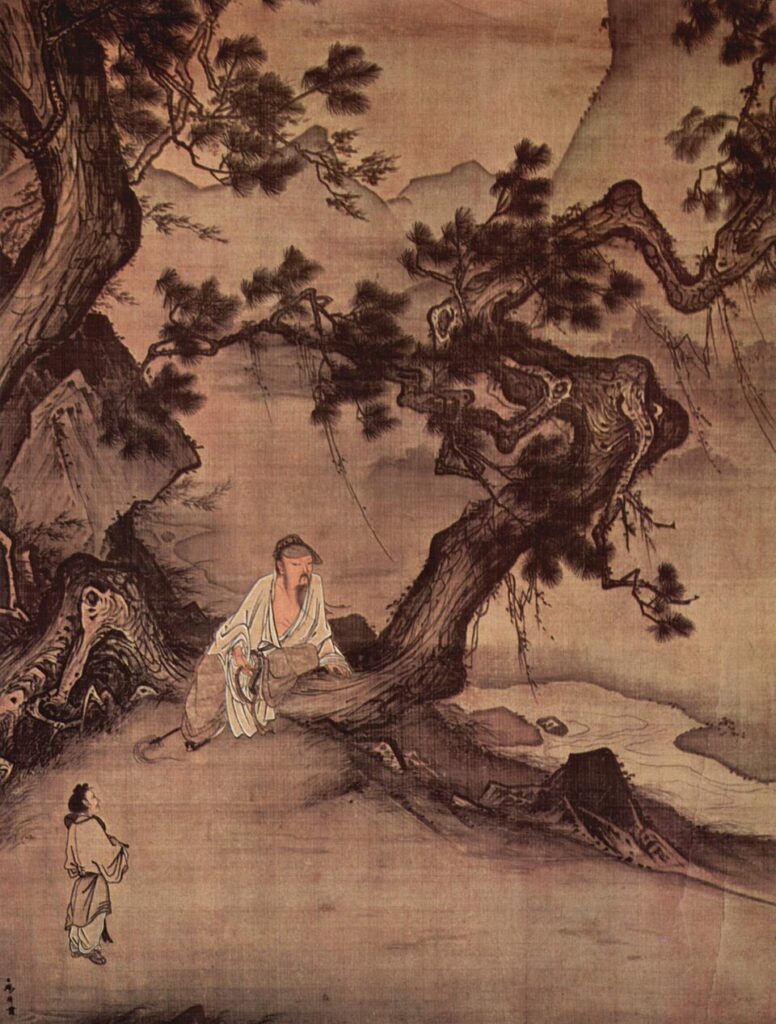

Fazang – Japanese print -13th century – Todaiji, Nara

The Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana is attributed to Asvaghosa, an Indian Buddhist philosopher in the 2nd century CE, but scholars agree that it was composed in China in the 6th century CE

The Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana is traditionally attributed to Asvaghosa (c. 80–c. 120 CE), an Indian Buddhist philosopher. As no Sanskrit version of the text has been found, scholars now generally agree that it is an apocryphon composed in China in the 6th century, most likely by the monk considered to be its translator, believed to be Paramartha. In his introduction to the text, Yoshito S. Hakeda, states that “the fact that Asvaghosa’s name was attached to the text undoubtedly has had much to do with its popularity. He is known in Chinese as Maming or “Horse-neighing,” a literal translation of Asvaghosa; the name derives from the saying that his poems were so moving that when they were recited even the horses neighed in response. But, Hakeda adds: “One thing is clear, however, from evidence within the text itself, that it was not written by the Asvaghosa who lived in the first or second century C.E. and who has been honored as the first Sanskrit poet of the kavya or court poetry style, the earliest dramatic writer in India whose work has survived, and the distinguished predecessor of the great Kalidasa. Only three works are agreed upon with certainty by Indologists as having been written by this Asvaghosa … No evidence of Mahayana thought can be detected in any of these works; they deal strictly with the doctrines of the Theravada or Hinayana branch of Buddhism.” No one at the time, however, doubted that Asvaghosa was the author of the text.

