“In the position I am articulating, the self is to be understood as existing in [the] dynamic dimension wherein each existential act of consciousness, as a self-expressive determination of the world, simultaneously reflects the world’s self-expression within itself and forms itself through its own self-expression. “

Nishida Kitaro, “The Logic of the Place of Nothingness and the Religious Worldview” (Last Writings)

The self: a Buddhist taboo

The one tennet Buddhism is readily associated with, second only to its non-belief in a god, is its assertion that the self has no substantial inherent being. The Buddha used the word anatman to refer to this non-existence, which is simply the opposite of atman, the word used in the Upanisads to refer to the individual self, believed to share the same essential nature as Brahman, the Cosmic Self. As such, atman participated in the ultimate nature of Being. Denying the existence of the individual self went hand in hand with refuting the description of ultimate reality as a higher mode of “being.” For this reason, anatman is often translated as “nonself,” meaning that what, in ordinary life, we call the self is nothing but illusion. This has resulted in the word “self” becoming taboo in Buddhist teachings for many centuries, especially in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism. When Buddhism entered China, however, the taboo was relaxed, as ultimate reality there was apprehended as the Dao, the empty but dynamic source of life and all things, rather than a substantial higher being as had been the case in Brahmanical India. Dogen did not hesitate to use the word “self” when he stated that “to study the self is to forget the self.”

Pure experience

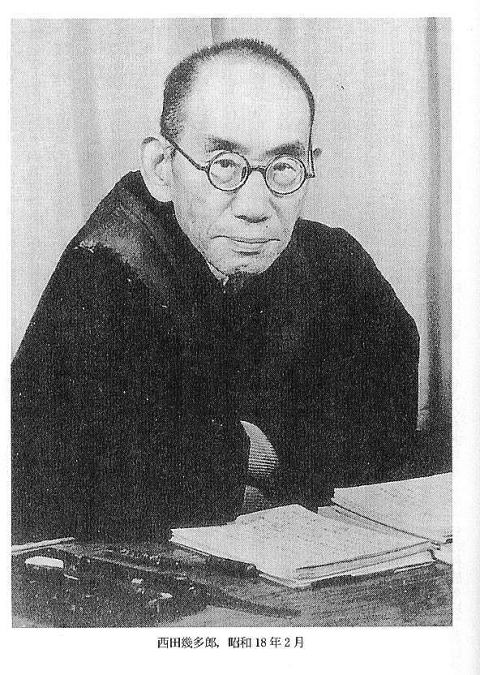

Just as Dogen (1200-1253) is now regarded as the most significant philosopher in ancient Japan, Nishida Kitaro (1870-1945), the founder of the Kyoto School of Philosophy, is seen today as the most influential philosopher in modern Japan. Born at the beginning of the Meiji era marking the opening of Japan to the West, Nishida received a broad education spanning Western and East Asian cultures, with early studies in Chinese Classics, Western mathematics and science, a degree from Tokyo Imperial University in Western philosophy, as well as a meditation and koan practice with Rinzai Zen teachers. Nishida’s original ambition as a philosopher was to reformulate the traditional East Asian worldview, as encapsulated in Zen, in the language of Western philosophy. What Nishida actually achieved has been a deepening of philosophy itself, as he returned to its foundations, and re-examined them from the standpoint of “pure experience,” akin to the Zen state of no-mind, which he believed to be “the most immediate and most fundamental standpoint” (“My Philosophical Path” quoted by Michiko Yusa).

With Inquiry into the Good (1911, translated into English in 1990), Nishida entered the philosophical conversation with the new doors that had just been opened by empiricism and phenomenology – a return to experience, to the things themselves – and started with an elucidation of what he meant by “pure experience.” “To experience means to know facts just as they are, to know in accordance with facts by completely relinquishing one’s own fabrications … by pure I am referring to the state of experience just as it is without the least addition of deliberative discrimination.”

Nishida had borrowed the term from William James’s The Varieties of Religious Experience, but he was, from the start, critical of James’ exclusive focus on the damage done by the concepts carved out of the “aboriginal sensible muchness” of non-differentiated reality, because such a focus belongs to the standpoint of the subject positing itself as separate from the object, looking at what it judges to be an impoverished world outside itself, and this was precisely the standpoint Nishida was seeking to stay clear of. He instead wanted to remain in the state of consciousness where subject and object are unified. “Pure experience is identical with direct experience. When one directly experiences one’s own state of consciousness, there is not yet a subject and an object, and knowing and its object are completely unified. This is the most refined type of experience.”

