“To know a thing is to name it, and to name it is to attach one or usually more universal predicates to it. Not only is the fixed within the flow alone knowable, but the universal in the individual as well. There is no place for the flow to be known as flow, nor the individual as individual. These defects Nishida set about to repair.” (Robert E Carter, The Nothingness Beyond God – An Introduction to the Philosophy of Nishida Kitaro, 25-26)

Moving on after the Inquiry

In “My Philosophical Path,” Nishida tells us how his thought advanced from the idea of “pure experience” to the “logic of basho,” via a focus on intellectual intuition and a study of the workings of self-consciousness, from 1924 onwards, to finally find its apex a decade later with another great Nishidan idea – the logic of self-contradictory identity. Michiko Yusa notes that Nishida first used the word “contradictory” in 1934 (Yusa, Zen & Philosophy – An Intellectual Biography of Nishida Kitaro, 259).

“People say I am always discussing the same problem. That may be true. Since my first book, An Inquiry into the Good [1911], my aim has been to approach things from the most immediate and most fundamental standpoint, and my goal has been to capture this standpoint, from which everything emerges and to which everything returns.

Granted, the expression ‘pure experience’, which I adopted in my first book, had a psychological overtone. But at least in my mind, it was a standpoint that transcended the dichotomy of subject and object, and I tried to investigate the objective world also from that standpoint … In my mind, ‘intuition’ was not something that transcended the operation of consciousness; rather, it was that which establishes the operation of consciousness itself” (Nishida, “My Philosophical Path,” quoted by Yusa, Ibid, 301).

Though Nishida continued to use the words “pure experience” for some time, he eventually came to feel that both William James and Henri Bergson, who had guided the first steps of his inquiry, were still under the spell of Western philosophy’s emphasis on concepts, though aware of how problematic they were, and unable to break free from the objectifying stance. He instead chose to focus on the continuity between the “ideal elements” created and the experiential flow of raw reality, to assert the presence of a unity behind the apparent rupture. What Nishida had called “intellectual intuition” was “pure experience” broadened to include “ideal elements.” It was “a grasping of “ideal” objects, such as the “unity” that underlies all awareness. Nishida tells us that it is an enlargement or deepening of pure experience.” (Carter, The Kyoto School, 28) “A true intellectual intuition is the unifying activity in pure experience” (Nishida, Inquiry, 32).

It must be kept in mind that this integrated apprehension of concrete reality beyond the dichotomy of subject and object is a direct apprehension of the workings of consciousness in the present moment, this is how a world is created in the here and now of our everyday lives. Such is not the usual stance of the student of Western philosophy, who seeks to understand “how the world works” not just now, but in general – in theory – as world, without concern for how it is actually working right now. For Nishida, reality as experienced is reality as unfolding in the present moment. Anything else is memory, planning, representation of some sort.

In the years following the publication of the Inquiry (1911), Nishida wrote a number of essays in which he tried to clarify the workings of self-consciousness. These were published in 1917 under the title Intuition and reflection in self-consciousness. Nishida, however, was so dissatisfied with the results of his investigation that he at first opposed their publication!

Nishida’s perspectival turn: self as topos (basho)

A breakthrough came between 1924 and 1926, when, according to Michiko Yusa, traces of the perspectival turn which led to the concept of basho are discernible (Yusa, Zen & Philosophy, 202). It all started with a criticism of the phenomenological method which had, in his view, failed “to totally eradicate the objectifying stance.” It had bracketed the contents of consciousness, but it had retained the “inner perception”, that is a standpoint based on the subject. Consciousness was assumed to be an activity carried out by the self as conscious subject, what Aristotle called the grammatical subject. What has been called Nishida’s Copernican Revolution is that he came to see the self “topologically,” as the self-determination of the field of consciousness.

This is how Nishida explains the evolution of his thought in “My Philosophical Path”:

“For a philosophical system to stand on its own, a logical system is necessary. I grappled with this problem until I found a clue in my essay, “Topos” [Basho, 1926]. I was guided by Aristotle’s definition of hypokeimenon in arriving at this idea. But Aristotle’s logic, in which the grammatical subject holds the central place, cannot deal with the reality of the self-conscious self. The self is not something objectifiable, and yet it is something we can think about. This indicated to me that there is another mode of thinking. In contrast to Aristotelian logic, which focuses on the grammatical subject, I called the other mode of thinking the “logic of the grammatical predicate” or “predicate logic.” The self, as the unifier of consciousness, is not something that can be conceived as a grammatical subject. Rather, it is thinkable “topologically” as the self-determination of the field of consciousness” (Nishida, “My Philosophical Path,” quoted by Yusa, Ibid, 301).