As for Paramartha (499–569), the alleged translator of the text, Hakeda regards him as “equally eminent,” with “translations credited to his name running to over 300 juan (fascicles) in volume.” Paramartha was a monk from Ujjayini (today’s Ujjain) in West India “who came to China over the southern sea route in 546.” A catalogue of Buddhist texts lists the “translation” of the Awakening as having been completed in 550, which would have been only four years after Paramartha’s arrival in China. Another source indicates that the local ruler in Paramartha’s birthplace was a fervent supporter of Yogacara and sponsored his travels to spread Buddhist teachings. In China, Paramartha was associated with the Shelun school, a branch of Yogacara whose teachings differed from those of Xuanzang, who later founded the Chinese school of Yogacara (known as the School of Consciousness Only) in the 7th century, a century after Paramartha composed The Awakening. Xuanzang viewed the mind as impure and in need of complete transformation, while the Shelun school perceived it as inherently pure; liberation, therefore, consisted of recovering this intrinsic purity, which Paramartha advocates in The Awakening. Admittedly, Paramartha wrote in 550, and Xuanzang (602-664) traveled to India in 630, returning in 645 with the texts that enabled him to establish the Yogacara school in China. Thus, in The Awakening, we observe an integration between an interpretation of Yogacara, brought directly from India by an Indian monk, and the Tathagata-garbha, or doctrine of Buddha-nature. Although writing in Chinese, Paramartha, of Indian origin, presented his text in a typically Indian manner: with numerous numbered lists and abstract, sutra-like metaphysical terminology, which ultimately led to the failure of the Madhyamaka and Yogacara schools established in China. The average Chinese Buddhist practitioner had to be instructed through concrete experience.

The work is a comprehensive summary of the essentials of Mahayana Buddhism

Hakeda describes the Awakening as follows: “The work is a comprehensive summary of the essentials of Mahayana Buddhism, the product of a mind extraordinarily apt at synthesis. It begins with an examination of the nature of the absolute or enlightenment and of the phenomenal world or nonenlightenment, and discusses the relationships that exist between them; from there it passes on to the question of how human beings may transcend their finite state and participate in the life of the infinite while still remaining in the midst of the phenomenal order; it concludes with a discussion of particular practices and techniques that will aid the believer in the awakening and growth of his faith. In spite of its deep concern with philosophical concepts and definitions, therefore, it is essentially a religious work, a map drawn by a man of unshakable faith that will guide the believer to the peak of understanding. But the map and the peak are only provisional symbols, skillful and expedient ways employed to bring people to enlightenment. The text and all the arguments in it exist not for their own sake, but for the sake of this objective alone. The treatise is, indeed, a true classic of Mahayana Buddhism.” In other words, it is not a philosophical text in the restricted sense of an inquiry into the metaphysical nature of the cosmos. It, instead, falls in the category of upaya (skilfull means), a narrative composed for the purpose of helping practitioners gain the transformative realisation of enlightenment. In addition, “difficulties arise from the nature of the Chinese language, which, though highly symbolic and suggestive, lacks the logical precision of Sanskrit. The fact that we have no Sanskrit or Tibetan version of the text to assist our understanding of the Chinese makes the problem of interpretation doubly difficult.”

How could “the originally pure, enlightened mind intrinsic to all sentient beings, conceptualized as the ‘womb’ or ‘embryo’ of Buddhahood” also be the source of illusion and suffering?

As they developed in response to the Madhyamaka school, the Tathagata-garbha and Yogacara schools were less concerned with competing with Madhyamaka than with strengthening its doctrine of sunyata (emptiness) which had become its signature concept. While it equated sunyata with co-dependent origination and the Middle Path, it, in the words of Peter Harvey, had resulted in “phenomena supported by nothing but other unsupported phenomena,” and had been the target of accusations of nihilism.

Both the Tathagata-garbha Sutra and the Sutra on the Lion’s Roar of Queen Srimala, regarded as the most important texts of the Tathagata-garbha school, were composed in the Andhra region (in South India) between 200 and 350 CE shortly after Nagarjuna’s lifetime (150-250). On the other hand, Asanga and Vasubandhu, who founded the Yogacara school, were born and lived in Gandhara in the 4th century. But, already in India, three centuries before the composition of The Awakening of Faith, the Yogacara and Tathagata-garbha schools had joined forces to deepen the tradition of Indian Mahayana Buddhism.

Harvey writes: “The concept of a seed potential or of a womb-like container in which Buddhahood grows is … often encountered in Vijnanavadin [Yogacara] texts, such as the Lankavatara Sutra, Samdhinirmocana Sutra, and the Mahayanasamgraha is often assimilated to the concept of the alaya-vijnana.”It is in fact explicitly said in the Lankavatara Sutra, compiled between the 4th and 5th centuries CE, that“the alaya-vijnana is also known as the Tathagata-garbha”(Peter Harvey). This sutra had been promptly translated into Chinese around 420 CE, possibly a century before the publication of the Awakening of Faith.

In the Yogacara’s elaborate doctrine of consciousness, an eighth layer of consciousness had been added to the original system of seven “active” consciousnesses found in the Abhidharma. This eighth deeper layer of consciousness was called alaya-consciousness, that is, the storehouse or “receptacle-consciousness” and was described as storing karmic “seeds,” “not only the seeds of defilement and ignorance, but the seeds of purification and wisdom as well” (Francis Cook). The process is not unlike that of genetic material passed on at birth, which the West sees as a “code,” rather than a substance. In the case of the karmic seeds, however, the view is that of a dynamic flow of life energy, and the image of the seeds represents a potential for growth, activity, movement, change, i.e., life itself.

