“Impermanence is the Buddhahood”

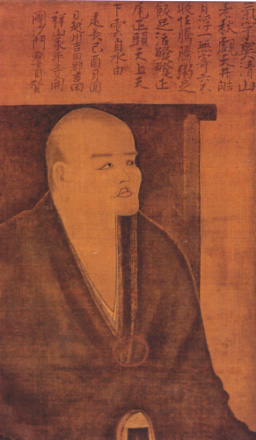

Dogen (1200-1253) was, with Keizan, the co-founder of the Soto Zen School, but it is only since the 17th century that his works have been seriously studied within the Soto tradition, and it has been barely a century since he is considered the most prominent Japanese philosopher in ancient Japan. In 1975, Hee-Jin Kim, a South Korean scholar who moved to the US, published Eihei Dogen: Mystical Realist, which I will use as a source for this page. Though Dogen studies in the West have grown by leaps and bounds since this early study, Kim’s work is still considered one of the best.

Among the many fascicles composing the Shobogenzo, “Uji” is one that still intrigues many Western scholars. “Uji” has been translated as “being-time,” “living time,” or “existence-time” (“U” meaning “being” or “existence,” and “ji” meaning “time”). Kim refers to it as “existence-time.” Parallels have been drawn by some scholars between Dogen’s Uji and Martin Heidegger’s concept of time in Being and Time. Kim focuses on the way Dogen remained faithful to the traditional concept of time in Buddhism, as he deepened its meaning from the standpoint of our practice, by presenting time through the lens of the self.

Impermanence

Born into one of the most powerful families in Japan at the very beginning of the Kamakura period, but brought up in the culturally over-refined ethos of the preceding Heian period, Dogen could have secured a brilliant career in politics, had he not lost his father at age two, and his mother, to whom he had felt very close, at age seven. His grief was profound. His mother had expressed the wish that he become a monk, and it is the path he chose when he entered the Tendai temple on Mt Hiei six years later. From the start, then, Dogen’s religious journey was marked by a keen sense of impermanence. Kim, however, notes that Dogen studied impermanence, and hence time, from a religious and philosophical standpoint, and not merely as a psychological mood oscillating between melancholy and fatalism.

Time in Buddhist thought

From early on Buddhist thinkers had tackled the problem of time as evidenced in the inclusion of impermanence (anicca) as one of the Three Marks of Existence, the other two being dukkha (suffering) and anatta (the absence of an abiding self). Dogen’s equation of time with things (dharmas), undoubtedly echoed the early insight that time had no independent existence, but was instead dependent on dharmas (things/events). In other words, things/events “did not move in time, but were time.” The idea that, of the three times – past, present, and future, only the present was real, which is one of the pillars of Dogen’s doctrine of time, had been a hot topic among the Sarvastisvadins, an influential school founded around the time of Asoka. It had caused the Sautrantikas, who upheld this view, to split from this school. The present was said to “contain” both past and future. As for the doctrine of the momentariness of all conditioned things, it seems that, though the idea may have been “floating” in particular Buddhist circles, its origin cannot be traced precisely to any text associated with the sixteen schools that had immediately followed the death of the Buddha, and one has had to wait until the 7th century for its systematic elucidation by the Mahayana thinker Dharmakirti.

These three characteristics of time – time as things, the present as “containing” the past and future, and the momentariness of all conditioned things – were developed, one could say, deepened, and integrated by Dogen with the more recent revolutionary Huayan idea of simultaneity whereby “all things and events of the universe originated, co-existed, and integrated simultaneously; they were co-related not only in terms of space but also time” (Hee-Jin Kim).

Another insight already in Buddhist thought had been “the mutual implication of space and time.” Whereas, in the development of the Buddhadharma over the centuries, the focus had been on the dimension of space, as encapsulated in “form is emptiness, emptiness is form,” with Dogen, the focus turned to the dimension of time, which Dogen found particularly helpful for Buddhist practitioners haunted by the thought of death. This is why scholars of Buddhism translate dharmas as “things/events.” This is also how, having anchored his quest in impermanence as a source of suffering, Dogen was to finally state that “Impermanence is the Buddhahood.”

Time doesn’t come and go

Dogen’s aim was to see time as it really is, in its “suchness” or “thusness,” beyond the way we see it on the screen of our reflective consciousness, where it has been overlaid by conceptual constructs. We normally see, and refer to, time as something that passes, flows, or comes and goes. We believe that the present is a narrow moment sandwiched between the past and the future. When we are bored, we try to “kill time.” When we are very busy, we say that we do not “have” time. This view of time is so ingrained in our minds that we never question it.

