“I am thinking of making philosophy work as the thinking of basic non-thinking, just like the everyday labor of working the field and pulling the weeds in the mode of “taking the spade in the hand while staying empty-handed,” directly revealing absolute nothingness. From such a standpoint I wish to clarify the many problems of our day” (Nishitani Keiji, “Encounter with Emptiness,” in Taitetsu Unno, The Religious Philosophy of Nishitani Keiji).

A not so happy childhood

Unlike Nishida, Nishitani did not keep a diary, and we do not have for him the equivalent of the detailed biography Michiko Yusa has offered us for Nishida in “Zen and Philosophy.” Biographical information on Nishida was gathered from his Collected Works and personal documents by James W. Heisig, former director of the Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture in Nagoya, and can be found in his Philosophers of Nothingness.

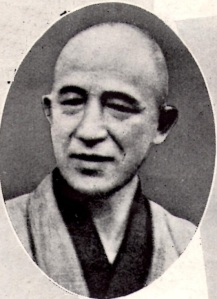

Nishitani Keiji was born in February 1900 in Udetsu, near Noto, in the Ishikawa Prefecture on the Japan Sea, which happens to be in the same region as Nishida’s birthplace. In his book on Nishida, Nishitani recalls the happy moment when the two men realised these shared origins, as, having just graduated, Nishitani had his first private meeting with the rather intimidating Nishida (Nishitani, Nishida Kitaro, 18). At age seven, he moved to Tokyo with his family. When he was fourteen, his father died of tuberculosis, and he himself suffered from the same disease for many years. This caused him to be regarded as physically unfit when he first tried to enter the prestigious Daiichi High School. He was then sent to recuperate in the northern island of Hokkaido, a time he spent reading the novels of Natsume Soseki, where, Heisig tells us, “his attention was caught by references to the Zen state of mind” (183). Soseki’s novels exerted at the time a strong influence on the Japanese intellectuals who found themselves caught between the appeal of Western culture and their attachment to traditional Japanese values. On his return, after a second attempt, he was able to join Daiichi.

Once a pupil there, Nishitani was able to read widely outside the curriculum – Dostoevski, Nietzsche, as well as well as Hakuin, the Bible, and St. Francis of Assisi. This is also the time when he chanced upon Nishida’s Thought and Experience. Nishida was not well-known then as the second edition of the Inquiry had not yet been published. In Nishitani’s words: “In any case, his name was not widely known, and certainly I had never heard of him. I bought his book only because it was the kind of title that appealed to a high school student.” He was especially impressed by the essays in the last part of the book. “Not only did I feel a greater affinity to these than to anything I had read previously, but I also felt the presence of something qualitatively different “(Nishitani, 3-4). Ironically, Thought and Experience is one of the works Nishida felt most dissatisfied with!

This, however, was not a happy period in Nishitani’s life, as he frequently refers to a “deep sense of despair,” something that is absent from Nishida’s diaries, even though Nishida’s life was plagued by a succession of personal tragedies and the echoes of a near permanent state of war. Somehow, for Nishida, these were facts of life to be overcome in the pursuit of an inquiry which was to be of benefit to the world. For Nishida there was a sense of purpose and hope. But even as a young man, Nishitani felt himself surrounded by meaninglessness. “For me it was a time laden with extreme difficulties because of a variety of external events. A sense of despair had settled inside me from which I was unable to shake free. It made everything look empty and vain; it felt like an endless desolate wind blowing through my inner parts.” (5).

Heisig writes that, upon graduation from high school, and having renounced his original plan to study law, Nishitani saw himself faced with three possible life paths: he could become a Zen monk, join a utopian community called “New Town,” or study philosophy. He chose the latter, and enrolled at the University of Kyoto, where he studied under Nishida and Tanabe (Heisig,183).

Years later, recalling this period of his life, Nishitani writes: “My life as a young man can be described in a single phrase: it was a period absolutely without hope … My life a the time lay entirely in the grips of nihility and despair … My decision, then, to study philosophy was in fact – melodramatic as it might sound – a matter of life and death … In the little history of my soul, this decision meant a kind of conversion.” (The Days of my Youth, in Heart in the Wind, a Japanese text translated and quoted by Jan Van Bragt in his Translator’s Introduction to Religion and Nothingness, xxxv)

A successful career in philosophy and a renewed interest in Zen

Nishitani graduated from Kyoto University in 1924 with a thesis titled “Das Ideale and das Reale bei Schelling und Bergson.” After a few years teaching in local high schools, he obtained an adjunct lectureship at Otani University (a Buddhist Pure Land university) in 1928, and a lectureship at Kyoto University in 1932. He kept an interest in Schelling and translated two of his books into Japanese, but his interest soon returned to mysticism, and the year 1932 also saw the publication of his History of Mysticism, which, Heisig says, “established his reputation in academic circles” (184).

Nishitani’s interest in Zen also returned, and in 1936 he took up a practice at the Rinzai Zen Shokokuji Temple in Kyoto under Master Yamazaki. Heisig notes that Nishitani had two children by then and had to practice at a place close to his home. “It was then, for the first time, that he says he understood what Nishida meant by ‘direct experience’.” “Zen became a permanent feature of his life … it was a matter, as he liked to say, … of ‘thinking and then sitting, sitting and then thinking’” (184).

In 1937, Nishitani received a scholarship from the Ministry of Education, which he had originally planned to use to study with Henri Bergson in Paris. This, however, turned out to be impossible due to Bergson’s ill health, and Nishitani chose to instead go to Freiburg where he spent two years studying with Heidegger, who was lecturing on Nietzsche at the time. While there, Nishitani was allowed to give a talk on Thus Spoke Zarathustra and on Meister Eckhart.

