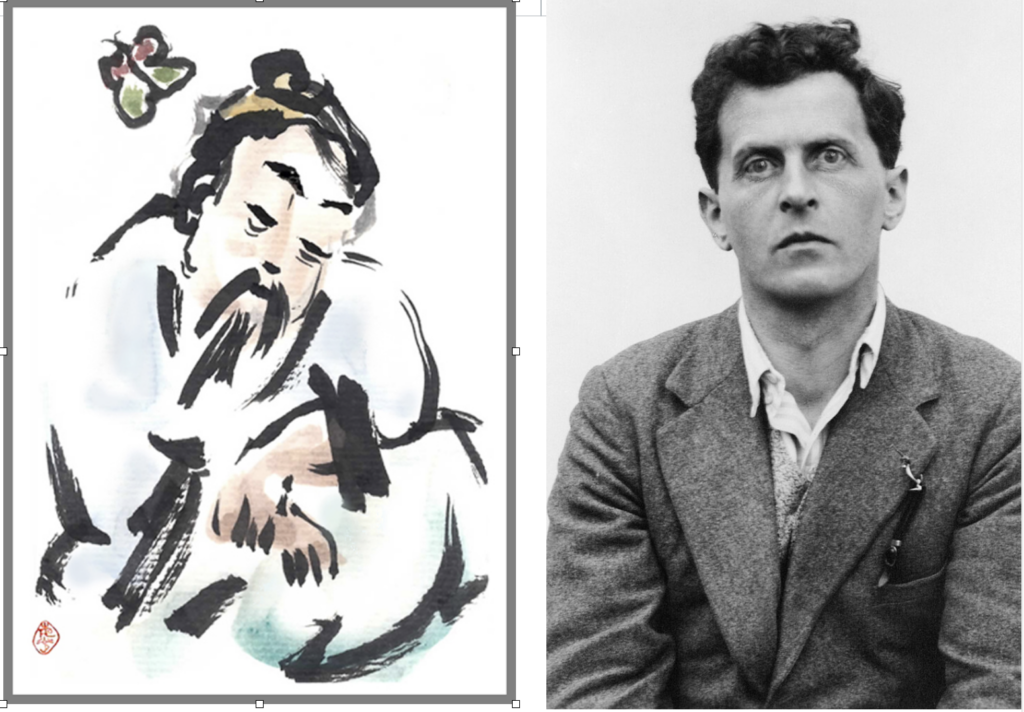

“For Zhuangzi, as for the later Wittgenstein, natural language is groundless. It is a vehicle of communication and intercourse that is a natural to man (and woman) as chirping is to birds and barking is to dogs. How much of it makes sense? How much of it is purposive? How much of it is encoded speaker intentions to be decoded and replied to by a listener per se? Zhuangzi, and Wittgenstein, thus reveal and unleash the functionality and multiplicity of language to press it to – and beyond – its limits, … opening the doors to self-discovery and creativity … And liberating! Zhuangzi’s goblet words thus [lead to] the wisdom of uncertainty.” (Kirill Ole Thompson)

Ludwig Wittgenstein: Against the Correspondence Theory of Language

The correspondence theory of language states that the truth of a statement is determined by how accurately it describes reality. In mainstream Western culture, the assumption is that the words we use to communicate “represent” the things and beings we encounter in the world.

In fact, this claim took shape in the minds of two Greek philosophers, Plato and his disciple Aristotle. Plato defined “what is” as being contained in a transcendental realm of Ideas, pre-existing Forms of which what we see is a copy. Aristotle added that we discover the Ideas by observing the natural world and inferring the transcendental Ideas from their manifestations in reality. This view is the original philosophical definition of the word “metaphysics”—that which is beyond the physical world we experience. It emerged at a specific moment in the cultural history of the West—the fourth century BCE—and marked a turning point in the development of its intellectual and religious life. It is so fundamental to the Western way of thinking that few have ever doubted it. And among those who have come to doubt it, few are able to extricate themselves from it.

