It’s important to understand that Absence is not some kind of metaphysical dimension: it is instead simply the empirical Cosmos seen as a single generative tissue, while Presence is the Cosmos seen as that tissue individuated into the ten thousand distinct things constantly giving birth to new things (David Hinton).

National Palace Museum

David Hinton writes: “[Chan, and hence Zen] is most accurately described not as Buddhism reconfigured by Taoism, but as Taoism reconfigured by a Buddhism that was dismantled and discarded after the reconfiguration was complete. This is how China’s artist-intellectual class saw it: Ch’an as a refinement and extension of Taoism.” I feel that it is not so much that Hinton resents the appropriation of Ch’an in Buddhism, but more that, as an outstanding translator of Chinese poetry and philosophy, he bemoans the loss of the true dimension of Chan as “an earthly and empirically based vision.” As he explains, “While the central thrust of Zen practice is to be immediately present in one’s life, rather than living lost in the isolate realm of thought, Zen’s native Taoist/Ch’an framework adds profound and unexpected dimensions to that presence, opening the possibility of weaving consciousness into landscape, earth, Cosmos.”

In China Root and The Way of Chan, Hinton offers an insightful study of the ancient roots of Taoism going back to Paleolithic times, and its flourishing into Ch’an first with the Tao Te Ching and the Chuang Tzu, and later on, with the reinterpretation of these texts by Wang Pi and the school of Dark-Enigma Learning.

Bodhidharma: “Tao is Ch’an”

Hinton writes: “Tao represents one of the most dramatic indications that conceptual Ch’an is an extension of Taoism, because the term Tao is used extensively at foundational levels in Ch’an with exactly the same meaning. In fact, Ch’an practitioners were often called ‘those who follow Tao’, or more literally, ‘those who flow along with Tao’. Bodhidharma states it quite simply: “Original-nature is simply mind itself. Mind is Buddha. Buddha Tao. And Tao is Ch’an.”

“Tao” is generally translated as “Way,” as in “pathway” or “roadway.” “But,” Hinton adds, “Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu … redefined it as a generative cosmological process, an ontological pathWay by which things come into existence, only to be transformed and reemerge in a new form.” Note that here the word “ontological” is not to be understood in its original Greek meaning as the study of “on” meaning “being,” as contained in the “Ideas,” i.e., words, the abstract concepts we use to represent the various parts of reality which Western philosophy has taken as the ground for its mode of thinking. Such notion as a “ground of being” is foreign to Taoism where “ontology” should be seen as the empirical presencing of the ten thousand things out of Absence into Presence. It has been referred to as an “experiential ontology” in both Taoism and the writings of the Kyoto School of Philosophy. Nishida Kitaro, for instance, began his philosophical inquiry with a call to return to “pure experience” which he defined as “the state of experience just as it is without the least addition of deliberative discrimination.”

Hinton explains: “Tao is generally read in contemporary Zen to mean the Buddhist “way” of understanding and practice that leads to awakening – which is sometimes correct, but only sometimes. And “when it is read as the philosophical concept, it is understood as some kind of vague mystical reality, perhaps only available to the awakened. But in fact, “Tao in its philosophical sense is a clearly defined and straight idea that isn’t difficult to understand. And indeed, the failure to understand Tao is perhaps the first and most fundamental way in which the original understanding of Ch’an is lost in contemporary Zen.”

“Presence” as the ten thousand things in constant transformation; and “Absence” as the generative void from which Presence perpetually emerges.”

Even though Lao Tzu spoke of the “emptiness of Tao,” Taoism does not contrast emptiness as absolute truth with the ten thousand things as conventional truth as Nagarjuna did. Instead, Tao is understood in Taoism in terms of Presence and Absence, which Hinton defines as follows: “Presence is simply the empirical universe, which the ancients described as the ten thousand things in constant transformation; and Absence is the generative void from which this ever-changing realm of Presence perpetually emerges.” In the Key Terms listed in The Way of Chan, he says that “a more literal translation of Absence might be ‘without form’, in contrast to ‘within form’ for Presence.” Lao Tzu describes it succinctly like this:

“All beneath heaven, the ten thousand things:

it’s all born of Presence

and Presence is born of Absence.”

The ideogram translated as Absence is that which has been translated in Buddhism as nonbeing (Ch wu – Jap mu) generally said to be mere relative emptiness as compared with sunyata, which is “absolute emptiness.” And it is precisely because wu is an empirical absence, rather than a metaphysical entity as “ultimate reality behind or beyond the physical world we inhabit” that Buddhism regards wu only as a relative emptiness. But, Hinton insists, “this atmosphere of metaphysics is quite foreign to the Chinese sensibility and Ch’an,” noting that “there was no word in Chinese with the meaning of sunyata.” So, Hinton writes: “It’s important to understand that Absence is not some kind of metaphysical dimension: it is instead simply the empirical Cosmos seen as a single generative tissue, while Presence is the Cosmos seen as that tissue individuated into the ten thousand distinct things constantly giving birth to new things.”

A more elemental experience of time

Hinton writes that the generative nature of the Tao “assumes a more elemental experience of time … an all-encompassing generative present that might be described as an origin-moment/place, a constant burgeoning forth in which the ten thousand things emerge from the generative source-tissue of existence: Absence burgeoning forth into Presence” and “inhabiting this origin-moment/place is the abiding essence of Ch’an practice.”

