For people who are new to the study of Daoism, the word yinyang is associated with the School of Yinyang (yinyangjia) which emerged into history as one of the Chinese schools of thought that took part in the Jixia Academy during the Warring States period.

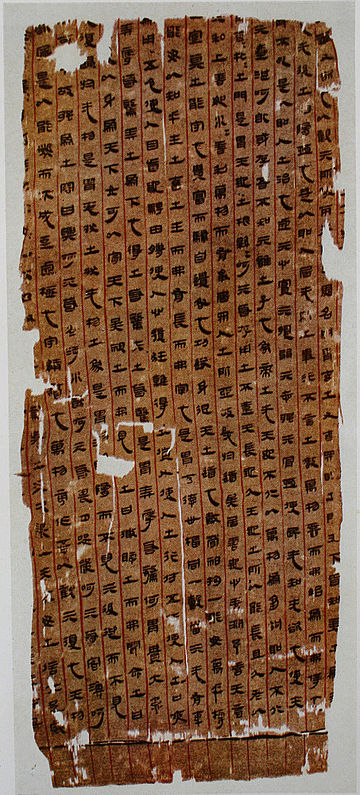

In fact, by the time of Zou Yan (305 BC – 240 BC), who is regarded as the founder of this school, the words yin and yang had been used by ordinary Chinese as well as scholars for many centuries. They do not, as such, go back to the oracle bones of the Shang Dynasty or the bronze inscriptions of the Western Zhou Dynasty, which are the oldest written sources available on China’s early history. But, Robin Wang notes, “there are a few words that might be related to the creation of the characters for yin and yang, particularly the character for yang, given its close connection to the sun. Three of the earliest six Chinese characters that have been found in Dawenkou culture (4300-2500 BCE) are related to the sun. Given the fundamental importance of the sun and its connection to yang, the character for yang might have appeared earlier than did the character yin.”

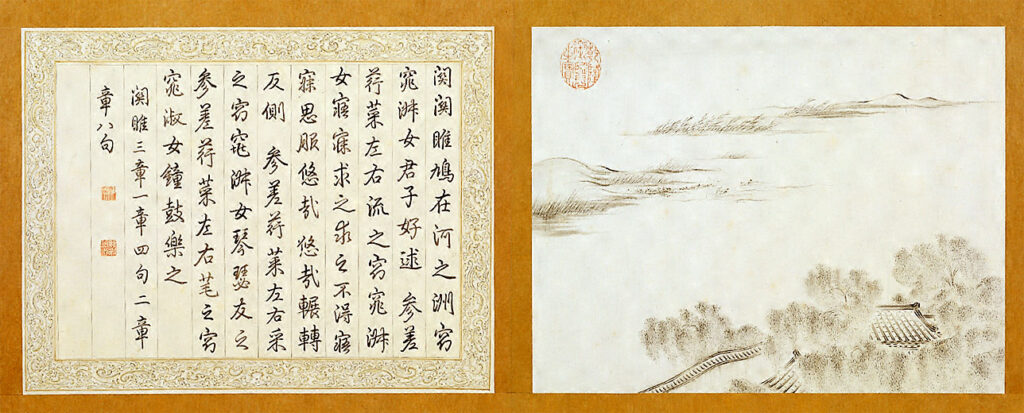

This may come as a surprise to some, given the emphasis placed on the interdependence of yin and yang by the yinyang scholars. In the Shangshu (The Book of History), one of the Five Classics said to have been compiled by Confucius, both terms appear but not together. Wang writes: “The term yang appears six times in the “Yugong” chapter. Five out of the six characters refer to mountains or the south side of a mountain. The term yin appears three times in the book, referring to the north side of a mountain. From this, we can see that in the Shangshu, the terms yang and yin are geographical terms used for specifying a location.”

Only in the Shijing (The Book of Odes), also one of the Five Classics, do the words appear together in the following sentence: “Viewing the scenery at hill, looking for yinyang.”Wang comments that this “indicates that yin and yang in their earliest usage were separate terms that were connected to label the result of the sun reflecting on the hill. The sunny side of the hill is yang, and the shady side is yin.” In other words, “yinyang depicts the interplay between the sun, a hill, and the light.” So, “yinyang is not a particular object but rather a phenomenon: the features of the sun as they relate to other things. In this sense, yang is quite different from the sun itself, ri. The sun is an entity, a being, a particular object, however, yang is the effect of this entity and not the entity itself. In their earliest uses yin and yang are not substances but functions of something, and they are inevitably attached to relationships or contexts. Any fixed definitions of yinyang will, thus, lead to a problematic understanding of the terms. As we already see, yinyang thought was inspired by human experience of the sun.”