Wittgenstein’s career was uniquely divided between the metaphysical views he expounded in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922) and their repudiation in the ground-breaking ideas published posthumously in Philosophical Investigations (1953). In his early period, Wittgenstein believed that a study of the relationships between propositions (i.e., words) and the world would solve all philosophical problems. His view can be summed up as “every word has a meaning. This meaning is correlated with the world. It is the object for which the word stands” and “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

This is the standard correspondence theory of language, based on Aristotle’s assertion that “to “know a thing is to name it.” In Philosophical Investigations, however, the later Wittgenstein no longer believes that language mirrors the structure of reality. Instead he argues that the meaning of words is best understood through their use in what he calls a “language game.” The term “language-game” refers to a context involving interacting actors, where “words” are either “created,” or altered by the “rule” of a particular “game” dictated by what their actions are meant to accomplish. In other words, “words” do not arise from a platonic contemplation on “what is” (“being,” the “on” of “ontology”). They arise from human interaction, in which specific actions require a new level of communication. This is how human language was born in the Paleolithic. This is still how new words are added to dictionaries every year.

Zhuangzi: For a Wisdom of Uncertainty

In his deconstructive analysis of the Zhuangzi, Wang Youru writes: “Zhuangzi refutes the correspondence theory of language. He refuses to surrender himself to the descriptive, cognitive or referential use of language … to overcome the direct mode of linguistic discourse, and best serve the primary purpose of his soteriological or therapeutic practice” (Wang 2003).

Though this theory was argued for in China by the members of the School of Names, these disappeared with the onset of the Qin dynasty (221 B.C.E.), and their ideas never became mainstream in traditional China. As a Daoist, Zhuangzi did not share them. For the followers of the Dao, there is no “ideal” static order embodied in words. The ten thousand things arise for us, as it were, from the Dao, shaped by the interaction of yin and yang, as first described in the Shijing (The Book of Odes), one of the Five Classics, said to have been composed between the eleventh and seventh centuries BCE and compiled by Confucius. Yin and yang act in a way comparable to the polarity of the positive and negative ends of a magnet to guide us on the Path to follow in order to lead lives conducive to the health of the natural world as well as the physical and mental health of the individual. For the individual, however, a practice of self-cultivation is necessary to align oneself with the ever-changing web of interconnected relationships that we call reality. This alignment is not, as in the case of metaphysics, a matter of words and knowledge. It is a matter of behaviour and actions. Knowledge can only follow the actual change in one’s behaviour in accordance with the “intimations” of the Dao. The role of the sage, according to Zhuangzi, is to guide students of the Way in the practice of self-cultivation to enable them to align with the Dao, and for this he has to use words “creatively.”

Crisis of Meaning in the West

It took Western philosophy two thousand years to move away from the correspondence theory of language. Wittgenstein’s contemporary philosopher Martin Heidegger also came to conclusions that, from another angle, undermine the metaphysical foundations of Western culture. The postmodern movement that followed went even further when it asserted that there is no “truth,” adding that what is presented as “knowledge” is merely a “narrative,” a “story.” So far, however, this has done little more than trigger a “crisis of meaning” among intellectuals, while apparently enabling some to feel free to use blatant “lies” to bolster their quest for power. What the postmodern thinkers have forgotten to mention is that a self-cultivation practice is required to allow us to align experientially with reality “before naming.” Without such a lived realisation, few people in the West can even comprehend what it means to abandon the quest for certainty. And after centuries of scientific and technological research seeking certainty, who will dare to suggest that we should now seek a wisdom of uncertainty?

Sources:

Kirill Ole Thompson – Zhuangzi and the Quest for Certainty in China-West Interculture: Toward the Philosophy of World Integration – Essays on Wu Kuang-ming’s Thinking, Edited by Jay Goulding (2008)

Wang Youru – Linguistic Strategies in Daoist Zhuangzi and Chan Buddhism: The Other Way of Speaking (2003)