“As a lamp, a cataract, a star in space, an illusion, a dewdrop, a bubble, a dream, a cloud, a flash of lightning, view all created things like this”

A key Mahayana text with controversial origins

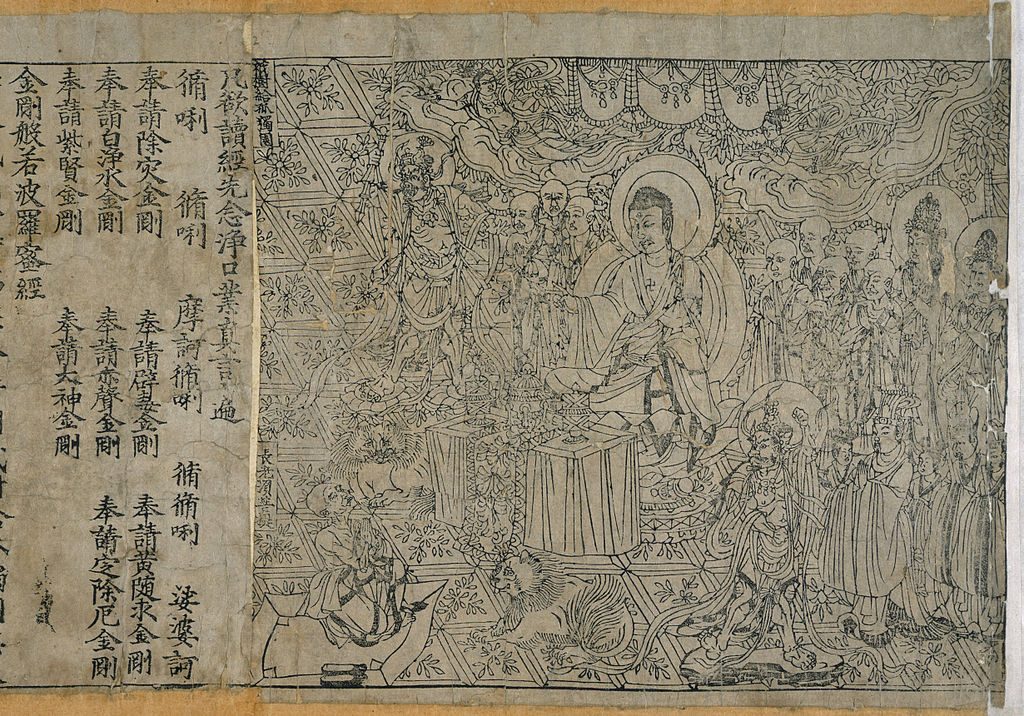

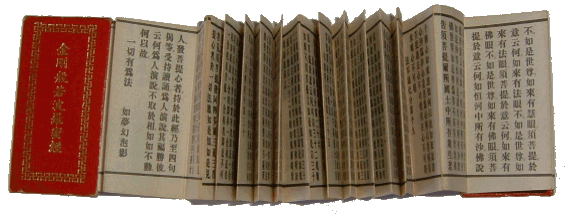

The Diamond Sutra and the Heart Sutra are the two best-known and best-loved sutras of the series of texts known as the Prajnaparamita sutras. A printed copy of the Diamond Sutra dating from 868 was retrieved from the Dunhuang Cave, and is currently regarded as the earliest complete dated printed book ever found.

