“Concretely, the acting-seeing body is a way that the world knows itself and lets things be seen. In Nishida, we could say, the site of agency shifts from the body – considered as relatively self-contained – to the world itself, with the proviso that the acting-seeing body then counts as a site through which this world acts and lets things be seen” (John Maraldo).

Pure experience and intellectual intuition

Nishida’s maiden work An Inquiry into the Good opens with the words: “To experience means to know facts just as they are, to know in accordance with facts by completely relinquishing one’s own fabrications … by pure I am referring to the state of experience just as it is without the least addition of deliberative discrimination” (Inquiry, 3).

Nishida’s name is still for many closely associated with this notion of “pure experience,” a phrase he borrowed from the American philosopher and psychologist William James. Nishida further defines “pure experience” as follows: “The moment of seeing a color or hearing a sound … is prior not only the thought that the color or sound is the activity of an external object or that one is sensing it, but although to the judgment of what the color or sound might be like … pure experience is identical with direct experience. When one directly experiences one’s own state of consciousness, there is not yet a subject or an object, and knowing and its object are completely unified. This is the most refined type of experience” (Inquiry, 3-4).

In Chapter 2, Nishida writes: “Pure experience includes thinking” (Inquiry, 17). “Thinking and intuition are usually considered to be totally different activities, but when we view them as facts of consciousness we realise that they are the same kind of activity” (Inquiry, 41). This leads Nishida to introduce the concept of “intellectual intuition” in chapter 4, which he explains as follows: “Ordinary perception is never purely simple, for it contains ideal elements and is compositional. Though I am presently looking at something … I see it as mediated in an explanatory manner through the force of past experience.” He even says that “Intellectual intuition is an intuition of ideal, usually trans-experiential things. It intuits that which can be know dialectically. Examples of this are found in the intuition of artists and people of religion. With respect to the process of intuiting, intellectual intuition is identical to ordinary perception, but with respect to content, intellectual intuition is far richer and more profound” (Inquiry, 30). Still, Nishida is keen to add that intellectual intuition is not “a kind of mystical ability.” He also says that “though there are things that I cannot intuit now, this does not mean that nobody can. It is said that when Mozart composed music, including his long pieces, he could discern the whole at once, like a picture or a statue.” Further down, Nishida writes: “A true intellectual intuition is the unifying activity in pure experience. It is a grasp of life, like having the knack of an art or, more profoundly, the aesthetic spirit” (Inquiry, 32). And again, he insists that “it is an extremely ordinary phenomenon … from the standpoint of pure experience it is actually the state of oneness of subject and object, a fusion of knowing and willing” (Inquiry, 32). Although he may not have had as clear a grasp of it as he wished, at this point in his life, it is worth noting that the association of the words “intuition” and “activity” was at the centre of Nishida’s inquiry from the start. It is from there that Nishida’s thought evolved toward the use of the term “action-intuition” which John Maraldo explores in the chapter he dedicates to “Enaction in Cognitive Science and Nishida’s Turn of Intuition into Action” in his book Japanese Philosophy in the Making 1.

Nishida’s concept of “action-intuition” (koi-teki chokkon)

While Nishida’s publication of Inquiry into the Good in 1911 attracted a lot of attention, in addition to an invitation to teach at Kyoto University, a second publication in 1921 was a bestseller for a book on philosophy. But it is in the third publication of the book in 1936 that one finds the following, which Nishida includes in a second preface:

“The second half of my book From What Acts to What Sees turns the standpoint of pure experience around until it arrives at the notion of ‘place’ … The notion of ‘place’ was rendered concrete in ‘the dialectical universal’, and its standpoint was made immediate as the standpoint of koi-teki chokkan; its world, the very world of poiesis, is itself the world of pure experience came to be thought of as the world of historical reality.”

Maraldo comments: “This often quoted statement from a preface to Nishida’s first book introduces the notion of koi-teki chokkan as a transformation of pure experience that would avoid its psychologistic connotations but retain its sense of immediate contact prior to a subject-object split. The statement points to another kind of knowing, not conceptual knowing but rather something akin to practical knowing. It implies that experience (and the experiencing self) are not separable from practice or action, and so places them in the context of the world in which they occur, ‘the world of historical reality’.” In other words, “when the reader of Nishida probes for what it is that acts and that sees – for an agent behind the action and the intuition – koi-teki chokkan seems mysteriously to intimate that the world itself comes to create and to ‘see’ itself through human actions. At first sight this notion seems to shift agency to what ordinarily counts as the realm of objects seen or acted upon, or at best to an objective set of conditions influencing a seeing and acting organism.” Maraldo then notes that “as Nishida qualifies the sense of agency … it bears a striking resemblance to recent theories in cognitive science. The notion of enaction in cognitive science also shifts the sense of agency: agency resides not in an individual ‘mind’ or consciousness responding to input from the outside world, but rather in an interacting complex that embraces both the body that acts in the world and the world that is brought about and re-constitutes the acting body. New theories of agency help make sense of Nishida, clarify some ambiguities in his philosophy, and in turn are subject to criticism from his standpoint.”

