“The Cloud encourages abandoning thought so as to reach a state of unknowing in which one may commune with the divine. This “cloud of unknowing,” as the writer calls it, is referred to as a darkness that is between you and God stopping you from seeing the divine clearly and directly.”

(Tim Langdell)

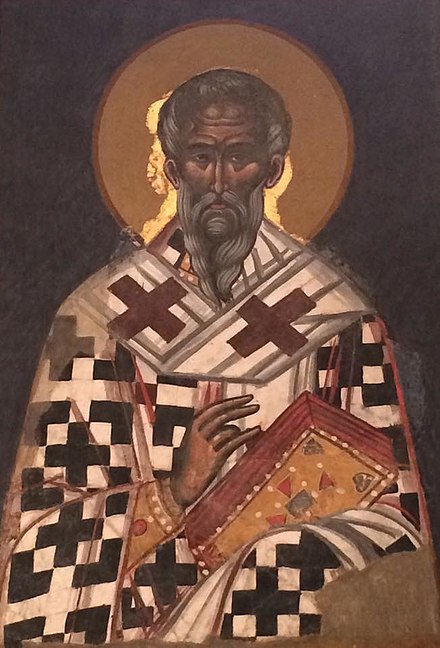

While Jesus’ own teachings were, for ordinary Christian believers, obscured by the mistranslation of metanoia as (moral) repentance, which placed sin, and the fear of Hell, at the centre of the creed taught in the churches, a rich apophatic tradition developed during the Middle Ages, starting with the Church Fathers, followed by Gregory of Nyssa, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, Meister Eckhart, Nicholas of Cusa and Angelus Silesius. These mystics were aware of the original meaning of metanoia as a transformative experience, and fulfilled Athanasius’ words, whereby “[Christ] was made human so he might make us sons of God.”

For various reasons – the persecution of “heretics” by papal authorities during the Inquisition from the 12th to the 19th centuries, as well as the growth of materialism in the West from the 18th century onwards – Christianity came to forget that it had a mystical tradition. When Buddhism moved West in the 1960s, Christians realised that something was missing in their faith, and this realisation quickly crystallised around the lack of a specific practice that would make it possible for them to gain the equivalent of Buddhist awakening. A few became acquainted with Buddhism, especially Zen, and practiced Zen meditation. Among these, Fr Thomas Keating, a Cistercian monk worked out a new Christian form of contemplative prayer he called Centering Prayer by combining ideas he found in Dionysius’ ideas as reflected in the Cloud of Unknowing, and meditation techniques borrowed from Zen. Additionally, Tim Langdell himself further developed another form of contemplation, which he called Kenosis or Kenotic Meditation, originally inspired by Centering Prayer, but, in his view, more likely to lead to a transformative experience.

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and the Cloud of Unknowing

Langdell writes: “Pseudo-Dionysius was an anonymous Christian philosopher active around late 600 to early 700 CE known for a set of works, the Corpus Dionysiacum. He took his name from the Athenian convert “Dionysius” who Paul mentioned in Acts 17:34 – hence he added the term “pseudo” since he was not alleging that the author of the works was that actual person mentioned in Acts.”