“Basho” is the Japanese word for the Greek “topos,” i.e., place or field. Nishida says that he was “guided” to it by Aristotle’s hypokeimenon. Hypokeimenon, in fact, means “material substratum”, a concept radically alien to Nishida’s thought! The material substratum is, in Greek metaphysics, the substance which persists through change. Nishida, however, was really inspired by the image of the place, or field. His basho is a field of nothingness, not a field of substance! Had he looked at Chinese thought instead, he would have found in the Dao, which has both a spatial and a dynamic dimension – as a womb-like source and a way – a similarly inspiring metaphor. In fact, Nishida also traced basho to Plato’s khôra (or chora”) in the Timaeus, which also has a womb-like function (Yusa – Zen and Philosophy, 203-204). Basho will be defined as that out of which phenomena arise through the self-negation of nothingness, i.e., a source of life. As the self is normally assumed to be a point, like an agent within – the little man imagined to reside on one’s forehead! the metaphor of a field suggested by hypokeimenon was particularly effective at inverting the view. The self was not a point inside my brain, it was the whole field of my consciousness, in other words, the world itself not as reflected in my consciousness, but as expressed and shaped by my consciousness, and that of all the other conscious people around me.

Aristotle as the father of Western substantive thinking

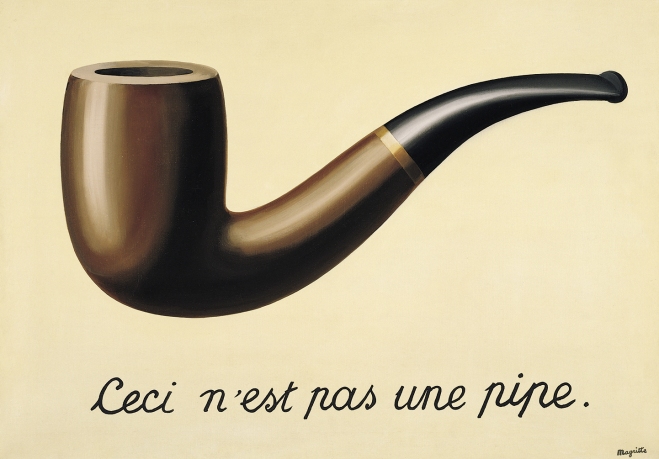

“It is Aristotle whom Nishida takes as the substantive beginning of the Western approach to knowledge” (Robert E Carter, The Nothingness Beyond God, 21). For Aristotle, “to know a thing is to name it.” (Carter, Ibid, 25). In fact, the notion that “thought and being are the same thing,” (to gar auto noein estin te kai enai) goes back to Parmenides, or at least to Plato’s interpretation of Parmenides. But it is in Aristotle’s writings that what Nishida calls “object logic” reaches its highest level of sophistication. Nishida uses the word “logic” in a wider sense than we are used to. For him, “Logic is the form of our thinking” (Carter, The Nothingness Beyond God, 17). “Object logic,” therefore, is what we would call “objective thinking.”

“That it is” and “what it is,” – how Aristotle failed to reach a knowledge of the particular

For Aristotle, “the world lends itself to the grasp of language, it has a ‘logical’ or ‘discursive’ character, a systematic structure” (John Herman Randall, Jr., Aristotle quoted by Carter, Ibid, 21). As Carter explains, “knowledge becomes, on this view, a linguistic matter, and not a matter of sensation. To know is to define … To define, i.e., to know, a thing is to say what kind of a thing it is” (Ibid, 21). Nishida’s early foreys in his inquiry into true reality had led him to follow James’s pure experience to apprehend reality as a great “that,” “plain, unqualified actuality, or existence, a simple that” (William James, Essays in Radical Empirism quoted by Carter, Ibid, 4). For Aristotle, the real is not the actual, “that-it-is,” it is the conceptual, the “what-it-is.” Because of this, “that which is knowable in Aristotle’s logic is the general or universal, but never the particular” (Carter, Ibid, 21-22).