The self as a unifying act of consciousness

So, whereas James focused on the carvings as damage done to the aboriginal flow which perhaps should be reversed, Nishida pointed out that there could be really no such thing as a world outside consciousness, since “to intuit things in themselves apart from our consciousness is impossible.” So, what we see as reality is made up of phenomena of our consciousness. “The so-called objective world … consists of these phenomena unified by a kind of unifying activity.” This unifying activity is intuition itself. That is, the very insight through which I grasp reality is at the same time the unifying activity which organises reality into a world. It is not a grasp by a discursive mind cutting up abstract concepts out of undifferentiated perception in order to make sense of a world outside ourselves. Intuition is a wholistic embrace by the heart-mind (Chinese xin, Japanese kokoro), it is a grasp by one’s whole self, from moment to moment, in the midst of life.

Nishida, in keeping with the East Asian Daoist dynamic apprehension of reality, thus redefined the self as an activity, the unifying activity of consciousness, which operates through intuition involving both the mind and the heart. And, in his view, “all of our knowledge must be constructed upon such intuitive experience.”

Intellectual intuition: ordinary perception is compositional

Intuition has a bad name in the West. For many it means little more than having a “gut feeling” about something. There was therefore a need for Nishida to flesh out what he meant by intuition, especially when he said that intuition is the “unifying activity of consciousness.” At the same time as he read William James’s writings, Nishida identified Henri Bergson as possibly the only philosopher in the West to have elected to use intuition as a starting point for his philosophical investigation, instead of relying on discursive thought.

When Nishida introduced the term “intellectual intuition” in the last chapter of Part I of the Inquiry, he explained that “ordinary perception is never purely simple, for it contains ideal elements and is compositional. Though I am presently looking at something … I see it as mediated in an explanatory manner through the force of past experience.” From moment to moment, as I go through life, I have an intuitive, wholistic, interpretative, grasp of my situation in the world on the basis of which I can make decisions. Nishida’s “intellectual intuition” is not a form of “sense perception,” but a grasping of “ideal” objects, such as the “unity” that underlies all awareness.

In the restored continuity of reality as phenomena of consciousness “Pure experience includes thinking … Thinking and intuition are usually considered to be totally different activities, but when we view them as facts of consciousness we realise that they are the same kind of activity.” Hence the addition of “intellectual” to intuition. In later works, Nishida referred to this intellectual intuition as an “acting-intuiting.”

Where James had seen a carving of concepts impoverishing our experience of reality, Nishida saw the unifying activity of our consciousness organising the world into a set of meaningful relationships. Earlier in the history of Buddhism, such a set of relationships had been called by the Huayan school the “mutual identity and interpenetration of all phenomena.” Our self, then, is what each act of “our” consciousness does. It is not a substance, but an activity, ultimately that of life itself, flowing through us as well as through all other things in the universe and, in our case, bringing into our reflective consciousness the forms of the phenomena we see in the world. Later in his life, Nishida spoke of the conscious self as the “place” where the formless (empty) reality determines itself into the forms of the phenomenal world. Note that, even though Zen meditation was instrumental in allowing Nishida to arrive at this insight, this self-determination carried out by the heart-mind, and mediated by intellectual intuition, is taking place within us as an everyday occurrence, whether we practice Buddhism or not, as it is “our most natural, unified state of consciousness.” Buddhism only provides the non-egocentric standpoint which allows us to open up to the process instead of blocking it by trying to impose the reified concepts of received views on what we perceive, because we’d rather stick to the safety of a solid order than engage in the challenge of having to re-adjust our views to take into account constantly emerging new facts.

“I and the world”

Nishida’s most productive years, both in terms of the evolution of his thought and his scholarly output, were those that followed his retirement from Kyoto University in 1928. The many essays Nishida wrote in those years were collected into six volumes of Philosophical Essays, now accessible in Japanese in his Collected Works, but for the most part not translated into English or any other Western language. An overview of Nishida’s mature thought is, however, available to non-Japanese speakers in his last essay – The Logic of the Place of Nothingness and the Religious Worldview, completed just days before his death in June 1945, and included in Last Writings (1987). For those interested, a detailed account of Nishida’s philosophical journey can be found in Michiko Yusa’s outstanding Zen and Philosophy: An Intellectual Biography of Nishida Kitaro (2002). Yusa was able to delve into Nishida’s successive diaries, and pinpoint each stage of his philosophical inquiry within the wider context of his eventful life.