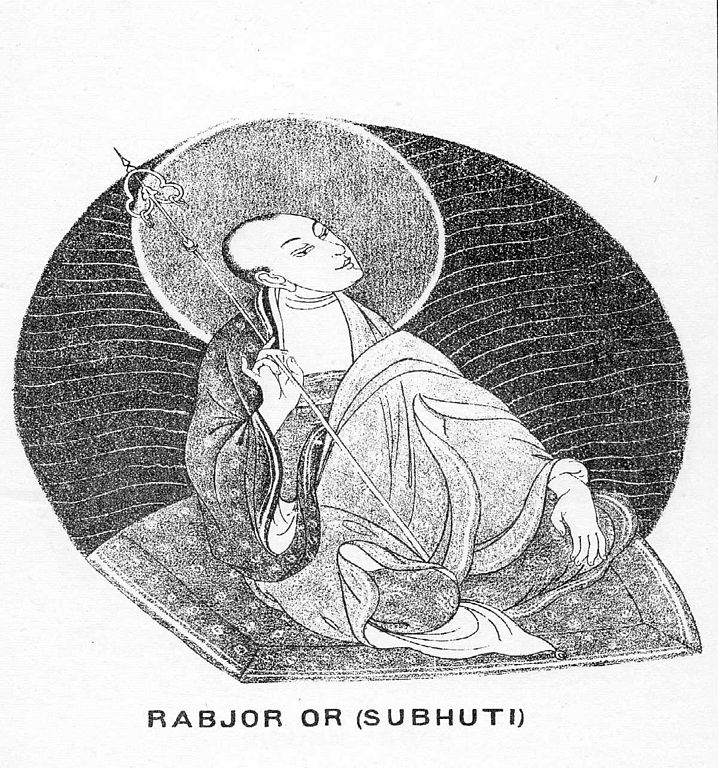

Paul Williams writes that the date of composition of the Diamond Sutra is still being debated between the scholars who argue for a late composition (2nd to 5th century CE), and those, among whom some Japanese scholars and Gregory Schopen, who believe that the text in its oral form pre-dated the Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita Sutra, traditionally regarded as the first Prajnaparamita text dated 100 BCE. If that view is correct, the Astasahasrika Sutra could be an expanded reworking of the Diamond Sutra. Red Pine (Bill Porter) would support this early date, as the Diamond Sutra presents the Buddha teaching the various stages leading to Buddhahood in the Bodhisattva path to Venerable Subhuti, then an Arhat in the Sravaka tradition. In the Astasahasrika Sutra, though the Buddha is still present, Subhuti, having reached Buddhahood, often assumes the teaching role.

Though the better known Chinese translations are in prose, the original Sanskrit text was in verse, with a distinct poetical rhythm, and a strong reliance on repetition. This was a text designed to be learned by heart and recited during practice. As indicated in the text on the Prajnaparamita sutras, such texts were “embedded in religious practice.” Hence their repetitive style, reiterating after each assertion about a “thing” a “being” or an “action” that it is not, as, for instance, “though I thus liberate countless beings, not a single being is liberated” or ““while practicing the six paramitas … we practice nothing at all” (Williams). Just as in the case of the Heart Sutra, there is a cumulative effect produced by such repetitions, what we could call a “deconstruction,” immediately undermining “svabhava,” the apparent solid substantiality of every thing we may have appeared to posit. This “undermining” is the activity of Perfect Wisdom.

Perfect Wisdom, as compassionate understanding, is what makes a Bodhisattva

As Red Pine, the author of the translation used here, explains, the full Sanskrit name of the sutra is Vajracchedika Prajnaramita – the diamond-cutting Perfection of Wisdom, in a sensemade clear in the Nirvana Sutra, where the Buddha says: “Prajna is like a diamond. While nothing is able to harm it, it can cut through all things.” As he takes Subhuti through the various stages of the Bodhisattva path, the Buddha shows how the way Perfection of Wisdom cuts through all things, including the practice itself, exposing their lack of “intrinsic nature,” thereby “emptying” them, and allowing the future Bodhisattva to develop both boundless compassion and a deeper understanding of all things and beings. Thich Nhat Hanh feels uncomfortable with translating prajna as “wisdom,” arguing that wisdom is “solid” and prefers to translate it as “understanding.” He writes: “Understanding like water, can flow, can penetrate. Views, knowledge, and even wisdom are solid, and can block the way of understanding.” Given the impoverished meaning the word “wisdom” has been reduced to in the modern period, “understanding” may be a more suitable term to refer to prajna’s intuitive knowledge of reality as if from within, an empathetic embrace. The French “com-prendre,” to which Thich Nhat Hanh may feel closer, describes prajna even better. “Under-standing” denotes a knowledge gained through finding out what stands under a thing, its cause, while “com-prendre,” like “comprehend” grasps the whole in one enveloping insight.