Before delving into a comparison with modern cognitive science, Maraldo needs to explain how two concepts such as action (koi) and intuition (chokkan), that are traditionally held to be diametrically opposed, came to be paired in “action-intuition.”

Why intuition?

In an essay dated 1937, Nishida wrote: “Action-oriented intuition – to give a preliminary translation of Nishida’s term – first of all reverses traditional notions of intuition. What I mean by this term is the reverse of something like Plotinus’ intuition or Bergson’s pure duration.” “In other words,” Maraldo comments, “it is the reverse of an intuition that serves as the means by which pure intellect directly sees truth – the means to ‘illumination’ in Plotinus’ philosophy. It is also the reverse of Bergson’s intuition of duration that proceeds by directly entering into oneself and things from within, and that serves as a means to absolute knowledge. More generally, Nishida contrasts his term with all notions of intuition that imply a form of knowledge that bypasses bodily action.” Nishida adds: “When one speaks of intuition, one usually thinks simply of an immersion of the self into things, where action ceases. But we must regard this point of departure as problematic. The activity of cognition also necessarily occurs or functions within the historical world.”

Maraldo points out that, while intuition retains “its traditional link to cognition” … for Nishida “cognition [is] placed not in the mind but in ‘the historical world’, the world of concrete, everyday human interactions. The beginning of his essay makes it clear that, for Nishida, intuition is a form of knowledge that occurs in an interactive world that forms or constitutes the knower. Nishida rejects the presupposition that the knower is initially a passive recipient pre-existing the known world.” This is the insight that had been absent from Inquiry into the Good, and that Nishida brought to us with the term koi-tekki chokkon. This is, I believe, what has been termed Nishida’s Copernican Revolution, whereby he turned away from the focus on “man” as the subject that enacts intuition to a concept of intuition which, as it were, originates in the world, and which we receive “relationally” as we interact with the world. Maraldo says that “the closer analogue [in Western philosophy] is that between Husserl’s categorical intuition and Nishida’s later notion of action-oriented intuition. While both describe a straightforward apprehension of relationships and states of affairs, Nishida’s notion will shift the emphasis from subjective consciousness to bodily actions that actualize relationships and states of affairs.”

Maraldo concludes his investigation of Nishida’s view of intuition with the following: “What these various notions in early Nishida and in the other philosophers have in common is a basic sense of intuition as direct, non-discursive apprehension, a kind of cognition that does not require step-by-step analytic thinking and judgment. For all its differences with traditional notions, Nishida’s later notion of action-oriented intuition retains this basic sense of intuition as a unitary, if not momentary apprehension of things. Nishida continues to invoke the term intuition to indicate that action can function as a form of knowing. If much contemporary philosophy finds the term ‘intuition’ problematic and cognitive science tends to eschew the term altogether, what we may retain in Nishida’s notion is the insight that human actions are not merely the result of cognitive mental activity; they inform cognition and are formative of it.”

Why “action”?

Maraldo writes: “Action (koi) commonly names an activity that originates in an individual body and is directed outwardly, toward other individuals or things in the world, or towards some part of the same body. Actions in this general sense originate either unconsciously from an individual’s mind, or deliberately from a subject’s will.” He notes, however, that in the West, “raising my arm or waving goodbye count as actions whether spontaneous or deliberate” whereas “the way the body heals a wound or circulate blood,” don’t. “Nishida retains the sense of an activity that engages the individual body as a whole. Yet his usage of the term displaces the origin of action in the individual body and places it rather in the interaction between individuals and their life-environment – the ‘historical world’ in his terms.”

So, along with a shift in Nishida’s view of “intuition,” one finds that his notion of the body similarly undergoes a shift. “Body ordinarily names an autonomous physical entity that can retain its identity in relative isolation from its environment, and can define itself as selfsame even if changing throughout its lifetime … In contrast, Nishida places the identity of one’s body in a history that includes one’s cultural and social heritage as well as one’s personal, biological history.” I can’t help seeing here an echo of Watsuji Tetsuro’s concept of fudo. “The body is fundamentally historical; its existence and its identity emerge from its interactions with a world that is likewise fundamentally historical … Nishida envisions the embodied self as a historical, practical body, through which the world manifests or expresses itself. The body then is not the sole doer or agent, the subject of an action, but one side of an interplay (a dialectical relationship) with the world that continually forms in response to it and reciprocally forms it. Agency is placed in this interplay, rather than in a relatively autonomous and separable entity called the body.” Maraldo also notes that Nishida does not reduce the body to “a non-conscious, purely physiological entity in the world that ‘acts’ primarily without knowing it is acting” saying that “this point will be crucial in establishing his difference from many stances in the cognitive sciences. Nishida writes, on the contrary, that we may speak of a ‘formative subject’ in the sense that ‘the body is what sees as well as what acts’.” Yet he also avoids reducing agency to mental acts: what sees and acts is the historical body acting in the world … More concretely, the acting-seeing body is a way that the world knows itself and ‘lets things be seen’. In Nishida, we could say, the site of agency shifts from the body – considered as relatively self-contained – to the world itself, with the proviso that the acting-seeing body then counts as a site through which this world acts and lets things be seen.”