But, aren’t our lives, always, and necessarily, lived in the particular? What I see in my garden is a particular flower, or a particular bird, not flower as such, or bird as such. The East has always been intent on knowing the particular. The Chinese Book of Changes – Yijing (or I Ching) – was a formidable effort to grasp the elusive processes behind the changes observed in the phenomenal world. Of course, the Yijing was a work of divination, using images to prod the imagination as it tries to predict the unfolding of a particular situation. Nishida is not suggesting a return to divination, but he shares the East’s deep conviction that true knowledge is knowledge of the particular. In fact, as Nishida points out, Aristotle held a similar stance when he criticized Plato’s understanding of “Ideas” (the eidetic Forms which are true being) as being seemingly given from above: for Aristotle, the Ideas, that is, the universals, could only be abstracted from the particular things in which they were embodied. Aristotle’s focus on the particular was, however, derailed by the fact that, in order to know what a particular thing is, one needs to use universals. For instance, as I look at the particular flower in my garden, I know what kind of thing this flower is by applying to it the universal called “flower”. The act whereby the particular is known through the superimposition of a universal is called predication. Plato and Aristotle are said to “systematically subordinate the notion of existence to predication; and both tend to express the former by means of the latter. In their view to be is always to be a definite kind of thing: for a man to exist is to be human and alive, for a dog to exist is to be enjoying a canine life (Charles H Kahn, “Retrospect on the Verb ‘To Be’ and the Concept of Being” in Knuutilla and Hintikka eds, Logic of Being quoted by Carter, Ibid, 22). In other words, the “that it is” of a thing is expressed as – and at the same time concealed as concrete existence by – “what it is.” Nishida’s main disciple, Nishitani, writes: “In order to approach the fact that fire is, reason invariably goes the route of asking what fire is. It approaches actual being by way of essential being” (italics added). And he adds: “This standpoint does not enter directly and immediately to the point at which something is. It does not put one directly in touch with the home-ground of a thing, with the thing itself” (Nishitani Keiji, Religion and Nothingness, 114-115). What a thing is does not allow you to grasp existentially that it is, its actuality, or existence, or presence.

Nishida, who had himself asserted that “Aristotle, in opposition to Plato, sought the ground of truth in individual things” (Nishida, Fundamental Problems of Philosophy translated by David A Dilworth, 4), was quick to see a contradiction between Aristotle’s focus on the individual as the ground of truth, and an approach to knowledge which required the predication of universals, with the result that, in the end, the individual as a unique existence arising in the present moment was, as it were, hidden by the universal, and therefore, unknowable. This had happened because Aristotle’s thought had been shaped by a philosophical tradition which valued the static over the changing. “Greek philosophy considered that which transcends time, the eternal, to be true reality, and, on the contrary, that which moves in time to be imperfect” (Nishida, Ibid, 39). The same distrust of change, and emphasis on the unmoving is found in Indian philosophy which has agonized for centuries over a clarification of the apparent contradiction between an Absolute Being – Brahman, which, by definition, is unchanging, and the fact that all phenomena arise from it, which cannot happen without Brahman’s ability to produce change. Only in the Far-East, where change is the core tenet of Daoism, has a dynamic understanding of reality endured.

West: true reality is unmoving, it is what transcends change – East: true reality is dynamic, it is change itself

For Aristotle, then, true reality is unmoving, and that which moves is not really real, so to know that which moves, we must predicate on each moving thing a universal which will reduce it to a fixed entity. The multifarious exhuberance of the aboriginal flow described by James is stripped down to a set of “facts”and events unfolding along fixed lines, as laid out by the universal concepts superimposed on concrete reality. Compare how a Western scientist and a Daoist master would describe how an acorn becomes an oak tree. The Western scientist would explain that the oak tree produces acorns which fall to the ground, germinate, and in time grow into new oak trees. The Daoist master would point out that, out of the many acorns produced by the oak tree, quite a few would be eaten by squirrels (or woodpeckers), most would fall in wet patches where they would rot, so only a few would germinate, and most young oak trees would be cut down by farmers. On one hand, the abstract theory, on the other, actual concrete reality as it is experienced. On one hand, the appearance of a fixed reality, on the other, the focus on the contingent particular of real everyday life.

Carter sums up: “To know a thing is to name it, and to name it is to attach one or usually more universal predicates to it. Not only is the fixed within the flow alone knowable, but the universal in the individual as well. There is no place for the flow to be known as flow, nor the individual as individual. These defects Nishida set about to repair” (Carter, Ibid, 25-26).