Any reference to martial arts in the West brings to mind one or more of the martial arts practiced in Japan – judo, karate, kendo, jujitsu, aikido, etc. – as well as a few having originated in China – taichi, kung fu, etc. While the West has also developed its own martial arts – fencing, wrestling, boxing and swordmanship – no one in fact ever refer to them as “martial arts,” because the term “martial arts” has come to designate something that is more than just ways of fighting. Yuasa Yasuo focuses on this added dimension of Japanese martial arts in his study of the bushi way.

To the list above, Yuasa adds archery and horseback riding, and notes that some of these martial arts originally developed in China – for example, judo, but spread to the rest of the world from Japan rather than directly from China. This, he asserts, has to do with the unique status of the bushi or samurai warriors in Japan.

Contrasting intellectual histories of China and Japan

Even though the West has so far shown more interest in Daoism and Buddhism than in Confucianism,it remains that Confucianism has dominated the history of China since ancient times. Yuasa asserts that “Buddhism and Daoism had been accorded lower status in China”: Daoism because it was seen as a native spirituality with roots in folk beliefs and practices, Buddhism, because it was a foreign import. Yuasa writes: “Confucianism was linked to cultural education such as knowledge of the classics, rites, poetry, calligraphy, and painting, or to use contemporary divisions, to education in the humanities such as philosophy, literature, and arts, which the aristocrats called ‘shitaifu’ (Ch shidafu) were required to study. The shitaifu were aristocrats who controlled political power, holding it both in China and Korea all the way until the modern period. For this reason, the military class was treated as an object of disdain by Confucian aristocrats. It is symbolically epitomized by the phrase, “Respect for Letters, Disdain for the Military [subun keibu] … The martial arts, being mere techniques, have traditionally been regarded … as having a lower value than the classics and the arts.”

Even though the Confucian ethical and political system had been imported to Japan in the early 5th century CE, with Buddhism only entering Japan officially in 552, and had continued to shape the Japanese political institutions for most of its history, a counter-power emerged when “the bushi, or samurai warriors, came to dominate political power toward the end of the Heian period (794-1185),” ushering in the Kamakura period. Since then, and up to the Meiji Restoration in 1868 – that is, for nearly seven hundred years -, Japan was de facto ruled by a military government led by the shogun in Kamakura.

The bushi were expected to educate themselves spiritually

“As a controlling class,” Yuasa explains, the bushi “needed to educate themselves spiritually.” So, “the upper class bushi during the Kamakura period (1185-1333) devoted themselves to the self-cultivation of Esoteric and Zen Buddhism.During the Muromachi period (1338-1573) knowledge of the arts such as waka poetry, linked verse [renga] and the way of tea [sado] were required even of the bushi, whose attitude was epitomized as “Both Ways in Letters and Military” [bunbu ryodo]. Because there was a long period when the tradition of ‘letters’ and that of the ‘military’ interacted in Japan, the martial arts were not simply techniques, but gradually acquired a high artistic sensitivity and spirituality.” “Letters” here refers to religion, scholarship, and the arts, in other words, activities of the mind, whereas the military is an activity of the body. This has led to “‘letters’ and ‘military’, or ‘mind’ and ‘body’, [being] traditionally considered inseparable in Japanese history.” To be sure, a martial art such as taichi in China was already regarded as a way to transform the mind through the body, but this did involve the military takeover of political power. Yuasa, however, states that “The depth of spirituality observed in the Japanese bushi way is a unique cultural product born of the history of Japan … One of the reasons that the Japanese martial arts have attracted the interest of many foreigners lies, I think, in the deep spirituality which the martial arts embody.”

Whereas in China, martial arts developed within the context of Daoism, and expressed their methods in the terminology of alchemy, with words such as dao, qi, yinyang, and the five elements (wuxing), in Japan they were deeply “influenced by Buddhist self-cultivation methods, predominantly those of Esoteric and Zen Buddhism.” Yuasa says that “The theory of the bushi way was formulated at the beginning of the [Japanese] Warring State period (1467-c. 1568), and continued into the beginning of the Edo period (1603-1867).” The bushi way was based primarily on “meditation in motion” (or ‘samadhi’ through continual walking),” and “the goal of the bushi way, in general, is to reach the state of ‘no-mind’ or ‘samadhi’ which opens up through training bodily movement as meditation deepens. For this reason, a center of calm ‘immovability’ (fudo), called ‘no-mind’ or samadhi’, is always found in the midst of bodily dynamism.”