The difference between the two schools was best viewed as a matter of emphasis. Yogacara focused on the “mechanics” of consciousness, showing how the alaya projects karmically defiled images into the “things” we see in such a way that they appear to exist outside us, independent of us. It is what is referred to as “the construction of the unreal.” Whereas we usually believe our consciousness to mirror things existing in a world perceived as external to us, this is not so. Karmic seeds arising from the alaya-consciousness cause us to “edit highlights” in our field of perception, i.e., select what is of interest to us, or threatens us or disgusts us, thereby distorting our view of the world. We do not realise that what we see is not the world outside, but our reorganisation of it, manufactured in the alaya-consciousness. In India, it had been believed that the extirpation of the defiled karmic seeds was a process that required many lifetimes.

The Tathagata-garbha writers, on the other hand, emphasised the original purity of the mind, the “brightly shining citta,”a concept reflecting the benevolent qualities of the nature of dharma, which is also found in the Yogacara, the Madhyamaka and the Prajnaparamita literature, but which is givena more prominent position in the Tathagata-garbha teachings.

Before approaching the text, it is worth noting that the word Mahayana in the title does not refer to the name of a particular school or tradition, i.e., Mahayana as distinguished from Hinayana, but is used “to reflect the boundless good qualities of the dharma nature,” (Berwyn Watson). Consequently, the word “faith“ in the title “is faith in the true nature of beings and existence – not faith in the teachings of what later came to be seen as the Mahayana school, but faith in what is.” It should not, therefore, be confused with the Judeo-Christian meaning of faith as belief in a sacred text.

Revelation of True Meaning: One Mind and Its Two Aspects

After a rather lengthy introduction, the main text starts in Part Three – Chapter One as follows:

“The revelation of the true meaning [of the principle of the Mahayana can be achieved] by [unfolding the doctrine] that the principle of One Mind has two aspects. One is the aspect of Mind in terms of the absolute (tathata; suchness), and the other is the aspect of Mind in terms of phenomena (samsara; birth and death). Each of these two aspects embraces all states of existence. Why? Because these two aspects are mutually inclusive” (Hakeda translation).

In her book on Original Enlightenment, Jacqueline Stone explains that “many Chinese Buddhists of the Sui (581-617) and Tang (618-907) dynasties were dismayed by so remote a vision of liberation and sought to reimagine it in more accessible ways. In approaching the problem, the Awakening of Faith subsumes the alaya-vijnana concept within that of the tathagata-garbha by redefining the former as none other than the one pure mind as perceived through unenlightened consciousness.” This last statement is key because it amounts to a claim that the alaya-consciousness is not different from the pure mind, and it is only our unenlightened minds that see it as impure, thereby opening up the “ever-present possibility of transforming that mind into the mind of awakening.”

The absolute order and the phenomenal order are “ontologically identical; they are two aspects of one and the same reality.”

Hakeda comments: “Because these two aspects are mutually inclusive”: Reality is conceived as the intersection of the absolute order and the phenomenal order; therefore, it contains in itself both the absolute and the phenomenal order at once. The absolute order is thought to be transcendental and yet is conceived as not being outside of the phenomenal order. Again the phenomenal order is thought to be temporal and yet is conceived as not being outside of the absolute order. In other words, they are ontologically identical; they are two aspects of one and the same reality.” He then presents it as a philosophical reformulation of Nagarjuna’s saying: “Perhaps the most famous and simplest statement of the relationship between the absolute and the phenomenal order can be found in the sayings of Nagarjuna (second century CE), e.g., “There is no difference whatsoever between nirvana (absolute) and samsara (phenomena); there is no difference whatsoever between samsara and nirvana.”

In the very last lines of his introduction, Hakeda also writes that “The approach of the text is dialectical and iconoclastic, yet in the end essentially religious.”Nagarjuna’s statement that “There is no difference whatsoever between nirvana (absolute) and samsara (phenomena); there is no difference whatsoever between samsara and nirvana,” falls in the same category.

The conflation of the absolute and the phenomenal has made possible a revalorisation of the phenomenal that resonated with the Chinese celebration of the “fertility” of the Dao

When Nagarjuna wrote in the Mulamadhyamakakurika“It is dependent origination that we call emptiness. It is a dependent designation and is itself the Middle Path,” he was approaching reality “from the side of emptiness as the absolute truth” in the sense of a subtratum of emptiness, paralleling Brahman as a substratum of being. His language is that of metaphysics, even though he is trying to deconstruct metaphysics. Not only was the self devoid of inherent “being” as the Buddha had taught, but all “things,” arising interdependently, were also devoid of inherent existence, even the “building blocks” of reality, which some scholars at the time still considered to contain svabhava (essence or substance). It is only because what appeared as conventional truth was also empty that it could be described as similar to absolute truth.

