As for the Way, the Way that can be spoken of is not the constant Way;

As for names, the name that can be named is not the constant name.

The nameless is the beginning of the ten thousand things;

The named is the mother of the ten thousand things.

Therefore, those constantly without desires, by this means will perceive its subtlety.

Those constantly with desires, by this means will see only that which they yearn for and seek.

These two together emerge;

They have different names yet they’re called the same;

That which is even more profound than the profound –

The gateway of all subtleties.

(Translation by Robert Henricks)

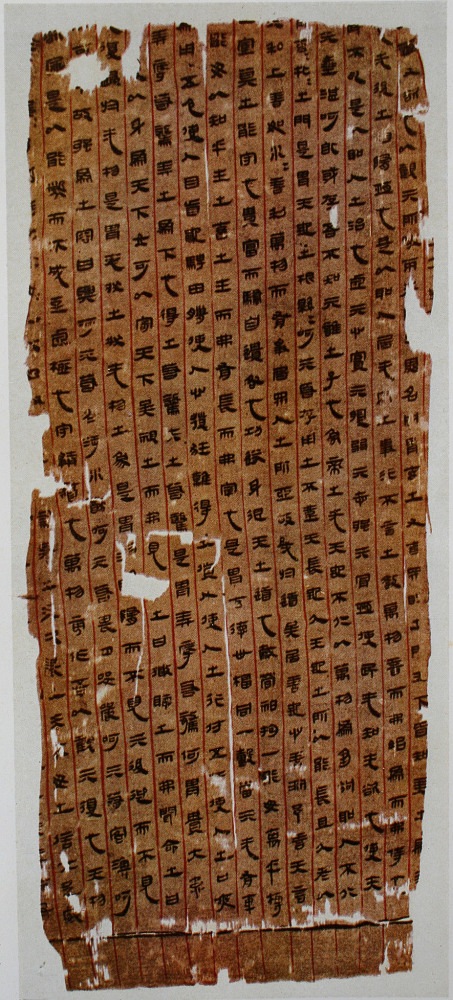

I have chosen Robert Henricks’s translation titled Te-Tao Ching, as a reference because it is based primarily on two of the Silk Texts that were buried in the Ma-wang-hui tomb in 168 BCE, and discovered in 1973. Lao-tzu’s text, when not referred to simply as the Lao-tzu (Laozi), is best known as the Tao-te-ching (Daodejing). The closest translation would be “The Way and the Power.”

Henricks writes: “The Way is Lao-Tzu’s name for ultimate reality (though he continually points out that he does not know its true name, he simply calls it the Way). For Lao-tzu, the Way is that reality, or that level of reality, that existed prior to and gave rise to all things, the physical universe (Heaven and Earth), and all things in it, what Chinese call the ‘ten thousand things’ (wan-wu). The Way in a sense is like a great womb: it is empty and devoid in itself of differentiation, one in essence; yet somehow it contains all things in seedlike or embryo form, and all things ’emerge’ from the Tao in creation as babies emerge from their mothers.”

A Tale of Two Commentaries

Although in the organised religious movement based on the teachings of the Tao-te-ching, Lao-tzu is regarded as a man who lived in the 6th century BCE and met Confucius, scholars now agree that the author of the Tao-te-ching stands for a number of unknown sages who lived much later, whose teachings were gathered into the texts that were discovered recently in the Ma-wang-hui and the Guodian tombs, respectively dated to 168 BCE, and before 300 BCE. Lao-tzu as a man is only known to us through legend, and the lives and teachings of the sages now regarded as the authors of the book are unknown, so scholars have turned to two commentaries – the earlier one by Ho-shang Kung (Heshang Gong), whose name means “Old Master by the River,” who lived in the first century CE, i.e., during the Han dynasty, and, the later commentary of Wang Pi (Wang Bi), a philosopher and politician who lived during the Three Kingdoms period that followed the Han dynasty. Wang Pi’s commentary is generally preferred to Ho-shang Kung’s, but it could well be that the earlier commentary more closely reflects the thought of the collective of authors who composed the Tao-te-ching. So I will present both interpretations, as provided for us by Alan Chan in “A Tale of Two Commentaries.”