In line with the Buddhist tradition, Dogen states that time is not an entity that moves apart from things/events. In his characteristically concrete language, Dogen writes: “Standing on the peak of a high mountain is existence-time. Diving to the bottom of the deep ocean is existence-time. A deity with three heads and eight arms is existence-time. The Buddha [with the magnificent body] of one jo and six shaku is existence-time. A staff and a whisk are existence-time. A pillar and a lantern are existence-time. You and friends in the neighborhood are existence-time. The great earth and the empty sky are existence-time.”

The above is not, however, simply a metaphysical statement about the nature of reality, as Dogen adds: “You should examine the fact that all things and events of this entire universe are temporal particularities (jiji) … existence-time invariably means all times … All existence and all worlds are included in a temporal particularity. Just meditate on this for a moment: Is any existence or any world excluded from this present moment?” Writing as a religious thinker, rather than as a philosopher, Dogen concretizes the existence-time of all things/events as realized as my own existence-time. “The particular time of the magnificent Buddha [of today], too, is realized as nothing but my existence-time; seeming to be far away, it is the realized now (nikon).”

“Each realized now constitutes a unique whole of actuality” (Hee-Jin Kim)

As only the present really exists,whenever we speak about the world, though we constantly refers to a past that is believed to have left us, and a future that has not yet arrived, we in fact, in that very present moment, see the world as one single picture including what we have learned about the past, and whatever we now think the world will be in the future, and it is on the basis of this image that we think and live our lives. As we look at the world, the past and the future are included in “each realized now.” Moment to moment, the world changes, but with each moment, what we call the world includes the three times. In Dogen’s words: “The present time (konji) under consideration is each individual’s realized now (ninnin no nikon). Even though it makes you think of the past, present, and future, and tens of thousands of other times, they are the present time, the realized now. A person’s duty always lies in the present. At times the eyeballs might be regarded as the present time; at other times, the nostrils are the present time.”

Momentariness – “Everything perishes as soon as it arises”

Dogen introduces the ancient Buddhist idea of the momentariness of time through the Buddhist saying that “Everything perishes as soon as it arises.” As our human bodies are renewed moment to moment by the five skandhas that are themselves subject to changing conditions, “life arises and perishes instantaneously moment to moment and does not abide at all” (Dogen). This amounts to a denial of duration.

Dogen further analyses momentariness as follows: “When firewood becomes ash, it can no longer revert to firewood. Hence, you should not regard ash as following and firewood as preceding [as if they formed a continuous process of a self-identical entity]. Take note that firewood abides in its own Dharma-position (hoi), having both before and after … Just as firewood does not revert to firewood again after having been burnt to ash, so death is not transformed into life after the individual is dead. Thus, do not hold that life becomes death; this is an authoritative teaching of the Buddha-dharma … Life is a position of total time, death is a position of total time as well. They are like winter and spring. We do not think that winter turns to spring or that spring turns to summer.”

Asserting, as Dogen does here, that there is a direction of time – ash cannot turn back into firewood, death cannot turn back into life – adding that each is a “Dharma position,” could lead us to see time as “flowing” unidirectionally from the past to the future. A better grasp of what appears to be a “flow” would be to take each moment as a frame in a film: one sees the actors moving on the screen without any gap between their successive positions, yet it is possible to isolate each frame of the film, as the illusion of movement is created by the rapid succession of frames.

Dharma-position – “Those who know a speck of dust know the entire universe” (Dogen)

Dogen’s concept of Dharma-position needs to be clarified. Given that both past and present are contained in each “realized now,” a Dharma-position is what Kim referred to as the “unique whole of actuality” embraced as each “realized now.” A Dharma-position includes the biological, psychological, moral, philosophical, and religious aspects of our view of the world as organised in a coherent and meaningful whole.

The notion of Dharma-position is associated with that of “exertion (gujin),” an expression Dogen uses frequently, and which he describes as follows: “Those who know a speck of dust know the entire universe; those who penetrate a single dharma penetrate all dharmas. If you do not penetrate all dharmas, you do not penetrate a dharma … While you study a speck of dust, you study the entire universe without fail.”