What turned out to be one of the core insights of the Chinese worldview was indeed very different from what took place in the West where, in Heidegger’s words, “thought and being are the same thing,” (to gar auto noein estin te kai enai), and being as synonymous with “substance,” the static within the dynamism of life. China is not, of course, the only land where the world was originally approached as the dynamism of “life.” Most indigenous cultures still living according to their traditions also do. But what is fascinating with China is that we can go back to its founding texts and see how this insight arose and was able to survive against all authoritarian assaults, including that of our own western mode of thinking.

Originally, Wang notes, it provided “a clock for daily routines. Farmers depend on it for light, which in turn dictates the daily rhythm of human life. As the Shijing says ‘when the sun is coming out, one goes to the fields, and when sun is going down, one goes to rest’. The steady rhythmic alternation of yin and yang can be seen as expanding from this basic human experience.” This is why the French sinologist Marcel Granet “takes the fundamental dimension of yinyang thinking as being ‘the idea of rhythm’. In keeping with the effects of the alternation of day and night on human beings, yang is associated with movement and action, whereas yin is associated with rest and stillness.” From the Chinese example as well as those found in today’s indigenous cultures, one could suggest that a strong link exists between societies engaged in farming and a view of reality as a dynamism, since farming could be defined as the art of “cultivating life.” In the West, waves of invasion by traders and warriors, were cut off from the peaceful art of “cultivating life.” No wonder then that what is simply referred to as “practice” in Indian spiritualities, is called “self-cultivation” in East Asia.

Wang also draws our attention to the connection between yinyang and the sun. Of course, the sun provides both light and warmth, which are beneficial to farming, but beyond this it is a huge presence in the sky that has fascinated humans in China and in most parts of the world. Wang notes that

“In the Zhou Dynasty, the highest divine force was tian, conventionally translated as “heaven,” however, a term which could also mean the sky. The Zuozhuan (Chronicle of Zuo or Commentaries of Zuo), an early history text covering the period from 722-468 BCE, and one of the important sources for understanding the history of the Spring and Autumn Period, claims that ‘from the sun one will know there is the way of heaven’.” And from there to the constellations of stars that kept Chinese astrologers observing the night sky, there was but one step. “In early times, the commands or mandate of heaven (tianming), were revealed in the movements of the constellations. The movement of the sun, moon, and stars were all expressions of heavenly will. Because the will of heaven is apparent through events in the sky, one can look to the sky to know the will of heaven … Heaven also expresses its will through the different seasons, which are produced by the sun.”

This last sentence could be interpreted as meaning that humans naively believe that they must “obey” the commands of the sun – and the moon and stars – to avoid their displeasure and incur their wrath. What it really means is that “human action must be synchronized with the movement of the sun,” in other words, reality as a whole, i.e., what we would now call the requirements of our biosphere. Wang notes that the Chinese word for “seasons,” shi, is “the word for acting in a timely way. The character itself includes an image of the sun.” The English “season” has a similar origin: sowing.

No wonder then that, “the development of yinyang thought was largely concomitant with the theorization of Chinese astrology. The sky concerns both the calendar and the seasons as they relate to farming and ritual …. Here we see the interconnection of different levels of phenomena, something typical of yinyang thought …. [The] whole structure of time was conceived through the flowing of yinyang, thus making yinyang the basis for human activities …. One needs to follow the decline and growth of yinyang …. The sun and moon, joined together, provide a guide for farming. The classical Chinese ‘day’ (ri) is the same word as ‘sun’, just as “month” (yue) is the same word as ‘moon’.” The moon has an indispensable role to play, because individual days (ri, representing the sun) are situated within months (yue, representing the moon).” In fact, moon is also the origin of the English word “month. It represents the time it take for the moon to complete a cycle around the earth. And in Old English a “day” (dg) is a period during which the sun is above the horizon. The attempt to “reconcile human life with the sun” is made explicit in the characters for yin and yang. “The character yin shows a mound on the left side, with a cloud on the bottom left, below the symbol for today. The traditional character for yang shows a mound on the left side, with a sun on the top right. Part of yang in Chinese is ri (sun). The right side of the yang character can further be grouped as dan (daybreak, i.e., the sun coming over the horizon) and yang (bright, i.e., light streaming of the sun), which both directly relate to the interpretation of yang as “sunny.”

From the Terms Yin and Yang to Yinyang Thinking as a Paradigm

As noted China is not the only land where the sun, along with the moon and stars, were worshipped in connection with their roles in the lives of early farmers, as guides in sowing, and other phases of plant growth, but it is the only part of the world where this role gave rise to a binary mode of thinking, that allowed ordinary people to make decisions moment to moment, as their lives unfolded, to remain “aligned” or “attuned” with the world at large.

