the ground-shattering collapse of European civilization as a whole.”

Even though “this sort of situation does not exist in the East, Nishitani says, “The awareness of the abyss of nihility found in nihilism … has been present in the East, particularly in India, since ancient times as a perennial and fundamental issue … The central role that the problem of birth and death has played in the East illustrates the presence of this awareness.”

“In Nietzsche, and in more contemporary figures like Heidegger … nihilism is dealt with on the horizon of the so-called ‘history of being’.” The East, on the other hand, has not only encountered nihilism early on in its history, but “has achieved a conversion from the standpoint of nihility to the standpoint of sunyata. Given this achievement, it seems a matter of course that we be driven to pursue as a modern question the relationship of the standpoint of sunyata to historicity: the modes in which historicity has appeared on that standpoint in the past and ought to appear there today.”

Samsara as “birth-and-death” and transmigration

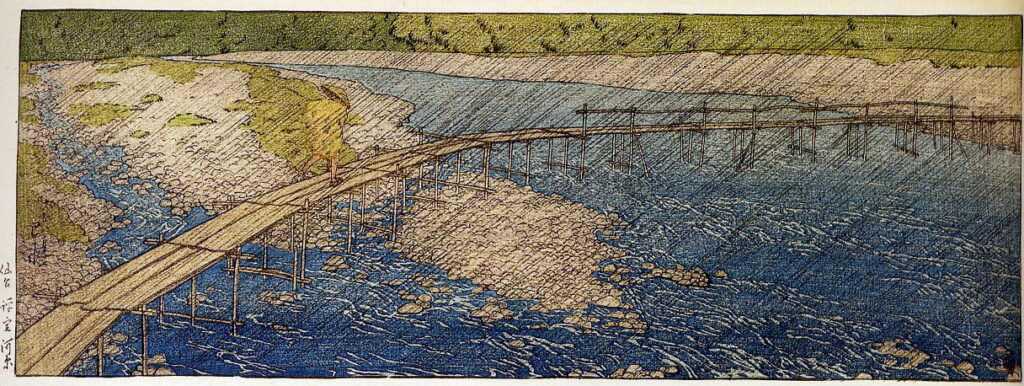

Nishitani writes: “The Sanskrit term “samsara” has been rendered as “birth-and-death” and also as “transmigration.” It refers to the world view according to which the forms of life and existence found among all that lives, including man – collectively called “sentient beings” – as well as the field of existence proper to each of these forms, are divided into “six ways” along which sentient beings are thought to migrate, alternating between birth and death like an endlessly rotating wheel.” In Heideggerian terms, it signifies the being-in-the world that is apparent in all sentient beings.” In Buddhism, this being-in-the-world is referred to as samsara and “is grasped in a keenly existential fashion. Buddhist teaching speaks, for instance, of the ‘sea of samsaric suffering’, likening the world, with all its six ways and its unending turnover from one form of existence to another, to an unfathomable sea and identifying the essential Form of beings made to roll with its restless motion as suffering.” The six ways Nishitani refers to here are the six realms of samsara, as depicted in the Buddhist Wheel of Life, which represents different states of existence within the cycle of rebirths, determined by karma: gods, demi-gods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts and hell.

In modern Europe too, the rise of nihilism is associated with “a Great Suffering (Leiden).” But, Nishitani writes: “Buddhism goes a step beyond the existential self-awareness of suffering to speak of a “universal suffering” where “All is suffering,” and to recognize in suffering a basic principle. It might not be wide of the mark to suggest that Buddhism’s explanation of suffering as one of its Four Noble Truths – the Truth about Suffering – be regarded as an advance beyond the existential awareness of suffering to an existential interpretation (in Heidegger’s sense) of being-in-the-world.”

So, while Heidegger thinks of suffering in terms of our existential awareness of suffering, Buddhism sees it as a universal principle of life which involves a “turnover of birth-and-death – that incessant becoming that is the essence of our being – occurs as a result of our own acts (the three karma of thought, word, and deed” … i.e., our voluntary actions of body and mind) and the ‘worldly passions’ that accompany them. Since our Dasein, determined by the karma of an unlimited past, in its turn determines the karma of an unlimited future, the essence of our present voluntary actions (karma) comes into perspective against the background of a causality of fate without end. ’Fate’, when ‘seen from the viewpoint of endless transmigration in the world of birth-and-death, … means fundamentally that everyone without exception reaps only the fruits of his own acts. Existence seen as suffering is able to clarify its true Form only by ‘taking hold of’ its own acts. One may explain this as a deeply existential prehension of being lying beneath the surface of this way of looking at birth and death in terms of samsara.”

The finitude of human existence is essentially an infinite finitude.

In Christianity and other theistic creeds, the hope for an eternal life of the soul is offered to the believer as a liberation from the finitude of lives ending in death. In Buddhism (and other religions native to India), the same principle of escape from finitude is formulated as an escape from the endless cycle of rebirths. In Nishitani’s words: “The finitude of man’s being-in-the world is here grasped as unbounded and unending in its essence. The finitude of human existence is essentially an infinite finitude. Now to be infinitely finite, or, in other words, for the finite to continue on infinitely, is ‘bad infinity’ (schlechte Unendlichkeit, as Hegel calls it), a concept that logic usually treats as a stepchild.”

Nishitani explains: “In conceptual thinking, it is a self-evident tautology to say that finitude is finite; only in existential self-awareness, for the finite to grasp itself purely and simply as finite is for it to grasp its own finitude nonexistentially, that is, ‘contemplatively’ or, rather, ‘representationally’. Only from the standpoint of Existenz, can one ‘become aware of [one’s] own finitude as ‘infinitely finite’.”