Ho-shang Kung’s “Referential Commentary” – The Tao as the Way of Naturalness and Long Life

“As for the Way, the Way that can be spoken of is not the constant Way;

As for names, the name that can be named is not the constant name.

Even those who know nothing about the Tao-te-ching, may have heard these often quoted lines, and have probably found them rather cryptic! For Ho-shang Kung, however, they were not. Alan Chan explains that they refer to “particular objects in nature,” or “specific historical experiences, including events and persons of the mythological past.” This is why he says that, unlike Wang Pi’s more philosophical commentary, Ho-shang Kung’s is “referential” and translates into a network of “correspondences” which delimits the boundaries of interpretation” For Ho-shang Kung, “the “constant Tao” means “the way of naturalness and long life.” By identifying the precise reference, the meaning of the original is rendered concrete and specific. This brings into view also the practical significance of Taoist teachings … Self-cultivation is important, but, ‘the way of naturalness and long life’ does not exclude politics; on the contrary, it offers a superior guide to government.”

Chan also describes Ho-shang Kung’s commentary as a “cosmological interpretation of Tao.” Yet, it is said that “the ‘constant’ Tao is transcendent and thus ineffable.” How can Tao refers to any concrete entity if it is “nameless”? Aren’t names words that have been superimposed on the undifferentiated whole in order to refer to the many “things” that make up the world as we see it in our everyday lives?

The Tao as the beginning of the ten thousand things

The nameless is the beginning of the ten thousand things;

The named is the mother of the ten thousand things.

The third line of chapter 1 describes the nameless Tao, as “the beginning of the ten thousand things.” Chan explains that, for Ho-shang Kung, “nameless” means “without shape or form.” It has no shape or form because it is a dynamism, the vital energy of ch’i. Chan writes: “The Tao” emits the vital energy [ch’i] and gives rise to change. As a result, heaven and earth came into being, and by virtue of the power of life they have received, they in turn produced the ‘ten thousand things’, that is, all beings. Like a ‘mother’, as the Lao-tzu suggests, [here and also in chapters 25 and 42], the Tao not only created the world but nourishes it with its powerful energy.” Thus, Chan adds, “By means of what may be called a cosmological turn, the concept of Tao is connected with the genesis of the cosmos. The claim of transcendence is not undermined; it is, however, interpreted from the perspective of the Tao’s creative power.” Chapter 40 states that “All beings are born of nonbeing … The emptiness of Tao … properly understood, is but another way of affirming the fullness of the vital energy.” As in both texts found in the Ma-wang-hui tomb the section on “te” – power – (chapters 38 to 79) comes first, followed by the section on “tao” (chapters 1 to 37), it could well be that Ho-shang Kung’s description of the relation between Tao, the One, and the ch’i does reflect the views of the sages who composed the Tao-te-ching.

As for the Tao envisioned as the Mother of the ten thousand things, it should not come as a surprise, even for us who live in cultures where God is normally referred to as male. We have all heard the words “Mother Nature.” In early Chinese culture, as in pre-literate cultures, it made sense to understand creation as pro-creation, and postulate a Mother Goddess, rather than a Creator God constructing reality the way a craftsman would make an object, or an architect design the plan of a house. Henricks writes: “That the Tao is a feminine reality and maternal reality thus seems clear. It is not surprising, therefore, that Lao-tzu refers to the Tao as the “Mother” in no less than five places – in chapters 1, 20, 25, 52 and 59. “Other key chapters in the text on the nature of the Tao are chapters 6, 14, 16, 21, 25, 34, and 52.”

Henricks indicates that the selfless “mothering” of the Tao is best described in chapter 34 of the text, although less clearly in the Ma-wang-tui version of the text than in the Tao-te-ching’s standard form: in the latter (Wing-tsit’s translation) it says that [The Tao] “accomplishes its task, but does not claim credit for it. It clothes and feeds all things but does not claim to be master over them,” whereas in the Ma-wang-tui text it says that “it accomplishes its tasks and completes its affairs, and yet for this it is not given a name (meaning ‘makes it famous’). The ten thousand things entrust their lives to it, and yet it does not act as their master.”