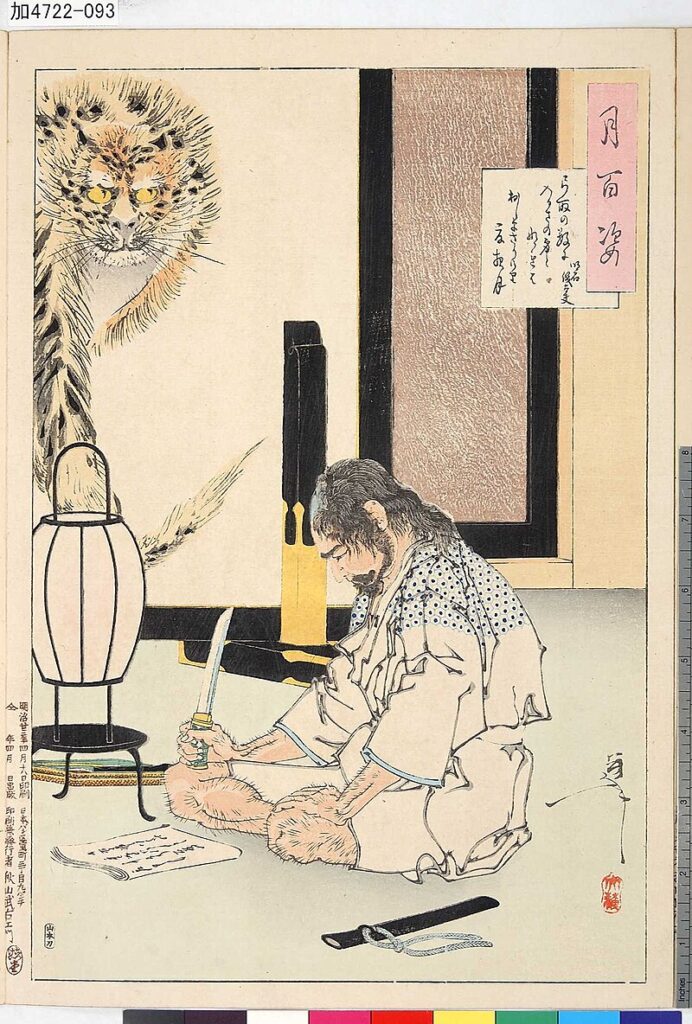

Takuan

Yuasa writes: “Takuan, a Zen monk in the beginning of the Edo period ….explains the mental attitude required by the bushi way.” Takuan calls the psychological state of mind of an ordinary person – that is, an unskilled person – “‘desires riding in ignorance” which is a dark state of living in delusion” and defines it “as a condition in which the movement of mind is captivated by the things before one’s eyes.” Specifically, “If one places his mind on the [opponent’s] sword, the sword will take hold of his mind. If one places his mind on timing, the timing will, again, take hold of his mind. And if one places his mind on his striking sword, that will take hold of his mind. All this is stagnation of the mind and will result in opening up a weak spot before oneself.”(Takuan – Fudochi shinmyoroku)

In contrast, he calls the condition of the skilled master “the immovable wisdom of Buddha.” “It designates a state in which the mind moves freely in all directions, forward, backward, right and left as it wishes without becoming stagnant. Here, the movements of the mind do not remain at any one spot and flow freely. At the center of these movements is “immovable wisdom.” Because the center is immovable, captivated by nothing, the mind can in turn move freely without stagnation.”

The amateur’s state of “desires residing in ignorance” is characterized as “imbalanced mind” [hen shin], “delusory mind” [moshin], and “having a mind’ [u shin].” The skilled master’s “state of “immovable wisdom of Buddha” is described as “‘right mind’ [shoshin], ‘original mind’ [honshin], and ‘no-mind’ [mushin] … Therefore, practice in the bushi way releases one from the mind’s tendency to get fixated and captivated by something, and it trains one to achieve a state of freedom of movement without captivation by anything. If one continues training, Takuan claims, it is possible to reach the “rank of no-mind and no-thought” [mushin munen no kurai]. In the ultimate rank, the hands, legs, and body learn, and the mind does not interfere with anything at all …. the state of conscious movement changes into one in which the hands, legs, and body unconsciously move of themselves. This is the state of ‘no-mind’ … There is an immovable point at the center of the free bodily movements, just as the center shaft of a top maintains a quiet immovable position while it is spinning at full speed. This is what Takuan calls ‘immovable wisdom’.”