“Koi-teki chokkan” in artistic creation

Artistic creation is most probably what Nishida had in mind when he was working out his inquiry into the pairing of action and intuition. Artistic creation is commonly seen as the activity of an artist in whose mind the creative impulse arises, and who then, through bodily actions, produces an aesthetic artifact. In this view, the work of art is the creation of human subjectivity. “In contrast to this commonplace view,” Maraldo writes, “Nishida envisions the artist not as an entity who simply preexists the creation of the artwork, but as someone who intuits the world by transforming it – a process that creates not only a work but the artist and a newly emergent world as well. Artist and work form mutually and are reflected in one another … in Nishida’s explanation, there is a place or basho wherein intuiting entails acting and acting entails intuiting. The artist comes to know a world partially of her own making, and comes to know herself as progressively made by that world.” This is what is meant by the sentence “letting things be and be seen.”

Two crucial qualifications

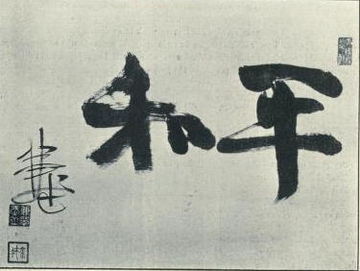

Maraldo here attracts our attention to “two crucial qualifications suggested by Nishida’s explanation.” He explains: “First for world to let things be seen, the self imposing its will must withdraw.” A note indicates that Nishida in his last essay provides a quote from Dogen to clarify what he means by koi-teki chokkon: “If you think you are realizing the world of phenomena by advancing yourself into them, that is delusion. Letting the world of phenomena come to you, that is realization.” Then he adds: “truly egoless action must be performative-intuitive.” In other words, “Whatever role the artist’s intention and willful action play, at some point in the execution of the work, the artist gives herself over to the process of creation and becomes a participant in the process of creation. If the artist at work attempts to control all factors in the making of the art, she will merely impede its creation and therefore herself precisely as an artist.” In the words of calligrapher Morita Shiryu: “Only in the moment I and the brush truly become one, does it really happen that ‘I do calligraphy’ … I and the brush are one … I am not something restricted by the brush. In a sense, then, it is not that the self performs the actions that result in an objective work, but that the actions within performative intuition actually perform the freely acting self.”

“The second qualification implied in Nishida’s explanation is that the relevant actions are practiced actions. Nishida calls koi-teki chokkan a kind of practice or discipline. In the case of artistic creation, the aspiring artist must master materials and techniques until her performance becomes second nature. The actions develop as a repeated interplay between a set of contingent worldly conditions and a performative self that respond to each other.” This is what, in the end, will differentiate Nishida’s “action-intuition” from Francisco Varela’s concept of enaction, which he is prepared to apply to “propositional” statements, that is, purely abstract assertions with no link to concrete experience.

“Koi-teki chokkan” in the practice of science

Maraldo writes: “Scientific knowledge is commonly regarded as the verification of hypotheses by repeatable experimentation performed by detached, objective observers. The ideal detachment of the observer requires her disengagement with the conditions under investigation as well as her disinterest in the results of the experiments. She herself, it is thought, must stand outside the set of conditions she is testing and must be willing equally to have the hypothesis falsified or verified.” Some scholars, in particular Jürgen Habermas and post-modern philosophers, as well as Thomas Kuhn, have argued that complete “disengagement” is impossible, as scientists are always shaped by specific paradigms.

Maraldo sums up Nishida’s ideas on this question as laid out in his last essay:

“… We may understand that … performative intuition not only as placing the scientist within the world, but also as implying that the world is re-created through scientific activity. Rather than simply being there independent of our understanding and actions, the world is transformed through them and reciprocally re-creates us. The interplay of technology, theoretical science, and everyday life provides an example. Technology is not simply the application of scientific research, and scientific knowledge is not the sole genesis of technology … Computers are an obvious example. Behind both the generation and the application of scientific knowledge lie both insight gained directly through action and action that embodies direct insight.” Maraldo concludes, however: “The precise link between concrete, performative intuition and abstract scientific thinking, however, remains unclarified in Nishida.”

Maraldo states that “a third paradigm, even less elaborated by Nishida, is social praxis: The claim that performative intuition is a way in which the historical world ‘determines itself’ implies a more limited claim: in the form of trans-individual practices, performative intuition functions as the agent in creating the world of human cultures and societies … Tanabe criticized Nishida’s notion of koi-teki chokkon as either a contemplative stance or a naturalist position appealing to instinct that cannot account for social praxis.”

The 1930’s and, even more so, the war years in the 1940’s were marked in Japan by a spiraling control of politics by nationalists, and it would have been difficult for Nishida to express his own ideas on the matter. But since Tanabe explicitly supported the nationalist movement, he obviously had no qualms with talking about it publicly.

Sources:

Nishida Kitaro – An Inquiry into the Good (1911)

John C Maraldo – Japanese Philosophy in the Making 1 – Crossing Paths with Nishida (2017)