One does not find in the West any noticeable amount of meditation being practiced outside Buddhist meditation centres, and now so-called “mindfulness” courses which sells the practice as a mere tool to people who do not really want to commit to a path of transformation that threatens their sense of self. According to Yuasa Yasuo, meditation practice has also lost much of its appeal in today’s westernised Japan. And there too, people are turning to psychotherapy, which also integrates traditional meditation techniques.

What first jumps out when comparing meditation and psychotherapy is that “Psychotherapy is a method of restoring to a normal level a neurotic patient, that is, a person who has fallen into an abnormal, pathological state. By contrast, self-cultivation through meditation is a method of training that strengthens and enhances the function of the mind to a higher level than the ordinary state, just as the practice of hygienic method and motor training heightens bodily capacities.”

To start with, however, Yuasa wishes to examine the commonalities between psychotherapy and meditation, since, after all, they are both concerned with the relationship between consciousness and the unconscious. Many Buddhist teachers in the West also work as psychotherapists. Yuasa writes: “Psychotherapy is a method for adjusting a discrepancy created between consciousness and the unconscious, whereas the purpose of self-cultivation is to strengthen the power which synthesizes the functions of consciousness and the unconscious, while learning to control the emotional patterns (the habits of the mind/heart) and complexes characteristic of oneself with the view to further transform the mind.”

How does meditation work?

Zen meditation is pretty straightforward. Yuasa writes: “The motto of Zen meditation is often called “no-thought, no-image” [munen muso]. By sitting for a long time without thinking anything at all while gazing at the tip of the nose with the eyes half-closed, one endeavors to let the welling up of wandering thoughts and delusions gradually disappear.” I feel that both Dogen and Hakuin would wish to add a bit to that, but Yuasa is more interested in the various techniques utilised by the Shingon school in the Heian period. Esoteric (otherwise known as tantric) practices have a holistic approach in their techniques, as they involve the three Mysteries (mitsu) of Body, Speech and Mind. Kukai, the Buddhist master who brought these practices to Japan, is deeply revered by the Japanese people who call him affectionately Kobo Daishi, the man who de facto brought Buddhism to ordinary people. Up to the 9th century, Buddhism had been confined to the aristocratic elite living at the Heian court.

For instance, Yuasa describes the Acalanatha sadhana where imagination plays a key part as a means of concentration, with symbols and colours addressing the heart of the cultivator, his/her emotions and feelings, that is a world away of the austere ethos of Zen sesshins, with rows of people dressed in black sitting straight staring at a bare wall while a man holding a stick walks back and forth behind them. He writes: “In the case of Acalanatha sadhana, the cultivator, thinking to oneself that one has become an Acalanatha [fudo myoo], imagines various parts of his body: the skin of Acalanatha is like the color or a red flower, one of his eyes is slanted, from his mouth fearful looking fangs stick out, his face is ornamented with jade, a wreath hangs around his neck. and he holds a sword in his right hand. Around the sword coils a white serpent. His waist is covered by a tiger hide, ornamented with jade, and his whole body shines like the sun. In this manner the cultivator uses one’s imagination in minute detail to concentrate the mind on these images.”

Yuasa then explains that “people in ancient India believed that real Buddhas and divine beings dwelt in the invisible heavenly world.” To be honest, I would rather say that ordinary (uneducated) people believe that the Buddhas dwelt in the invisible heavenly world. Shakyamuni Buddha himself, and his disciples, saw Buddhas and other divine beings as metaphors for aspects of our spiritual life, images in our minds, rather than supernatural beings endowed with omniscience and omnipotence in any way resembling the Christian God. “By worshipping these mandalas and Buddha images and reciting words of praise for them, while concentrating the mind on a Buddha-image, and by entering into a deep ecstatic state, the cultivator trains oneself to actually experience, while awake, scenes of the heavenly world where these beings dwell. Psychologically speaking, one attains a vision of the Buddhas as a kind of hallucination.” This experience is called “seeing Buddhas in meditation” [jochu ken butsu].

