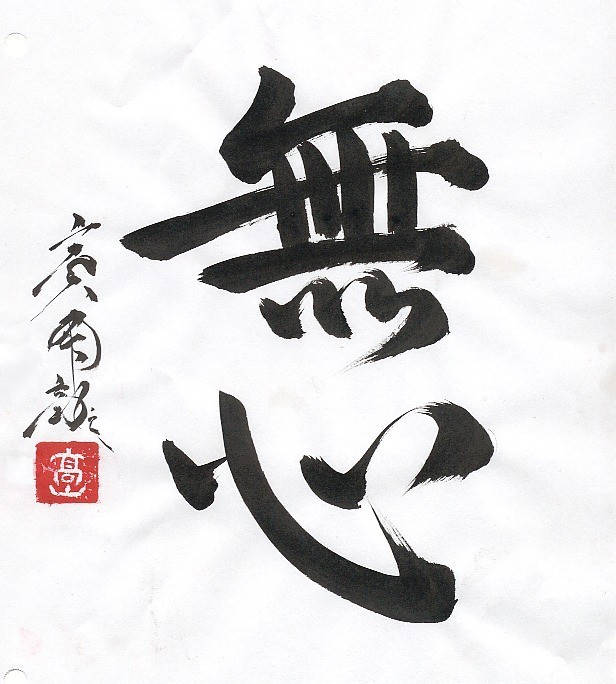

“The word “mushin” already existed in the Daoist philosophy before Buddhism was transmitted to China. And of course, the word “mushin” can also be translated using words derived from Indian Buddhist philosophy. For example, there are compound words such as anatman (the absence of ego), acitta (the absence of a soul) stemming from “no” and “mind.” However, when Chinese Zen began using these words with a special meaning attached to it, it came to mean ‘the state of freedom wherein one is liberated from attachment’ as the ‘union between non-action in harmony with the Dao (wuwei ziran) and Buddhist wisdom’” (Nishihira Tadashi).

In the first chapter of The Philosophy of No-Mind, Nishihira Tadashi reviews the history of the meaning of “mushin” in both Japan and China. Starting with Japan, he says that, in ancient Japan, the meaning of mushin was equivalent to that of kokoronashi, “mindless,” or “heartless,” used in a disparaging fashion to refer to someone being “thoughtless, inconsiderate, lacking in refinement, or insolent … all insulting descriptions.” He quotes the early Kamakura poet Kamo no Chomei (1155?-1216) as saying “A mindless woman reciting poetry is often lacking in skill.”

However, he also notes that the near-contemporary Buddhist itinerant preacher Ippen Shonin (1239-1289) explicitly referred to mushin (no-mind) as superior to ushin (having mind) when he wrote “Ushin is the way of life and death, mushin is the castle of nirvana.”

Dogen (1200-1253) himself, while not actually using the word mushin had also alluded to a mushin-like experience in one of his poems:

“The body without mind,

Listening to the rain

Becoming one

With raindrops from the eaves.”

Dogen here uses the words “body without mind” as “listening from a state of no-mind (the rainwater from the eaves are my own self) even though, Nishihira argues, “it is hard to believe that Dogen was unaware of the traditional meaning of “without mind” in a waka by Saigyo (1118-1190), where it means “unrefined.”

Nishihira then retraces the ascendancy of mushin over ushin in Japan during the following centuries. He identifies Zeami (c.1363–c.1443), a Noh master of the Muromashi Period, as the man who, not only used mushin as superior to ushin, but delved deeper into its meaning while using it in the context of the training of Noh actors. In his Performance Notes he uses the word mushin to designate “a special state wherein primordial freedom and spontaneity (jizai) is possible.” Nishihira further explains: “Zeami emphasized care in practice. All the movements of the body should be conducted with care. However, immediately after that, he also said that as long as there is care, one does not arrive at the greatest artistic performance … The highest state is when there are no longer any cares. To perform with abandon, without calculation. At each time and place, whatever needs to be done comes to you. And accepting things as they are, you perform as if things arose spontaneously. At that moment, one is not negating, but rather accepting things as they are. That highest level is called “the place of no-mind.”

No entry for “mushin” in the Mochizuki Buddhist Dictionary

Nishihira then turns to the Mochizuki Buddhist Dictionary, and expresses his surprise that “it does not have an entry for mushin.” Neither can he find one in the Dictionary of Zen Thought.” To be clear, he adds, mushin “can be seen in the Buddhist dictionary as a word; however, it is not recognized as being on the same level as dhyana-samadhi (meditative concentration), samatha-vipasyana (calm abiding and clear observation), and empty mind, which are clearly Buddhist terms. Perhaps mushin is too catch-all to be used as a technical term. In contrast, that is probably why it is used so handily in everyday life. Everyone knows it, and it is often used in introductory books.” However, “as a specialized Buddhist term, the word mushin has a precarious position.”

Nishihira does note that Yogacara (or “Consciousness-Only”) philosophy talks about “two samadhis without thought [mushin]” in the Trimsika-Trimsika-Vijnaptimatrata:

“The thought consciousness always manifests

Except for those born in the heavens of no-thought,

For those in the two samadhis without thought [mushin],

And for those in drowsiness or unconsciousness.”