From the Sravaka path to the Bodhisattva path

Red Pine explains that Subhuti was “foremost in his freedom from passions” that is, he was an Arhat (Red Pine says Ahran) who had successfully followed the Sravaka path (the Path of the Disciple) taught in the mainstream Theravada school to attain Arhatship – basically, release from the round of rebirths – along the lines of what that school regarded as the original teachings of the Buddha. Subhuti was regarded as having arrived at his last incarnation. He was the one among the Buddha’s disciples who had best “understood the doctrine of emptiness”: his very name, Subhuti, meant “born of emptiness.”

The Buddha addressing Subhuti will therefore tease out what he sees as the shortcomings of the Sravaka path when compared to the Bodhisattva path, which brings him to focus on compassion and the correct understanding of emptiness.

The teaching is set as one given by the historical Buddha, thereby claiming a direct transmission from the same historical Buddha as that claimed in the texts held by the Theravadins as the true teachings of the Buddha. According to Red Pine, the Theravada sutras reflected the early teachings of the Buddha, which were collected and read at the First Buddhist Council, shortly after the Buddha’s paranirvana. The Mahayana sutras were based on later, more advanced teachings, inspired from the very career of the Buddha, the way he himself had vowed to liberate others out of compassion. These are said to have been transmitted esoterically until a larger number of followers were able to understand them.

Bodhi-citta and Bodhisattva Vow

The Diamond Sutra stages the new teaching as an actual event which took place at one of the assemblies where disciples gathered around the Buddha to listen to his sermons. It starts with the Buddha sitting down “on the appointed seat. After crossing his legs and adjusting his body, he turned his awareness to what was before him.” Subhuti then rose from his seat, and asked: “Bhagavan, if a noble son or daughter should set forth on the bodhisattva path, how should they stand, how should they walk, and how should they control their thoughts?

The Buddha’s reply is as follows:

“Subhuti, those who would now set forth on the bodhisattva path should thus give birth to this thought: ‘However many beings there are in whatever realms of being might exist, whether they are born from an egg or born from a womb, born from the water or born from the air, whether they have form or no form, whether they have perception or no perception or neither perception nor or no perception, in whatever conceivable realm of being one might conceive of beings, in the realm of complete nirvana I shall liberate them all. And though I thus liberate countless beings, not a single being is liberated.”

So, here we have, at the starting point of the Bodhisattva path, the thought known as the bodhi-citta, the thought of “awakening.” This is not what Subhuti expected. The Sravaka path he had followed relied on moral discipline and meditation to achieve the non-attachment required to realise no-self. In the Bodhisattva path, the arising of compassion for others, and the aspiration to help them achieve liberation, is said to mark the entry into the path, formally confirmed by the Bodhisattva Vow. In addition to that vow, however, is the following unexpected qualification: “And though I thus liberate countless beings, not a single being is liberated.”

Red Pine comments: “Instead of telling us how to conduct our lives and our practice or how to control our thoughts, the Buddha tells us to give birth to a thought. The Buddha’s approach is homeopathic. He uses a thought to put an end to all thoughts. But … only a thought directed towards the liberation of all beings will work. Thus, bodhisattvas turn their thoughts into offerings.”

Giving as the most important paramita

The Buddha goes on to tell Subhuti “that the bodhisattva’s practice only succeeds if it is devoted to the liberation of all beings and at the same time detached from the perception of being.” The formula used in the sutra is that “No one can be called a bodhisattva who creates the perception of a self or who creates the perception of a being, a life, or a soul.” Repeated a number of times throughout the text, this sentence is said to be the “gatha” which the Buddha himself hints at, without naming it, encapsulating the core teaching of the sutra. In concrete terms, this no creating of a perception of being will be embodied by non-attachment to the act of giving (liberation to others) as well as non-attachment to the actual gift of liberation. Red Pine quotes Lin-chi, founder of the Rinzai school, saying: “By not dwelling on anything, bodhisattvas do not see the self that gives, nor do they see the other that receives, nor do they see anything given. For all three are essentially empty. By concentrating without concentrating on anything, their practice of charity remains pure.” They are like the sun and the rain nurturing all life-forms on earth, without the least awareness of it, as they are just expressing what they are.