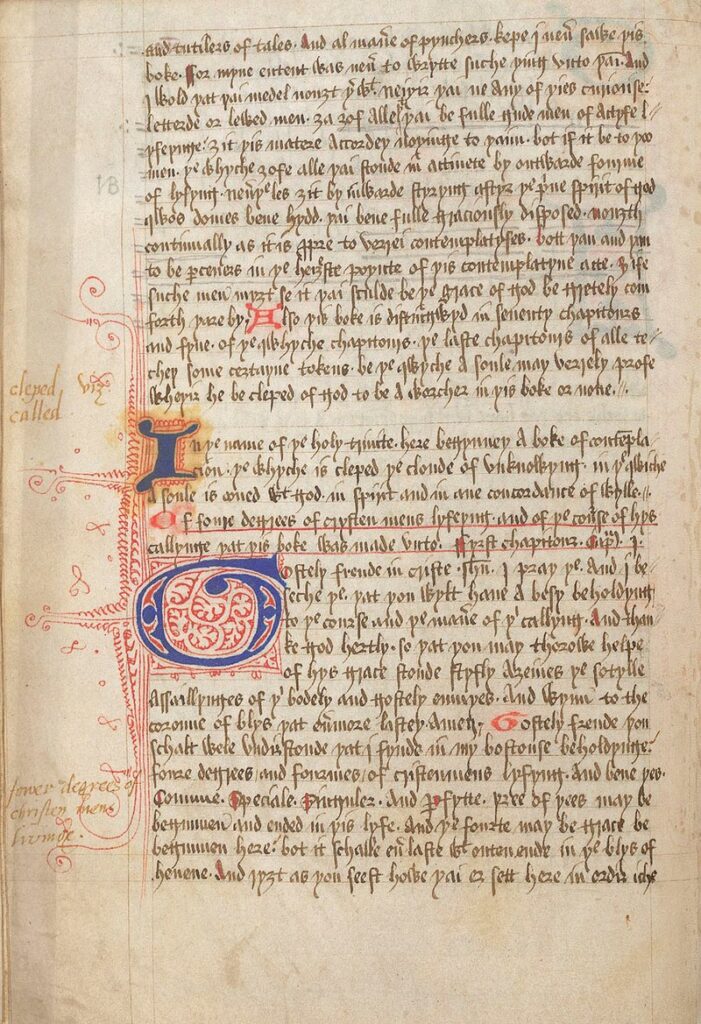

The Cloud of Unknowing is an anonymous work written in the 14th century on the topic of contemplative prayer. It is based on “the mystical writings of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, specifically, and on Christian Neoplatonism generally.”

“Pseudo-Dionysius emphasized the importance of both ways of approaching understanding or appreciation of the divine. He saw the kataphatic approach as an affirmative way of understanding transcendence using positive attributes, and the apophatic way as stressing God’s absolute transcendence and unknowability.” Apophatic theology is also known as the via negativa and, Langdell notes, is “often associated with mysticism and mystical experience. It is a way that realizes that ultimate truth cannot be described in words. Hence, this approach is associated with reports of experiences of oneness with God, or oneness with everything (to use non-mythological language) rather than intellectual description or speculation about the nature of God or oneness with God. The use of words, and in particular, the converse kataphatic theology (or cataphatic, positive way), seeks to describe the ultimate reality using positive attributes such as “God is love,” or “God is good” … Why this is of interest to us here is that what he wrote has parallels with Zen: just as he wrote that it is ultimately important to “understand” God as both imminent (known, named) and transcendent (unknowable), in Zen we have the parallel of the relative (named; dualism) and the absolute (beyond naming or before thought; non-dualism).”

Langdell also reminds us that the word agnosticism was not, at the time, synonymous with “atheism.” It simply meant that “God, the ground of being, or the ultimate nature of reality … is essentially unknowable … This has a direct parallel in Zen to what we refer to as “don’t know mind,” or “beginner’s mind” – the state of being before thought (or beyond thought; we are back again to Jesus metanoia) … Via negativa and agnosis … formed the basis of both the works of Pseudo-Dionysius and the author of the classic text The Cloud of Unknowing.”And they go back to Philo of Alexandria (20 BCE-50 CE) whose ideas had shaped Jesus’ teachings, as well as those of Paul which, through their emphasis on pedestalising Christ as the only ‘Son of God” (evidenced by his resurrection) sowed the seed for a drift towards erecting unsurmountable barriers against anyone wishing to emulate Christ and also become a “Son of God.”

It is clear that we do not have in Christianity a faith that arose from the teachings of a single mystic providing us with the equivalent of the Buddha’s Eightfold Path which would allow us to replicate his quest, and attain what he himself had attained. Instead, in Langdell’s words: “Regarding silent prayer and meditation, we have an arc we can draw from the time before Christ with Platonic ideas and the Stoics, through the works of Philo and the emergence in parallel at this time of Mahayana Buddhism in Alexandria (where Philo was also based), through the Jewish Wisdom tradition of the first century, through practices such as Hesychasm, and on through the Neoplatonist tradition in the centuries that followed, on through to the writing of the Cloud of Unknowing. The Cloud was the ultimate guide to contemplative prayer of medieval times, which was merged with Zen to create modern day Centering Prayer practice and led to the current revival of kenotic practices [which he presents in his book].”

Just like the early apophatic tradition which sought God in a darkness beyond “words” (as staged by the encounter of Moses with God inside a cloud on Mt Sinai, when God appeared to him in his unknowability), Langdell says that “The Cloud espouses a mystical approach to Christianity that sees God as beyond knowing and encourages the follower to abandon the ego to a state of consciousness best described as “unknowing.” If this road is followed, the author suggests, then one may gain a glimpse of the true nature of God, become one with God. Clearly, The Cloud draws heavily on the via negativa school, and has much in common with the earlier apophatic tradition that came about in the time of Christ.”

“We don’t know who wrote The Cloud. It seems fitting that it drew in large part on the works of Pseudo-Dionysius who also remained anonymous. It is open to speculation, but perhaps in both cases the writers feared retribution for writing what some might call heretical works. The Cloud encourages abandoning thought so as to reach a state of unknowing in which one may commune with the divine. This “cloud of unknowing,” as the writer calls it, is referred to as a darkness that is between you and God stopping you from seeing the divine clearly and directly.”