Dogen further explains: “Life is, for example, like sailing in a boat. Although we set a sail, steer our course, and pole the boat along, the boat carries us and we do not exist apart from the boat. By sailing in the boat, we make the boat what it is … I make life what it is; life makes me what I am. In riding the boat, one’s body and mind, and the self and the world are together the dynamic function of the boat (fune no kikan). The entire earth and the whole empty sky are in company with the boat’s vigorous exertion. Such is the I that is life, the life that is I.”

The above suggests a sort of interaction between the boat and us whereby as the boat carries us, we make the boat what it is, and this interaction could be seen as an interbeing in action. Francis Cook described “exertion” as follows: “From the angle of the person who experiences the situation, [gujin] means that one identifies with it utterly. Looked at from the standpoint of the situation itself, the situation is totally manifested or exerted without obstruction.” “Without obstruction” refers to our letting go of all ego-based likes and dislikes, so that we can wholeheartedly embrace the present moment, and totally identify with the situation, so that it is “exerted,” that is, allowed to manifest as it is.

This is what Dogen meant in the second sentence of his often-quoted formula: “To carry yourself forward and experience myriad things is delusion. That myriad things come forth and experience themselves is awakening” (translation by Tanahashi Kazuaki).

When we have silenced our ego, and overcome any attempt at imposing our concepts on things/events, “a mountain mountains a mountain, thereby a mountain realizes itself.” As Heidegger would say, “the world worlds.” The world is allowed to manifest as a “verb,” an activity – rather than a collection of substantial objects – which I interact with, receiving and giving at the same time.

“The past, present, and future, in an epochal whole are … realized simultaneously in the manner of mutual identity and mutual penetration” (Hee-Jin Kim)

The association of the notion of Dharma-position with that of the activity of exertion does not, however, mean that each present is, as it were, an instance in a linear view of time, a view that would suggest a chronology and a duration within that chronology. Instead Dogen, following the Huayan principle of “simultaneous completion and co-existence,” asserts that “all things and events of the universe originated, co-existed, and integrated simultaneously; they were co-related not only in terms of space but also time. Hence, the fundamental idea was simultaneity” (Hee-Jin Kim).

The Huayan school can be described as having expanded the doctrine of co-dependent origination into a holographic worldview of “mutual identity and interpenetration of all phenomena.” Francis Cook described it more technically as a relationship of “simultaneous mutual identity and mutual intercausality (or interdependence)” among all things in the universe. Mutual identity refers to the co-existing of opposites, “mutual penetration refers to the simultaneous origination of all things and events that interpenetrated one another” (Hee-Jin Kim). “This simultaneity, Kim adds, “was experienced most concretely and vividly in the present moment of a single thought of one’s lived experience.”

In simple terms, when we look at the world, what is past does not arise first, followed by the present and then the future. All aspects of the world arise in our consciousness simultaneously in the present moment as the “realized now,” which Kim has called “a unique whole of actuality.” This is also what Alfred North Whitehead has called “an epochal whole.” Kim writes: “The structure of the realized now is such that the past, present, and future, in an epochal whole (to use Whitehead’s term here for convenience’s sake), are not arranged in a linear fashion but realized simultaneously in the manner of mutual identity and mutual penetration.”

“Dynamism (kyoryaku) is the characteristic of time.”

Dogen’s focus on the “epochal whole” where past, present and future arise simultaneously in the “realized now,” was meant to undermine any remaining notion of time as flow. Now, however, he can feel free to let us know where a dynamism we can call “flow” belongs: it is in what Dogen calls “kyoryaku.”

Dogen wrote: “Existence-time has the characteristic of passage (kyoryaku): it passes from today to tomorrow, from today to yesterday, from yesterday to today, from today to today, and from tomorrow to tomorrow [in the experience of my realized now]. Dynamism (kyoryaku) is the characteristic of time.”

Kim explains further: “Temporal passage (kyoryaku), in this view, was not so much a succession or contiguity of inter-epochal wholes, as it was the dynamic experience of an intra-epochal whole of the realized now, in which the selective memory of the past and the projected anticipation of the future were subjectively appropriated in a unique manner. In brief, continuity in Dogen’s context meant dynamism. (In this sense alone, Dogen allowed for the notion of “flow” in time.)”