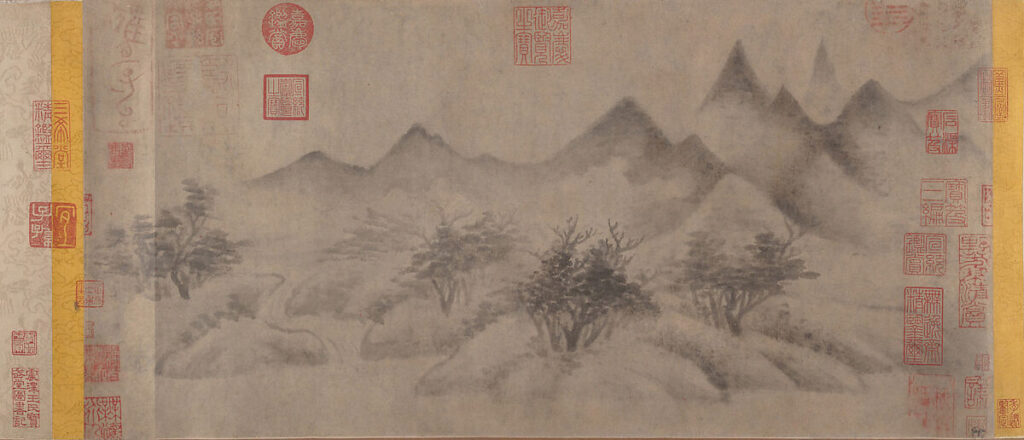

Experientially Tao as an ongoing way is encountered in the cycle of seasons: “Absence in winter, Presence’s burgeoning forth in spring, the fullness of its flourishing in summer, and its dying back into Absence in autumn.” And it is found in “Chinese landscape paintings, an art form that arose with Ch’an historically and was generally considered a method of Ch’an practice and teaching … The empty space in such paintings – mist and cloud, sky, lakewater, even elements of the landscape itself – depicts Absence, the generative emptiness from which the landscape elements (Presence) are seemingly just emerging, or into which they are just vanishing.”

Few works of art exude a tranquility as deep as Chinese mountains emerging out of empty space, often shrouded in mist, but one should not forget the role played by ch’i, the universal life-force in the burgeoning of Absence into Presence. Hinton says that “ch’i is both breath-force and matter simultaneously. Hence, it is nothing other than Tao or Absence, emphasizing its nature as a single tissue dynamic and generative through and through, the matter and energy of the Cosmos seen together as a single breath-force surging through its perpetual transformations.” And because the ten thousand things are the burgeoning of Absence into Presence, rather than substantial entities, Hinton tells us, “There is no distinction between noun and verb in classical Chinese. Virtually all words can function as either. Hence, the sense of reality as verbal: a tissue alive and in process … A noun in fact only refers to a temporal slice through the ongoing verbal process that anything actually is.”

As verbs, Chinese words point to relations within the processual tissue of reality, rather than to static substantial entities that would have subsequently developed relations between themselves. As the formula goes: “the relationship comes before the relata.”

Basically, Hinton explains, “Sage wisdom in ancient China meant understanding the deep nature of consciousness and Cosmos, how they are woven together into a single fabric, for such understanding enables us to dwell as integral to Tao’s generative cosmological process. This is the awakening of Ch’an: “seeing original-nature” … The essence of Ch’an practice is moving always at the generative origin-moment/place, for it is there that we move as integral to existence as a whole.”

In the Platform Sutra, regarded as Zen’s foundational text in the Buddhist presentation of the Zen school, the Sixth Patriarch Hui Neng (638-713 – Prajna-Able in Hinton’s text) – says: “You can see the ten thousand dharmas within your own original-nature, for every dharma is there of itself in original-nature.” The word dharma is the traditional word for “things/events” in Indian Buddhism. Hinton, however, sees here an echo of the early Chinese philosopher Mencius (4th century BCE) who said: “The ten thousand things are all there in me. And there’s no joy greater than looking within and finding myself faithful to them.”

Hinton concludes: “Ch’an recognized it is the presumption of a self that precludes our dwelling as integral to Tao’s generative cosmological process, for self as identity-center is the structure that isolates us as fundamentally separate from the world around us. In that dwelling, we identify not with an isolate identity-center self, but with Tao in all its boundless dimensions. This is an understanding that begins with Lao Tzu, for whom liberation from the isolate self reveals the true nature of self as integral to the cosmological process of Tao: ‘If you aren’t free of yourself / how will you ever become yourself’.” For him, “In that liberation, altogether different from Buddha’s transcendental extinction of self in nirvana, we find a radical freedom that is the focus of both Taoist and Ch’an practice.” I would rather say that, while talk of nirvana is ubiquitous in Indian Buddhism, it is rare, if not absent, from Dogen’s teachings where the individual self – the identity-centre – must be dropped to realise one’s “true self” – the world, i.e., Tao. And this is only one of Daoist Chan’s insights that Dogen brought back from his Chinese teacher Rujing, and integrated with his own teaching. So while it is true that Daoism drastically altered Indian Buddhism, it should also be said that Japanese Zen does teach the original Daoist understanding of Ch’an, but without being aware of its origins in Daoism.

Sources:

David Hinton – China Root – Taoism, Ch’an, and Original Zen

David Hinton – The Way of Chan – Essential Texts of the Original Tradition