The Cloud “recommends focusing on a single word as a way to entering into stillness and full contemplation.” Specifically, it says: “We must pray, then, with all the intensity of our being in its height and depth and length and breadth. And not with many words but in a little word of one syllable.” Words selected for this are “God” and “sin.” And it “makes clear that this repetition is of a contemplative nature, not the fast-paced repetition sometimes used in Hindu or Muslim chanting.” “Moderation” is recommended and one must adopt “contemplation as central to one’s way of life.” And in chapter 43 the writer “introduces what he calls the “cloud of forgetting”: “Be careful to empty your mind and heart of everything except God during the time of this work. Reject the knowledge and experience of anything less than God, treading it all down beneath the cloud of forgetting” … And now also must learn to forget not only every creature and its deeds but yourself as well, along with whatever you may have accomplished in God’s service.” In Buddhism, the word “forgetting” is associated with Dogen, the founder of the Soto Zen school, who famously said:

“To study the Buddha Way is to study the self.

To study the self is to forget the self.

To forget the self is to be verified by all things.

To be verified by all things is to let the body and mind of the self and the body and mind of others drop off.

There is a trace of realization that cannot be grasped. We endlessly express the ungraspable trace of realization.”

The Cloud follows the exact same path when it talks of “destroying the self (ego)”: “Long after you have successfully forgotten every creature and its works, you will find that a naked knowing and feeling of your own being still remains between you and your God. And believe me, you will not be perfect in love until this, too, is destroyed.”

In addition to Pseudo-Dionysius and The Cloud, Langdell notes that Meister Eckhart and Angelus Silesius must be included in the effort by contemporary Christian teachers to work out both the Centering Prayer and the Kenotic Meditation.

Eckhart wrote: “Unmovable disinterest brings man into likeness of God … To be full of things is to be empty of God, to be empty of things is to be full of God.” (see next page) for more on Meister Eckhart.

Silesius wrote:

“True prayer requires no word, no chant, no gesture, no sound.

It is communion, calm and still with our own Godly Ground.”

“God far exceeds all words that we can here express.

In silence He is heard, in silence worshiped best.”

“Even before I was me, I was God in God;

And I can be once again, as soon as I am dead to myself.”

Langdell missed Silesius’ most famous quote, relevant here as encapsulating Eckhart’s concept of “Living without Why”:

“The rose is without why. It blooms because it blooms.

It pays no attention to itself, asks not whether it is seen.”

Centering Prayer

Langdell writes: “Centering Prayer has its roots in the works of Thomas Keating when he was the abbot of St Joseph’s Abbey in Spencer, Massachusetts from 1961 to 1981. During the latter period of his tenure as abbot he and his fellow monks invited a Zen master to introduce them to the idea of a “sesshin” (week long intensive retreat) and from this, coupled with reviving the ideas in The Cloud of Unknowing, Buddhist Zen meditation evolved into Centering Prayer … To use Fr Keating’s language, he sees Centering Prayer as choosing a word that “represents our intention to consent to God’s presence and action within us.”

“He summarizes the key elements of Centering Prayer thus:

- Choose a sacred word as a symbol of your intention to consent to God’s presence and action within.

- Sitting comfortably and with eyes closed, settle briefly and silently introduce the sacred word.

- When you become aware of your thoughts, ever-so-gently return to the sacred word. The sacred words he suggests include “God,’ “abba,” “Jesus,” and “peace.”

- At the end of the prayer period, remain in silence with your eyes closed for a couple of minutes.”

Langdell feels that Kenosis (or Kenotic Meditation) the type of contemplative prayer he proposes, is “closer to the practice Christ himself used” – as well as closer to zazen – because it is completely silent, and also because the eyes have to remain open (say, half-open) -, and is more likely to help practitioners realise a “metanoia moment.” “Kenosis, he says, “involves a focus on self-emptying, and on being fully present to God in the moment … we do not use words while practicing kenosis. The other aspect that differentiates kenosis from Centering Prayer is the goal of being fully awake in God in the moment, and for this reason we employ all the senses and do not close our eyes. The other reason we do not close our eyes is that this leads to a greater tendency to doze off, have a waking dream, or to just drift.” As it is in shikantaza, the “just sitting” type of zazen practiced in the Soto Zen School, “our goal with kenosis isn’t to stop our thoughts, but as thoughts come up just observe them like clouds and let them float by …” As you sit, the goal can be summed up by “let go and let God.”

What is aimed at in a practice of contemplative prayer, or meditation, is a “forgetting,” (or a “destruction,” or a “sacrifice” or, in philosophical terminology, a “negation”) of the ego-self”, is not a suppression of one’s subjective function, but simply a dis-identification from the representation of this function as the “thing” called “self” – a word, a mere “representation,” in order to access what Dogen calls the “true” self, which is one’s genuine subjective function – a verb rather than a noun – which is one with the cosmos as a whole.

Source:

Tim Langdell – Christ Way, Buddha Way