Temporal passage (kyoryaku) is not to be understood as the passage from one thing to another, like a storm passing from one point to another, but instead as a dynamism within all things that allows them to realise themselves. “The world is neither motionless and changeless nor without advance and retreat: it is temporal passage. Passage is, then, like spring. Myriad events take place in the spring and they are called passage … the passage of spring always passes through spring itself … it is the dynamism of spring” (Dogen).

“Dependent origination is activity, because activity does not originate dependently” (Dogen)

Dogen writes: “The sun, the moon, and the stars exist by virtue of such creative activities. The earth and the empty sky exist because of activities; so are the four elements and the five skandhas … It should be examined and understood thoroughly that dependent origination is activity, because activity does not originate dependently.”

Kim comments that “Dogen went beyond the conventional way of thinking in Buddhist philosophy by asserting that activity was more primitive than dependent origination. This was not to deny the significance of the latter, but to probe the nature of its conditions and causes – that is, to probe all things of the universe – in order to deepen our understanding of them as activities.”

In temporal passage Dogen sees the arising of all things through co-dependent origination as the result of a dynamic process whereby the One actualizes itself as the many things/events through our conscious self. Dogen says: “Unless my self puts forth the utmost exertion and lives time now, not a single thing will be realized, nor will it ever live time.” This prompts Kim to comment: “Herein lay Dogen’s existential solution to the problem of one and many.”

So, what is existence-time?

With his concept of existence-time, Dogen presented time in terms of three characteristics. First, he deepened the traditional Buddhist view of time as dharmas: things/events do not move in time but are time.

Second, Dogen’s concept of time fully incorporated into itself the self and the world. Whereas Buddhist practice has generally been formulated in terms of space (as in “form is emptiness”), Dogen is inviting us to formulate it in terms of time. As we silence our ego-centred habits, we “exert” the things/events, and allow them to realise themselves as what they truly are.

Third, Dogen explained how this is achieved by the intra-subjective activity of the “realized now,” which brings together past, present, and future into the single thought of the present moment, where they are integrated into a “unique whole of actuality,” or “epochal whole.” The “exertion” is carried out through co-dependent origination now conceived as an “activity.” It is not ultimately seen as “our” exertion, but rather the activity of reality that realises itself through our consciousness into the things/events we see, without being “obstructed” by our attachments.

Kim concludes the section on existence-time with the words: “Time is activity and activity is time. The realized now consists, not in a static timelessness that enables us to accept the given reality as it is, but rather in a dynamic that involves us intimately in time and hence transforms our deeds, speech, and thought. The realization of activity signals this element of transformation. But this element is in turn inseparably connected with the perpetuation of the Way, comparable to the forward revolution of the wheel of Dharma – it advances in history, but is an advance in enlightenment.”

Dogen’s elucidation of time amounts to a new positive revalorisation of the many, and time/impermanence in the context of an East Asian world that sees the spiritual life as “cultivation” for a life in this world. Dogen writes: “Impermanence is the Buddhahood … The impermanence of grass, trees, forests is verily the Buddhahood. The impermanence of the person’s body and mind is verily the Buddhahood. The impermanence of the (land) country and scenery is verily the Buddhahood … Buddhahood is time. He who wants to know Buddhahood may know it by knowing time as it is revealed to us” (Bussho section of Shobogenzo).

Kyoto School philosopher Nishitani Keiji, who is said to have been deeply influenced by Dogen, describes this notion of “exertion” as the “real self-awareness or self-realization of reality,” as follows:

“By the “self-awareness of reality” I mean both our becoming aware of reality and, at the same time, the reality realizing itself in our awareness. The English word “realize,” with its twofold meaning of “actualize” and “understand” is particularly well suited to what I have in mind here, although I am told that its sense of “understand” does not necessarily connote the sense of reality coming to actualization in us. Be that as it may, I am using the word to indicate that our ability to perceive reality means that reality realizes (actualizes) itself in us; that this in turn is the only way that we can realize (appropriate through understanding) the fact that reality is so realizing itself in us; and that in so doing the self-realization of reality itself takes place.” Nishitani also writes: “What I am speaking of is not theoretical knowledge but a real appropriation.”

Sources

Hee-Jin Kim – Eihei Dogen: Mystical Realist (1975)

Francis H. Cook – How to Raise an Ox: Zen Practice as Taught in Master Dogen’s Shobogenzo (2002)

Francis H. Cook – Hua-yen Buddhism – The Jewel Net of Indra (1977)

Nishitani Keiji – Religion and Nothingness (English translation 1982)