Just as “body-mind oneness” can be achieved through waka poetry and Noh theatre, it could be achieved in the bushi way. I would add that it can be achieved in all the “arts”: the tea ceremony, calligraphy, flower arrangement, garden landscape design, pottery, landscape painting, etc. And Yuasa agrees that it can be achieved in the West by an excellent gymnast or figure skater: “If one reaches what is called a perfect performance, one achieves a state in which one can move the body freely without intending it. Here the movements of mind and body are one; there is no distinction between one’s mind and body. To move one’s body without conscious effort suggests that a person is approaching the state of no-mind while letting ego-consciousness disappear.”

But he adds that there is an important difference between western sports and the bushi way: “Training in sports aims at developing the body’s capacity, or more specifically, the motor capacity of the muscles in the four limbs (hands and legs), and does not include the spiritual meaning of training the mind’s capacity.” What this means for Yuasa is that because modern sports focus exclusively on developing the motor capacity of the muscles, it “ignores the problem of the unconscious” whose function “is most clearly manifest in the activity of emotion … “The Buddhist cultivation method of “meditation in motion,” which gave rise to the bushi way, [was] originally designed with the goal of strengthening the synthesis between consciousness and the unconscious by controlling unconscious emotional functions.”

The need to control emotions, Yuasa tells us, is made explicit in the “Heiho kadensho [The Family Transmission of the Military Method], which belongs to the Yagyu school of martial arts.” In this text “original mind” [honshin] is opposed to “deluded mind” [moshin]. “‘Original mind’ refers to the true self endowed in all human beings, corresponding to the Buddhists’ “buddha-nature” [bussho]. In contrast, “deluded mind” is referred to as “I”or as “kekki” [literally, “blood and psychophysical ki-energy]. Kekki refers to an easily agitated mind, and “I” refers to egocentric feeling and emotion ….The “deluded mind” then is that state in which a person is bound to the egocentric movement of the emotions, and is captivated by love and hatred. When it is at work, nothing goes right for a bushi or samurai whether he tries swordsmanship, archery, or horseback riding. The Heiho kadensho maintains that practice in the bushi way aims to overcome the activity of the deluded mind and endeavors to actualize the functioning of the original mind …. The ultimate goal that the bushi way seeks is, as in Zen self-cultivation, the development of a mature personality.”

One must obviously assess this conclusion in the context of the ethos of the time. A training that aims at developing the ability to kill without experiencing any emotion would not be regarded today as the best use of Buddhist practice. Of course, Japan, as an island had to be defended against potential invaders (it had to contend with several attempts by the Mongols), but samurai most often fought on behalf of a damyo wishing to expand its territory at the expense of another damyo. Samurai were expected to commit ritual suicide (seppuku) if they lost a battle.

Yuasa, however, adds: “The sword was originally a weapon … for self-protection or for killing people. It was produced with the purposes of opposing, competing with, or conquering others. However, the ultimate purpose of training in swordsmanship was changed to conquering oneself rather than others. In the Heiho kadensho this transformation is characterized as a change from “the sword to kill others” [satsujinken] to “the sword to save others” [katsujinken]. Aikido, which developed in modern times, was devised by pursuing the implications of this idea to its logical conclusion. Aikido does not aim at competing with and beating an opponent in a match. The term ‘aiki’ designates making one’s ki (psychophysical energy) agree with that of an opponent, that is, bringing about an agreement of the opponent’s body-mind movement with one’s own. To put it more generally, the goal of aikido is to reach a state in which oneself and the other are one through harmonizing and accommodating each other. The martial arts with their initial purpose of opposing and conquering others underwent a change to the technique of conquering oneself, and further to the technique of harmonizing with others so as to become one with them. Here we can discern the important significance of the Japanese bushi way of Japanese intellectual history.”

Sources:

Yuasa Yasuo – The Body, Self-Cultivation, and Ki-Energy

Takuan – Fudochi shinmyoroku (quoted by Yuasa)