Yusa notes for the year 1929 in his diary the writing of essays with titles such as “The self-determination of the universal and self-consciousness,” and “The determination of the universal viewed from the perspective of the determination of self-consciousness.” Then in 1933, Yusa notes that in “I and the world,” Nishida shifted “his focus of investigation from the self-conscious self to the “world.”

“That I am consciously active means that I determine myself by expressing the world in myself.”

Apart from Yusa’s biography, Last Writings is the most accessible source on Nishida’s later thinking for non-Japanese speakers.

In Last Writings, Nishida describes the relationship between the self and the world as follows: “In the position I am articulating, the self is to be understood as existing in [the] dynamic dimension wherein each existential act of consciousness, as a self-expressive determination of the world, simultaneously reflects the world’s self-expression within itself and forms itself through its own self-expression.”

The self is still seen as an the activity of consciousness, but the focus is now on the world as the “source” of the activity, as it determines itself through our consciousness, and the self seen as the “place” where this activity of self-determination is occurring.

In Nishida’s words, “When I say that the consciously active individual exists in a structure of dynamic expression, I mean precisely this. That I am consciously active means that I determine myself by expressing the world in myself. I am an expressive monad of the world.”

The activity whereby the world self-expresses through our conscious/active living self, is at the same time, constitutive of our individual selves. There is no existential loss of the “self” as the self is as such the activity of self-expression of the world, not “what” (that is, the substantial object) I see as “my self.” Nor is it the case that I am “lived through” by the activity of life, as this activity has become my “subjectivity.”

From the created to the creating, from the formed to the forming

Robert E. Carter, one of the first scholars in the West to have studied Nishida’s thought, expanded on the process as described in Nishida’s Philosophical Essays: “We are determined by the world, and yet we ourselves determine the world. This important mutuality must not be lost sight of, for we are not victims, but creators. From the created to the creating (from creatus to creans), from the formed to the forming is how [Nishida] describes our situation: we are created by our inheritance and our environment, and yet, we also are capable of re-shaping our environment and of altering our inheritance both for ourselves, and for our offspring. We are shaped, and we shape; are conditioned, and yet condition; are determined by our facticity, and yet are radically free to influence and re-create our world. Our existential situation allows us a spiral-like path of change: on the one hand, we are brought back to earth again and again by our factual circumstances, and on the other, we are able to take flight into the thin air of the possible, the creative, the better, and the ideal through the freedom to imagine another set of circumstances, and to so act as to bring these into existence. We are creators of our own destiny, as well as products of our age, biology, and culture” (Encounter with Enlightenment: A Study of Japanese Ethics).

For the best part of Nishida’s life, Japan was at war, first outside its borders, then, predictably, inside as well. As Nishida was writing his last essay in Kamakura, US planes were dropping bombs all over Japan. Though not optimistic about his chances of surviving the war, Nishida was haunted with what had to be done in post-war Japan to ensure its recovery. His state of mind was not unlike our own state of mind today, as we too are caught up in an unprecedented worldwide crisis, and worry about the future.

In a context that is so close to ours, Nishida is reiterating the traditional Buddhist assertion that the self is not a substance, while at the same time, reaffirming its function as a dynamic subjectivity whereby the formless world is self-expressing and self-determinating in the here and now through each act of our consciousness. The concepts through which the world presents itself emerge through the unifying activity of consciousness. Intuition, as it embraces reality in a wholistic manner, precedes discursive thought, which is nevertheless necessary to clarify the details of our interpretation. Though Nishida’s words were meant for a primarily Japanese audience, the focus on the primacy of intuition should be especially helpful to Western readers. But the invitation to creative thinking to build a new Japan, was addressed to the Japanese people who, Nishida felt, lacked critical thinking.

In many ways, Nishida’s invitation to move “from the created to the creating” echoes Dogen’s famous verses in the Shobogenzo: “To practice and confirm all things by conveying one’s self to them, is illusion; for all things to advance forward and practice and confirm the self, is enlightenment.”

Sources:

Nishida Kitaro – An Inquiry into the Good (1911 – English 1990)

Nishida Kitaro – Last Writings (1949 – English translation 1987)

Yusa Michiko – Zen & Philosophy – An Intellectual Biography of Nishida Kitaro (2002)

Robert E. Carter – Encounter with Enlightenment: A Study of Japanese Ethics (2001)