Todaiji, Nara

In contrast, in Chinese thought, generally described as “naturalistic,” the emphasis is on the concretely encountered phenomena, the ten thousand things pouring forth from heaven, metaphorically represented by “mountains and waters.” Fazang (643-712), the third Patriarch and systematiser of the Huayan school, wrote a commentary on the Awakening of Faith, and recognised the text as a basic source for his own school, in addition to its central scripture, the Avatamsaka Sutra. The Huayan doctrine can be summarised as an expansion of the concept of co-dependent origination, where all phenomena are described not only as interdependent, but also as including each other. Not only does the whole include all the parts, but every part of the whole reflects the pattern of the whole, much like the DNA in every cell of my body contains the blueprint for all the cells of our body. This led Francis H. Cook, one of the earliest scholars who studied the Huayan school, to assert that its universe is one “in which phenomena have been not only restored to a measure of respectability, but indeed have become important, valuable, and lovely” (quoted by Jin Y. Park). It is not simply a matter of re-evaluating phenomena as “real” because they are empty. This is a true celebration of the “fertility” of the Dao. The teachings of the Huayan school, together with its positive attitude towards phenomena as well as the doctrine of original enlightenment, were adopted by all schools of Buddhism in Japan.

It can be said that the Awakening of Faith indirectly brought to fruition the efforts of Yogacara and Tathagata-garbha to overcome what had led to Indian Mahayana being accused of nihilism. Sunyata was not to be considered a mere “me-ontology” replacing “being” with emptiness in the definition of Brahman as described in the Upanishads. It was the “phenomenal,” which in Buddhism had always been equated with impermanence, and considered the primary cause of suffering. Zhiyi (538-597), founder of the Tiantai school, explicitly presented his central teachings in terms of “entering emptiness from the side of the phenomena.”

Influence of the Awakening of Faith on the Zen school

The terminology used by the author (or is it that used by the translator?) is still uncomfortably “metaphysical” as befits a text authored by an Indian monk. Still it is clear that the Yogacara word “suchness” – things just as they are in our minds – is now used to cover a view of reality as being at once existentially real though illusory, and empty as phenomenal. As such, it heralds the Zen school description of itself as

“A special transmission outside the scriptures

Not founded upon words and letters;

By pointing directly to [one’s] mind

It lets one see into [one’s own true] nature and [thus] attain Buddhahood”

It is also the gist of the teachings of Dongshan (807–869), a prominent teacher in the Caodong/Soto Zen lineage of Dogen, whose teaching on suchness is encapsulated in the short sentence “Just This Is It.” The well-known epigram on “mountains and waters” by the Chinese Zen master Qingyuan Weixin also dates from the 9th century: As a novice monk I saw mountains and waters – A is A. After a short period of training, I saw that mountains and waters were only names pinned on an undifferentiated reality – A is not A. Upon gaining awakening, I fully realised the true nature of the things of the world as perceived: that is, the real is the phenomenal, the real is real in its unreality. A is really A. Now I could see them in their “suchness.” My “no-mindedness” had allowed nature to “nature.” This is referred to as the logic of soku.

In terms of time, the phenomenal is impermanence. Nakamura Hajime stated: “For Dogen, therefore, the fluid aspect of impermanence is in itself the absolute state. The changeable character of the phenomenal world is of absolute significance for Dogen. Impermanence is the Buddhahood … The impermanence of grass, trees, forests is verily the Buddhahood. The impermanence of the person’s body and mind is verily the Buddhahood. The impermanence of the (land) country and scenery is verily the Buddhahood.”Talking about the modern period, Nakamura also says: “What is widely known among post-Meiji philosophers in the last century as the “theory that the phenomenal is actually the real” has a deep root in Japanese tradition,” which was to a large extent shaped by Chinese culture. Kyoto School philosopher Nishitani Keiji (1900-1990) confirms this when he writes: “Precisely because it is appearance, and not something that appears, this appearance is illusory at the elemental level in its very reality, and real in its very illusoriness … After all, we can do no other than to say: it is so.”

The words “relational truth” are often used in modern scholarship to describe a truth that is at once existentially real and objectively illusory.

Sources:

Jacqueline I. Stone – Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism (1999)

Peter Harvey – An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practice (2013)

Francis H. Cook – Hua-yen Buddhism – The Jewel Net of Indra (1977)

Rev Master Berwyn Watson – The Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana: An Appreciation: https://journal.obcon.org/article/the-awakening-of-faith-in-the-mahayana-an-appreciation-part-one/

Taigen Dan Leighton – Just This Is It – Dongshan and the Practice of Suchness (2015)

Nakamura Hajime – Ways of Thinking of Eastern People – India, China, Tibet, Japan (1964)

Nishitani Keiji – Religion and Nothingness (1961)