Of all the paramitas (perfections) listed in the Bodhisattva path, most of which were also practiced by the Sravakas, giving (dana) is the most important one: it is literally the one that launches the aspiring Bodhisattva on the path. Once on the path, one should walk it with the additional practice of the other five paramitas – morality (or precepts, sila), endurance (ksanti), exertion (virya), meditative concentration (dhyana), and of course wisdom/understanding (prajna). Giving, however, is said to be the most important, as it is the only paramita “directed exclusively at liberating others.”

This being said, Red Pine, emulating the Buddha reminds us “while practicing the six paramitas … we practice nothing at all.”

The main teaching of the Diamond Sutra is in its first five chapters.

We have now reached Chapter 5. The elements of the teachings listed so far are the bodhi-citta or thought of awakening – an arising of compassion and the wish, confirmed by a vow to liberate all beings whereby the path is entered; a practice of non-attachment to the act of giving, and what is given (liberation); a practice of charity and other paramitas to walk the path. At the same time an awareness that there are no beings to liberate, no perception of a self, a life or a soul, no paramita to practice … The last teaching at the beginning of Chapter 5 concerns the possession of attributes.

The Buddha asks: “Can the Tathagata [the Buddha] be seen by means of the possession of attributes?” Answering his own question, he says: “Since the possession of attributes is an illusion, Subhuti, and no possession of attributes is no illusion, by means of attributes that are no attributes the Tathagata can, indeed, be seen.”

Red Pine explains: “Every object of our senses is known to us by a set of attributes … which we arbitrarily combine … and whose own individual existence we accept unquestioned … The Buddha wants Subhuti to look beyond his physical and spiritual bodies to his real body, which is free of all attributes, including the attribute of emptiness.”

I have included long quotes to give a flavour of the text. Red Pine provides detailed commentaries and quotes from major Mahayana figures, past and present. Among those, Vasubandhu and Thich Nhat Hanh have suggested that the central teaching is presented in the first five chapters, with the following twenty-seven chapters adding arguments meant to dispel doubts, as well as warnings against potential misunderstandings of the teaching. Chapter 13 includes a narrative of Subhuti’s enlightenment, an emotional experience bringing tears to Subhuti’s eyes. The following chapters are, by and large, a reiteration of the points examined in the early chapters, with Subhuti now able to give enlightened replies to the questions of the Buddha.