Wang Pi’s Hermeneutic Commentary – The Tao as Nonbeing

Chan writes: “Best known in the West as a leading proponent of “Neo-Taoism,” Wang Pi (226–249) is remembered in Chinese sources as a brilliant interpreter of the Lao-tzu and the Yi-ching, and a founding member of “Profound Learning,” hsuan-hsueh. The word hsuan – literally, a deep, dark red color – is taken from the Lao-tzu to signify the profundity or “mystery” of the Tao. Drawing from the Taoist classics and building particularly on the concept of “nonbeing” (wu), Profound Learning is credited – or discredited … for having challenged the Confucian orthodoxy. Wang Pi and others “expounded on the Lao-tzu and Chuang-tzu, and established their root in nonbeing … It gained wide currency and consequently, “Lao-tzu and Chuang-tzu came to occupy the main road, and competed with Confucius for the right of way.”

Wang Pi’s short life – a mere 23 years (it is said that he died from an epidemic) – followed the fall of the Han Dynasty, which had seen the first Buddhist texts being translated into Chinese. Even though it was still early days for Buddhism in China, one cannot rule out a Buddhist influence in Wang Pi’s focus on the concept of wu (nonbeing). Chan also points out that Wang Pi did not see himself as a sectarian Taoist, but simply as a student of Tao, which both Confucians and Taoists put at the very centre of their worldview. Chan says: “He aimed only at ‘broadening the Way’ by bringing to light its full meaning. There is ultimately only one Tao, although articulated differently by Confucius, Lao-tzu, and other ancient sages.” Chan also notes that “Wang Pi not only put forward a new interpretation [of Tao], but spearheaded a fundamental critique of Han learning.”

For Wang Pi, Chan continues, “the Han approach is fundamentally wrong because it fails to recognize the reality of ideas. By reducing meaning to reference, it is in effect denying that written works have a ‘world’ of their own. This can only lead to a fragmented reading … Wang Pi is adamant that words and images can hinder understanding if they are turned into icons with pre-established meanings extraneous to and independent of the texts themselves. They must be ‘forgotten’ in the sense that understanding is possible only if one can, as it were, read between the lines to penetrate into the worlds of ideas that breathes life into the words and images …Those who keep only to the words have not attained the image; those who keep only to the images have not attained the meaning … Reference is not the issue; more critical to understanding is the sense in which the image expresses a deeper idea, and idea which in this instance Wang Pi goes on to relate to “naturalness.” There is no better description of an hermeneutic approach to the texts.

Wang Pi is not concerned with either longlife or cosmological and religious details, Ho-shang Kung’s referents. “Wang Pi consistently directs attention to the Tao itself.” In chapter 33, the image that “one who dies does not perish” (chapter 33) is seen to express the central idea of the limitlessness and inexhaustibility of Tao: “Although one dies, the Way by which life is made possible does not perish.” In chapter 6, Chan tells us, “The “spirit of the valley” discloses to Ho-shang Kung a map of the spiritual body and a guide to naturalness and long life. For Wang Pi, the words bring to mind rather the image of ‘the middle of the valley’, which suggests the idea of ‘nonbeing’ or ‘nothingness.” Once the chains of reference are broken, the commentator is free to pursue the perceived deeper meaning of the text. Together, nonbeing and naturalness for the twin foci of Wang Pi’s Lao-tzu commentary.”

So how did Wang Pi understand the first four lines of chapter 1? The short answer is “as nonbeing, wu”. Chan writes: Grammatically, the word functions both as a transitive verb and as a noun. Wu and its opposite yu mean basically “not having” and “having” something, and “nothing” and “something”. Disagreement, however, arises when they are extended to represent metaphysical concepts. If wu means “nothingness” or, as many scholars prefer to translate “nonbeing,” does it have a positive meaning, or even reference? In Ho-shang Kung’s commentary, it is viewed positively in terms of ch’i energy. Even if “nothing” can be seen or described, “something” is certainly there to bring about created order. Can the same be said of Wang Pi’s understanding? Inasmuch as yu is most simply rendered “being” at the ontological level, wu may be translated as nonbeing. This does not, however, prejudge its meaning or rule out other translations.”