Wang explains that “historically, although the term yinyang was not a dominant concept before the Han Dynasty, proto-yinyang thought already existed and had given rise to a particular thinking model.” Three main constituents contributed to the formation of yinyang thought: the practice of divination based on the Yijing, a rationalizing tendency in relation to natural processes, and yinyang’s link with qi.

The practice of divination

In the Shijing (The Book of Odes), where, as we saw, the two words were linked for the first time, “sun and moon divination is used to predict good or ill fortune …. In the Shang Dynasty, divination was consulted widely for a broad range of activities … hunting, getting married, going to war … All of these questions were divided into “yes” or “no” – two aspects.”

But, of course, Wang writes, “This kind of binary structure appears most clearly in the Yijing (The Book of Changes) …. The diviner would make marks on the tortoise shell, then burn it and read the cracks. Another method is wu which uses stalks or other sticks that are divided and shuffled according to a certain procedure. The cracked lines or the arrangement of the sticks all point toward of one or two possible results: well-fortuned or ill-fortuned, yes or no .… The binary structure of these divination methods reveals a value and belief system that became deeply integrated with yinyang thinking ….Such a binary system underlies the structure of the Yijing; this system was explicitly connected to yinyang through the Yizhuan (Yi Commentaries), which were probably written in the late Warring States Period.”

Rationalizing tendency in relation to natural processes

“According to contemporary Chinese scholar Chen Lai, in the Spring and Autumn Period (770 to 481 BCE), there was a growing tension between worldly political and moral consciousness and the tradition of spirit worship.” Divination was criticised, and yinyang was used to explicate natural events, so that human knowledge does not depend on divination or spirits. Wang tells us that, asked about two exceptional events recorded in the Zuozhuan – a shooting star and six birds flying backwards, “Shi Shuxing responded that these are ‘the events of yinyang, not issues of being well or ill fortuned’. This is a bold claim, because it marks a transitional time when yinyang was used as a conceptual tool to clarify natural phenomena and when it provided a break from treating those events as auspicious signs determining human events …

In the West, too, starting in the 6th century BCE, the Presocratics carried out a rationalising process in the way they described natural phenomena (physis) and this led, in time, to Aristotle’s elucidation of the “principles of reason,” in particular the principle of non-contradiction, stating that contradictory propositions cannot both be true at the same time. In China, however, what is described as a “rationalisation” led to the exact opposite of the paradoxical interdependence of opposites. Wang tells us that “the earliest detailed view of this way of thinking appears in the Daodejing, a text expressing thought that probably developed in the 5th century BCE … According to Liang Quichao (1873-1929) … although there is only one use of the term yinyang in the Daodejing, the text has a persistent orientation the paradoxical interdependence of opposites in the world. ”See, for instance, chapter 2:

“Everybody in the world knows the beautiful as beautiful. Thus, there is already ugliness. Everybody knows what is good. Thus, there is that which is not good. That presence and non-presence generate each other, difficult and easy complement each other, long and short give each other shape, above and below fill each other, tones and voices harmonize with each other, before and after follow each other is permanent.”

“Overall,” Wang notes, “the DDJ presents at least thirty five such pairs of opposites, and they exhibit many of the same characteristics later taken up by yinyang theory. For ex., these forces engage in constant transformation and generation.”

Link between qi and yinyang

As a word, “qi” goes further back than yinyang, as it has been identified in both the oracle bones of the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE) and the bronze inscriptions from the Western Zhou Dynasty (12th century-770 BCE). From its original meaning of “vapour,” it had come to take the meaning of life force and become “one of the most basic concepts for explaining change in the natural world.” In the words of the contemporary Hungarian sinologist Sandor P Szabo, “Numerous thinkers believed that there is a material substance, a ‘basic stuff’ in the universe, the primary material of universe … the coming into being of all the existing things is the result of the concentration of qi and their decay is the result of the dispersal of qi.”

In the Zuozhuan (Chronicle of Zuo or Commentaries of Zuo), which covers the period from 722 to 468 BCE, yin and yang are listed as two of six heavenly qi: “Those six qi are denominated the yin, the yang, wind, rain, obscurity, and brightness. In their separation, they form the four seasons; in their order, they form the five (elementary) terms. When any of them is in excess, there ensure calamity. An excess of yin leads to diseases of cold; of the yang, to diseases of heat.”

Wang says that “The development of qi theory elevated the role of yinyang as the dominant modes of qi, thus as explaining all kinds of natural phenomena. Building on these proto-yinyang sources, an explicit yinyang thought paradigm emerged throughout many texts in the late Warring States Period (475–221 BCE) and early Han Dynasty.” This includes a major turn with the Jixia Academy in 318 BCE and the foundation of the Yinyang School (or School of Naturalists) by Zou Yan (305-240 BCE).

Source:

Robin R. Wang – Yinyang: The Way of Heaven and Earth in Chinese Thought and Culture (2012)