In more concrete terms, one could say that it has to do with the way we usually think of death as an event that will take place some time in the future in contrast to an “existential realisation of death.” Nishitani writes: “It is much the same with our ordinary way of considering death: on that day in the years ahead when I die, death will, along with me, cease to be. This representation of death is altogether different from what we spoke of before as existentially realizing the essence of death together with the essence of life from the midst of one’s own lived existence.” In Nishitani’s view, when one thinks of death in terms of the “end” of life that ends death at the same time, since one cannot die more than once, “access to a way beyond birth-and-death, passage to a field that has cast off birth-and-death, is blocked. It is not that a passageway beyond birth-and-death does not exist, but only that man bars himself from it and commits it to oblivion. (This is the true form of indifference to things religious).”

Transcendence-as-ecstasy

Nishitani continues: “the statement that the finite is finite, while quite valid in terms of conceptual thinking, is in error from an existential standpoint. It misses the essence of finitude, and because it is prehended from a standpoint that does not face up to existential finitude existentially, it fails truly to reveal finitude. From the standpoint of Existenz, not only the logic of discursive understanding but also the logic of speculative reason fundamentally entails such an omission. Indeed, it was just such an insight that called forth Kierkegaard’s confrontation with Hegel.”

This last remark, where Kierkegaard’s approach represents the existential standpoint, and Hegel’s the discursive/speculative understanding of reason, sums up Nishitani’s argument that seeks to rearticulate in the terms of modern western philosophy his distinction between the field of consciousness/reason/being, and the field of emptiness, which he is going to rename here as that of “ecstatic transcendence.”

Nishitani identifies a breakthrough of such a scope in the development of the phenomenological standpoint from Husserl to Heidegger. He writes: “Blossoming out of Husserl’s ‘intuition of essence’, it developed … in the ‘existential interpretation’ of Heidegger’s existential phenomenology. Within such a perspective, a ratio completely different in character from the ratio of logic comes to light.”

What Nishitani here calls a new sort of “ratio” “consists in man’s grasp of his own finitude on a dimension of transcendence – of “trans-descendence,” so to speak – that breaks through the standpoint of discursive understanding and speculative reason to the depth of his own existence. It is an awareness that the finitude of Dasein, as well as finite Dasein itself, becomes manifest from such a field of transcendence. It is, in other words, the ecstatic awareness of Dasein.”

Ecstatic Transcendence is also referred to as Trans-descendence

In the glossary included at the end of Religion and Nothingness, trans-descendence is described as follows: “Since the English word ‘transcendence’ seems to convey the image of ‘rising above’ whereas Nishitani wants to stress movement ‘to the ground’, in one section he amended the English to read ‘trans-descend’ at times. The first of the two characters in the compound … is used to express ‘going beyond’, or simply ‘beyond’, to express the ‘trans-‘ of the following expressions: transhistorical, transtemporal, transteleological, transpersonal, transconsciousness, trans-form, transnihilism, and over- (that is, “trans-“) man.” Trans-descendence was a better fit for a downward move toward the elemental while avoiding the word “immanence,” which is used in philosophical studies of Daoism, and which would have created a dualistic relationship with transcendence.

Nishitani writes: “The dimension of transcendence, or field of ecstasy, … is the field where the essence of finitude reaches awareness. It is the field where birth-and-death is seen as an endless ‘wheel of becoming’ (or samsara); or, we might say, the circular process of finite existence itself. To confront finitude existentially is to confirm through insight the essence of actual existence as a being-in-the world, and to do so directly underfoot of actual existence itself, on such a field of trans-descendence. In other words, for actual existence and its finitude to be confronted directly underfoot as what becomes manifest from a field that lies beyond even the dimension of reason is the revelation of the essence of finitude. The essence revealed in this way is entirely different in character from the so-called essence that is grasped conceptually on the dimension of reason. It can only be investigated existentially.”

“The man-centered point of view, the kind of outlook in which man sets himself at the center, has to be broken through”

Nishitani concludes: “We have two perspectives: one looks on the essence of birth-and-death as unending, the other as falling within a total scope that embraces man and the other species. In direct existential confrontation, they are fused together. If infinite finitude be said to constitute the temporal facet of the essence of birth-and-death in being-in-the-world, the total horizon can be called its spatial facet. The endless rotations of finitude, the circular process of finitude itself, is an endless pilgrimage of finite existence on a horizon embracing the forms of human existence and the existence of other species. The same correlation between temporality and spatiality is also seen in the way that man grasps the samsaric suffering of his being-in-the-world, against a background of ‘transmigration along the six ways’, as ‘universal suffering’. This Buddhist doctrine can also be seen as one expression of an existential investigation and existential interpretation of human existence.”

“Needless to say, in terms of its representational content, the notion of transmigration is “mythical” and can easily be criticized as prescientific fantasy”

Nishitani accepts that transmigration as commonly interpreted as the cycle of rebirths one undergoes over many kalpas, to which practice is meant to discontinue, belong to the realm of myth, which modernity argues should be discarded. Buddhism, in fact, has made inroads in the West, precisely because it had been demythologised to an extent Christianity has failed to be. “But,” Nishitani contends, “matters are not quite so simple. In general, scientific criticism against the mythical is quite correct to point out the limits of prelogical thinking involved in the representational content of myth. But it is quite incorrect to pass over the existential elements that compose the core of myth: the direct existential confrontation with being-in-world and the unique ratio this reveals, as we see these embodied in the mythico-religious aspects of human existence in prescientific societies. Here again, intellect is prone to throw out the baby with the bath: somehow the baby in the tub seems to elude the eye of intellect.” By discarding myth, modernity has lost the “existential confrontation with being-in-the-world” which is the very heart of religious and wisdom traditions, and thus the very foundation of our lives as humans.

Source:

Nishitani Keiji – Religion and Nothingness (serialised from 1961 onwards, English translation 1982)