Misunderstood foreys into politics

In 1943, Nishitani was appointed “chair” of the department of religion at Kyoto University, and two years later, with the help of Nishida, was awarded an (habilitation) doctorate with a thesis titled “Prolegomenon to a Philosophy of Religion.”

Already in 1941, however, Nishitani had ventured into the publication of a politically engaged work – View of the World, View of the Nation – which was widely read. In keeping with the notion that the really real is the phenomenal, and therefore the historical, as Nishida had also stated, Nishitani saw it as his responsibility to help the Japanese intellectuals become aware of the urgent need to develop a healthy understanding and practice of nationhood. Only a century before, Japan had been a feudal society secluded from the rest of the world, and when that seclusion had ended, it had fallen into the trap of militarism, with fifty years of a nearly permanent state of war. The country had obviously not learned how to be a democracy … History shows again and again that no country can go from a rule by feudal war lords to a democratic constitutional regime in just one leap. The book was meant to lay the foundations on which a healthy sense of nationhood could be built from the same standpoint of emptiness as had been established for individuals. The same wish to enlighten the political and military elite prompted Nishitani to take part in the Chuokoren Discussions, which had been set up by senior figures in the Navy to moderate the ultra-nationalism of the generals at the head of the Army. But, of course, in a climate where propaganda, rather than cool thinking, rules, it was easy to interpret encouraging a sense of nationhood as an expression of nationalism pure and simple.

As a result, during the war, Nishitani came under suspicion because of the internationalist framework in which his concept of nationhood was worked out – the Chuokoren Journal was censored and eventually shut down in 1944 for being too liberal, and Nishitani himself was placed under the surveillance of the Special Higher Police. But, once the war was over, along with a number of other academics, he was accused of having supported the wartime government, and banned from teaching by the American occupation authorities. Heisig deals with the question in some depth in Philosophers of Nothingness.

Academic exile and the publication of Religion and Nothingness

Nishitani was in fact barred from holding any public office. So he spent the five years until his reinstatement in 1952 once again facing nihilism, perhaps now better equiped thanks to a renewed sitting practice, the support of his wife, and writing. Heisig notes that these years saw the publication of A Study of Aristotle, God and Absolute Nothingness, and Nihilism (to be translated as The Self-Overcoming of Nihilism in 1990), all of which Tanabe Hajime hailed as “masterpieces.” Heisig remarks that though “the stigma the Occupation forces intended did not have the crippling effect one might imagine … Nishitani took it as an opportunity to rethink his philosophical vocation … preferring to think about the insight of the individual rather than the reform of the social order” (183-184).

It is, however, only after he was reinstated in his post at Kyoto University that Nishitani wrote the essays later published under the Japanese title Shūkyō to wa nanika, meaning “What is Religion?,” a title it retained in its German translation “Was ist Religion?” but was changed to Religion and Nothingness for the English translation by Jan Van Bragt.

A unique philosophical style

Though Nishida is usually regarded as philosophically the most creative – which has resulted in his being the thinker of choice as the subject of doctoral dissertations – it is Nishitani’s more elegant style that has drawn most readers to the Kyoto School. Heisig writes that “Nishitani’s mature style, as it has come to the west in translation, shows a buoyancy of expression, a liberal use of the Zen tradition, and a gift for concrete examples that make it stylistically Nishida’s and Tanabe’s superior. Without Nishitani’s genuine feel for the heart of the philosophical problems that Nishida and Tanabe were dealing with, and for their relationship with the fundamental problems of the age, I have no hesitation in saying that the term “Kyoto School” would have little of the currency it now enjoys” (187).

One can detect in Nishitani’s style a distinct Heideggerian influence, but repetition is also a feature of Eastern preference for a “wholistic” embrace of the totality, followed by a sort of circumnavigation of the issue, from all angles, which is not just a circular exploration, but moves like a spiral, going deeper each time a circle has been completed. This approach will most likely throw readers used to dialectical arguments out of their comfort zone. In fact, it is exactly what it is meant to do, as they need to break with objective, calculative thinking from the standpoint of being, and allow themselves to embrace reality intuitively from the standpoint of emptiness. You are, as it were, taught to swim in this new element through the practice of following the writer on his spiral journey. Nishitani’s point is not to build a system, but to teach the reader to feel at home and think from the standpoint of emptiness.

Still teaching throughout retirement

Nishitani retired from Kyoto University in 1963, but he then went back to Otani University as Professor of philosophy and religion. He also became president of the Eastern Buddhist Society, taught at the University of Hamburg as a visiting professor, and served as chief editor of The Eastern Buddhist. Heisig also notes that, as he was living in Kyoto, he was frequently invited to give public lectures and take part in debates and roundtables both in Japan and abroad. A Symposium on Religion and Nothingness was held at Smith and Amherst Colleges in April 1984, which Nishitani was unfortunately unable to attend as his wife was in hospital. He instead sent a paper “Encounter with Emptiness” (containing the text cited at the top of this page). Papers presented by the scholars who spoke at this Symposium have been published in The Religious Philosophy of Nishitani Keiji, edited by Taitetsu Unno, in 1989.

Nishitani died in Kyoto in November 1990. Nishitani’s death triggered a surge of interest, not only in his works, but also in those of other philosophers of the Kyoto School, which resulted in a spate of translations and publications of their works during the following years.

Sources:

Nishitani Keiji, “Encounter with Emptiness,” in Taitetsu Unno, The Religious Philosophy of Nishitani Keiji (1989)

Nishitani Keiji – Nishida Kitaro (1991)

James Heisig – Philosophers of Nothingness (2001)

Nishitani Keiji – Religion and Nothingness (1982)