The concluding gatha

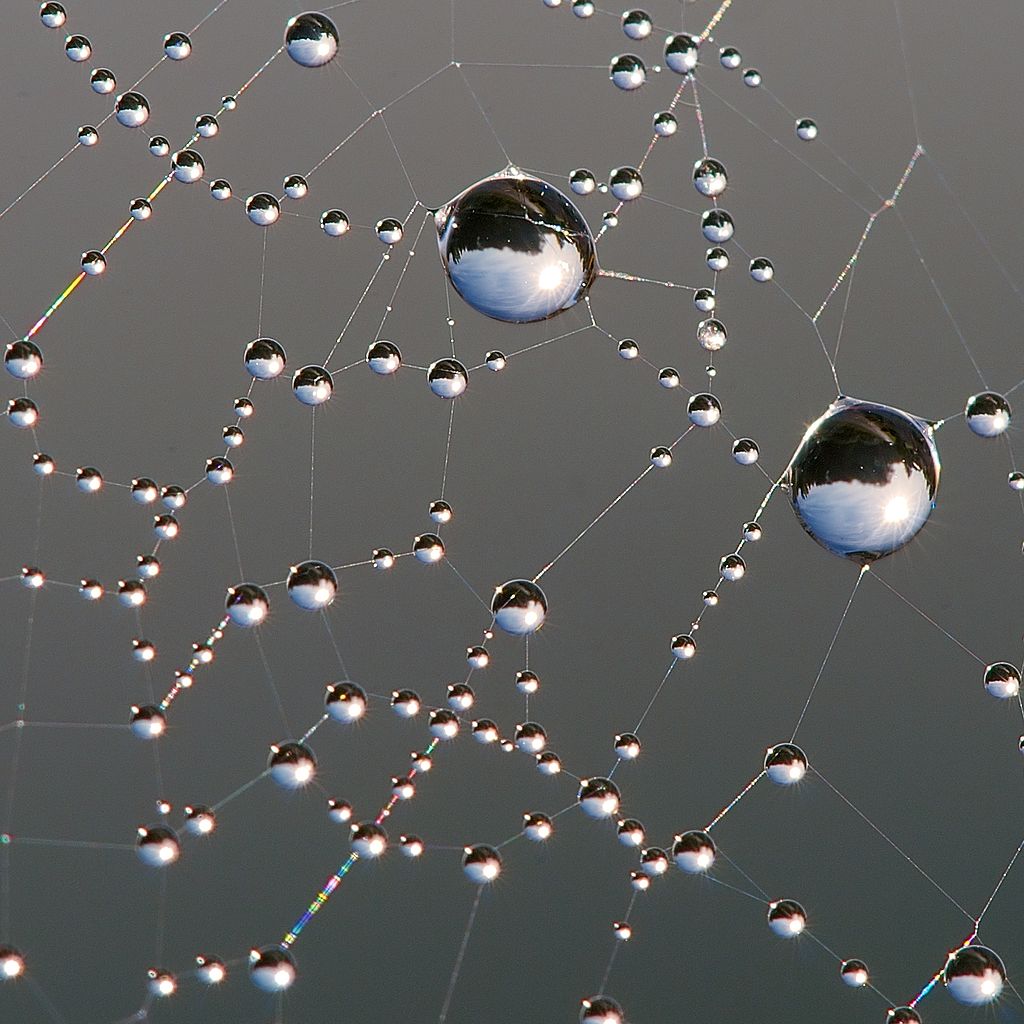

The sutra ends with the famous gatha

“As a lamp, a cataract, a star in space, an illusion, a dewdrop, a bubble, a dream, a cloud, a flash of lighting, view all created things like this.”

Red Pine feels that this gatha does not reflect the gist of the teaching, and argues that it may have been placed here by error, as it is also found at the end of another Prajnaparamitra sutra.

In my view it all depends on what you take to be the intention behind this picturing of reality as dream-like. It could, of course, lead us to see reality as pure illusion. But this interpretation would be at odds with the compassionate vow of saving all beings. As Nagarjuna repeatedly emphasised, it is not that “nothing exists at all on any level,” it is only that things lack “independent existence,” since they arise in dependence upon each other. The above gatha is to be seen as a poetical device to help us free ourselves from our attachments since attachment, Nagarjuna also emphasises, is what makes us super-impose substantiality on things, and keeps us entangled in fixed views of the world. The Bodhisattva’s goal being that of helping others, (s)he will need to break free of received views in order to devise new ways – referred to as “skill in means” (upaya) to successfully liberate other beings. As Hixon puts it, “the via negativa of the Prajnaparamita does not annihilate things; it frees them from entrapment in negativity, opening them up to a creative relativity.”

Instead of dogmatically asserting what is, as in so many sacred scriptures, the Diamond Sutra and other Prajnaparamita sutras spur practitioners to clear up the space so that they can move freely, and unleash their creative spirit.

The Heart Sutra is even more forceful in performing that radical clearing up: “Therefore, Shariputra, in emptiness there is no form, no sensation, no perception, no memory and no consciousness; no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body and no mind; no shape, no sound, no smell, no taste, no feeling and no thought; no element of perception, from eye to conceptual consciousness;no causal link, from ignorance to old age and death, and no end of causal link, from ignorance to old age and death; no suffering, no source, no relief, no path; no knowledge, no attainment and no non-attainment.”

Sources

Paul Williams – Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations 2nd edition (2009)

Red Pine (Bill Porter) – The Diamond Sutra – Texts and Commentaries translated from Sanskrit and Chinese (2001)

Lex Hixon – Mother of the Buddhas – Meditation on the Prajnaparamitra Sutra (1993)

Thich Nhat Hanh – The Heart of Understanding (1988)