In Wang Pi’s words: “The Way that can be spoken of and the name that can be named point to things and represented forms, which are not constant. Hence (the constant Tao) cannot be spoken and cannot be named.” Both commentators recognise the transcendence of Tao, but, Chan says, “Unlike Ho-shang Kung, Wang Pi is not concerned with what the constant Tao stands for, but with the logic of Lao-tzu’s argument. The same approach marks his understanding of Tao as the “beginning” and “mother” of all things.” Remember that for Ho-shang Kung, the Tao was the “One,” that is, ch’i, the vital energy that originates and nourishes the ten thousand things. Quoting chapter 51, Wang Pi writes: “All beings originate from nonbeing. Thus, before there are forms and names, the Way then is the “beginning” of the ten thousand things. When there are forms and names, the Way then “brings them up, nourishes them, makes them secure and stable”; it is their “mother.” This means that the Way in its formlessness and namelessness originates and completes the ten thousand things. They are thus originated and completed, but do not know why this so.” Wang Pi’s point is that the ten thousand things arise “logically” (though paradoxically) out of the Tao as nonbeing, rather than produced by ch’i in the way things are produced in the world around us.

Chan writes: “The transcendence of Tao is to be affirmed on account of its formlessness and ineffability. But in relation to beings, the Tao is conceived as both absolute beginning and teleological end. The latter, an extension of the idea of an overarching presence and purpose of Tao, makes possible the transition from metaphysics to ethics … The theme of transcendence is linked directly to the inadequacy of language and its implication for understanding. “Names,” Wang Pi states, “serve to determine form. Completely undifferentiated and without form, the Way cannot be pinned down and determined (ch 25). Although such words as “deep,” “wondrous,” and “great” may be useful in providing glimpses of the Tao, “they do not exhaust the meaning of the ultimate.” Even the word “Tao” is to be used with caution and not turned into a divisive and limiting “name” (ch 25). Indeed, “If one speaks of Tao, one loses its constancy; if one were to name it, one misses its truth.”

Desire as the root-cause of words

Therefore, those constantly without desires, by this means will perceive its subtlety.

Those constantly with desires, by this means will see only that which they yearn for and seek.

This reminds me of the second and third noble truths in Buddhism: ‘Craving is the origin of suffering. Freedom from craving is the cessation of suffering.”

Those who are familiar with Iain McGilchrist’s hemisphere theory will have no trouble understanding Lao-tzu’s reference to “desires” as the root-cause of the differentiation of the one undivided whole into the ten thousand things. McGilchrist associates the origin of concepts to the need to focus narrowly on “things” we “desire” and want to grasp, we inherited from our animal ancestors which needed to feed while at the same time remaining broadly aware of what was happening in their environment, in order to remain safe from predators. He then ascribes the narrow focus to the view of the left hemisphere of the brain, and the broader awareness to the right hemisphere. Whether or not the desire corresponds to a need is secondary, it is the desire, the narrow focus on what they want to grasp, that for humans triggers the creation of “the ten thousand things,” the many fragments that ends up obscuring the flow of interpenetrating phenomena that constitutes reality.

The One and the Many

These two together emerge;

They have different names yet they’re called the same;

That which is even more profound than the profound –

The gateway of all subtleties.”

Having connected with the whole does not, however, imply for the sage that (s)he no longer sees the ten thousand things! The sage is he/she who has learned to live without desires in the midst of a dynamic world, that is a Way, or, as some scholars now call it, a “waying” – a verb rather than a noun – empty of fixed (ontological) entities, but moved by ch’i, the vital energy, itself resulting from the interplay of yin and yang, while, of course, remaining aware of the division of this world into the “ten thousand things.” As I understand it, as long as desires are present, we will use yinyang as a tool to manipulate the ten thousand things. To be a “sage,” however, we need to be desireless, as only then can we embrace the naturalness of reality in all its “subtleties,” as well as, respond spontaneously (wuwei) to whatever arises in our lives.

Sources:

Robert G Henricks – Lao-Tzu, Te-Tao Ching

Alan K L Chan – “A Tale of Two Commentaries: Ho-shang-kung and Wang Pi on the Lao-tzu in Lao-tzu” and the Tao-Te-Ching, ed. Livia Kohn and Michael Lafargue