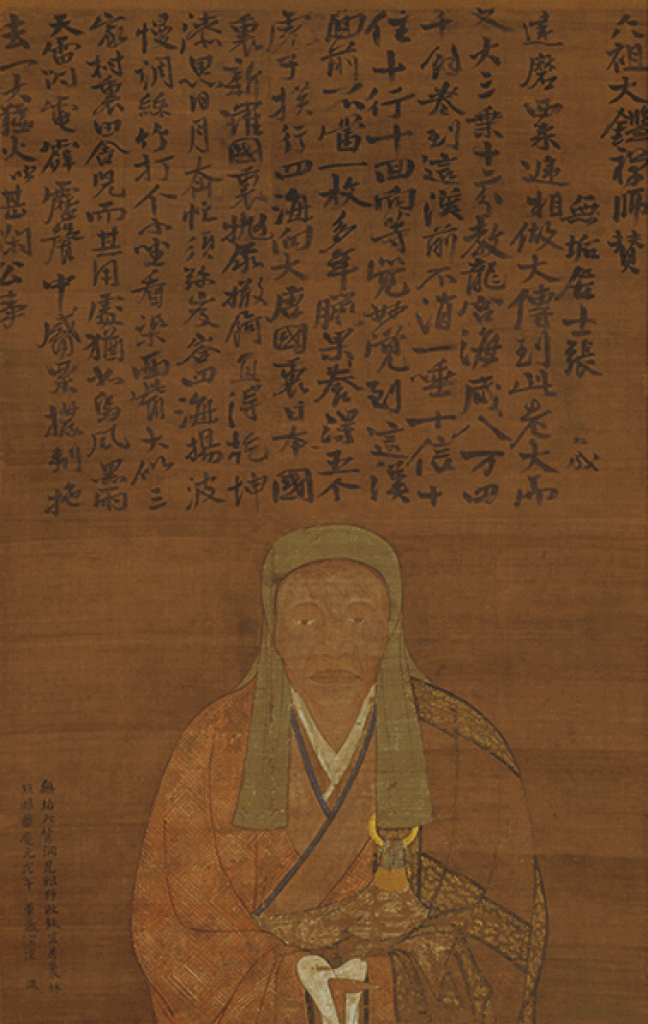

Shofukuji, Fukuoka

Speaking about Huineng (638-713), the Chinese master whose teachings, presented in the Platform Sutra, laid the foundations for the Zen school, Bret Davis writes: “What Huineng calls ‘no thought’ (Ch wunian, Jp munen), and what later is often referred to as ‘no-mind’ (Ch wuxin; Jp mushin), does not exclude thinking; rather, quoting Huineng, ‘no-thought is not to think even when involved in thought … if you give rise to thought from your self-nature, then, although you see, hear, perceive, and know, you are not stained by the manifold environments, and are always free.”

What is meant by “no-mind” is the ability to “flow” with things and events, without “lingering in” any of them. Davis write: “No-mind is akin to what athletes or musicians experience when they are ‘in the zone’, utterly absorbed in an activity of the here and now (including when the ‘here and now’ involves remembering, planning, or otherwise thinking of the ‘there and then’). A Zen master, however, would live all of life in the zone, whether listening or laughing, crying or dying, and would be able to shift effortlessly between different activities, at once absorbed in and yet unattached to any of them.”

Davis argues that this is also true of intellectual activity: “Not only when one is absorbed in a train of thought, also when one effortlessly switches one’s focus from one train of thought to another, this too is an instance of no-mind.” No-mind is not ‘thoughtlessness’. To get a thoughtless mind, you need to deliberately block all thoughts. But then you get a blank vacuum, not a free flow of thoughts. Thomas Kasulis described no-mind as “a heightened state of non-dualistic awareness in which the dichotomy between subject and object … is overcome.”

Sources:

Bret W. Davis – “Forms of Emptiness in Zen” (Research paper)

Thomas P. Kasulis – Engaging Japanese Philosophy (2018)