He comments: “In the text, “the two samadhis without thought” refer to musojo and metsujinjo. In musojo, the five senses cease functioning and images no longer arise in the heart-mind, but the mana consciousness is still working. That means that there is still some ego consciousness that remains. In contrast, metsujinjo is a state of dhyana where even the attachments within mana consciousness are completely extinguished. Thus, it is the state wherein the workings of ego consciousness have completely ceased. However, in both cases, the deepest layer of consciousness, the alaya-vijnana (store-house consciousness), is still thought to be working, so dhyana must go deeper into this.”

From this, Nishihira concludes that “even though the word mushin appeared in Buddhist thought even before Zen, it was not a technical term with a clear definition. Rather, it was just a generic term whose details were explained by even more technical terms.”

Japanese “mushin” as mindless/unrefined and Daoist “mushin“ (wuxin) as two unrelated streams

Nishihira then explains that the ancient Japanese meaning of “mindless” (kokoronashi) to mean “unrefined” and “mushin as used in Chinese Zen (Chan) parlance to mean being free of attachments, were originally unrelated. Nevertheless, because the same Sino-Japanese characters and the same pronunciation were used to refer to both, this gave rise to confusion and ambiguity. A reversal arose in the same word.” So, “originally, the two streams did not have anything to do with each other.” It is only because the same word was used for both that confusion arose.

Roots of “mushin” in Chinese Daoism

Nishihira writes: “In mainland China, Daoist thought spoke of mushin even before Buddhism was introduced. For example, let us look at Zhuangzi. In a passage (read in Japanese as “Mushin erarete kishin fukusu”) that can be understood as meaning “When not even a trace of greed is left, even the divine spirits will give admiration,” the mushin which even divine spirits will acknowledge is the state of freedom wherein one is not captured by anything. It means “emptying one’s mind and mingling and frolicking in the world. It can also be paraphrased as asobigokoro (a playful heart). Or, in the sense of “emptying one’s mind and waiting for things,” to move in accordance with the movement of things, and because one is in a state of mushin, the [acting] subject remains unchanged.”

It is well attested that, when Indian Mahayana thought entered China, it was initially understood through the filter of Daoism, specifically Laozi and Zhuangzi, and this, in time, Nishihira asserts, “gave birth to Zen.” In that sense,” he says, “the early stage of Zen thought is Buddhist thought that was influenced by the Daoist idea of mushin. With Zen, for the first time, Chinese Buddhism became an indigenous ideology (rather than an imported one).

Furthermore, according to studies which compared the mushin of Zhuangzi and the mushin of Zen, there are some similarities between the two. For example, they share the idea of living freely, not being caught up by anything, or the understanding that fundamental reality (called Dao, the way, by Zhuangzi, and jishin honbutsu – True Self, or the primordial Buddha – in Zen) cannot be grasped through discrimination (telling apart this or that); rather, discrimination actually damages reality. Added to that in both views, by negating discriminating knowledge, one returns to an everyday life that affirms everything, and this everydayness is emphasized along with a respect for the ordinary.”

However, Nishihira adds: “research also pointed out decisive differences. While Zen has the philosophy of emptiness at its foundation, Zhuangzi does not. Zen stresses a skeptical concern for impermanence, bad karma, and attachments, but Zhuangzi does not. While Zen distances itself from Being, Daoism immerses in it. It was also pointed out that the mushin of Laozi and Chuang Tzu means to be immersed in things and acting with them, but the mushin of Zen means a contemplative distancing from things. But, “without confirming the meaning of mushin in Zen, we have no way of deciding if these views are right.”

Furthermore, Nishihira says that the “mushin of Bodhidharma and the mushin of Mazu have very different flavors. Because of this, in the understanding of this book, it would be impossible to lump these into one understanding of the “mushin of Zen.” Issues raised in the first chapter are discussed in more depth in the other nine chapters of the book, where Nishihira includes reviews of the conclusions found in the scholarship of D T Suzuki, Izutzu Toshihiko, Zeami, Takuan, and Ishida Baigan.

In addition to the issue of the meaning of mushin for the Japanese, there are additional difficulties related to the translation of mushin into English. For instance, in Eugen Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery, mushin is translated as “unintentional.” “Examples of the usage of ideas similar to mushin include “to forget all desires and ambitions,” “to transcend one’s worldly self,” or “without worrying about the outcome.”

Nishihira concludes the chapter with the following lines:

“The word mushin already existed in the Daoist philosophy before Buddhism was transmitted to China. And of course, the word mushin can also be translated using words derived from Indian Buddhist philosophy. For example, there are compound words such as anatman (the absence of ego), acitta (the absence of a soul) stemming from “no” and “mind.” However, when Chinese Zen began using these words with a special meaning attached to it, it came to mean “the state of freedom wherein one is liberated from attachment” as the “union between non-action in harmony with the Dao (wuwei ziran) and Buddhist wisdom.”

Source:

Nishihira Tadashi – The Philosophy of No-Mind – Experience Without Self