Yuasa explains how such practice works: “When examined from the standpoint of depth psychology, this meditation method is training to weaken the suppressive power operative on the surface of consciousness in order to activate the unconscious energy latent beneath it. In our ordinary waking state, the function of consciousness perceives an object in the external world and responds to it. However, when stimuli from the outside are shut off, the energy of the mind directed towards the outside decreases, and consequently the energy of the mind, latent beneath consciousness, become active in the course of training. This is the same psychological mechanism as having a dream. When one is asleep, the function of consciousness is arrested, and consequently the unconscious energy suppressed and concealed beneath consciousness starts to surface, and appears as images in dreams. Meditation is training to experience freely the mechanism of this state while still awake … As training deepens, the hallucinatory experiences start carrying a sense of reality, inducing in the meditator strong emotions and feelings of ecstasy.”

Yuasa notes there was a type of practice popular in his time called “autogenic training,” a relaxation technique that had been originally conceived in Germany by Heinrich Schultz in 1932. “In autogenic training,” he says, “one relaxes with the eyes closed and imagines such things as the hands getting warm or seeing a red color. Ordinarily, one or two out of ten people can see a red color through training.” Meditation, likewise, “is a method of letting surface the emotions and complexes hidden in the unconscious, and by dissolving them, one acquires free control over the unconscious energy.”

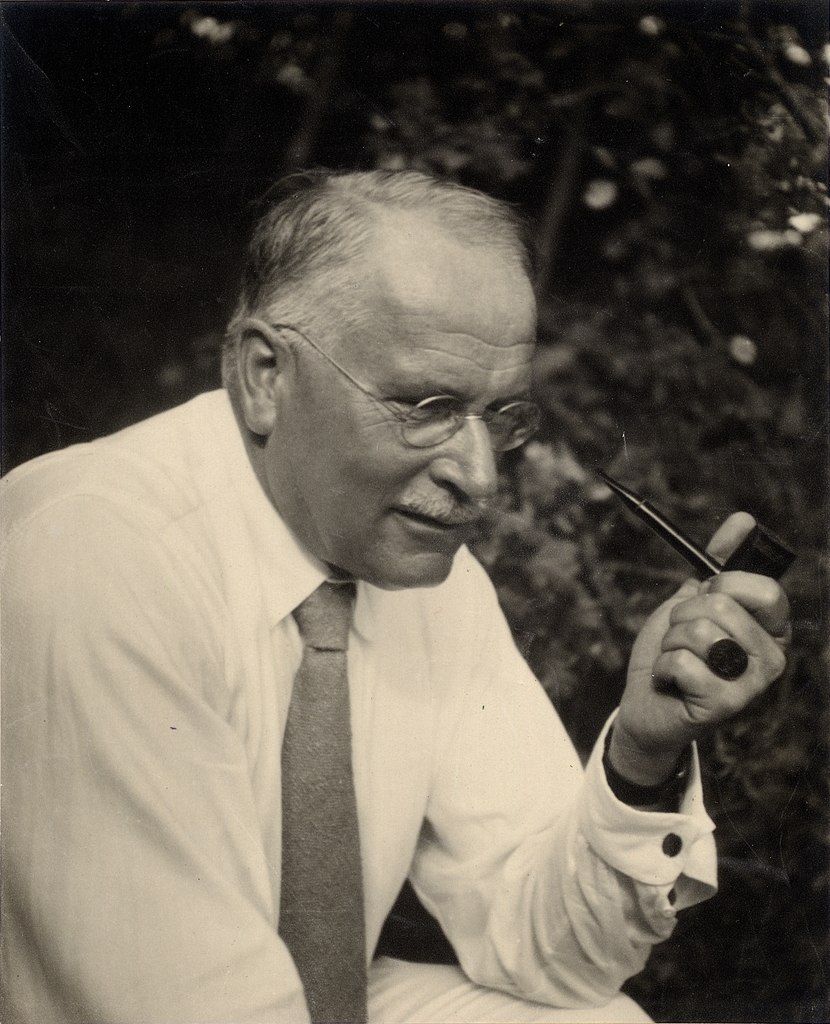

It is clear now that when Yuasa talks about the unconscious, he is not just referring to whatever we are not conscious of. His comparison between Buddhist meditation and Western psychotherapy is now leading him to engage with the unconscious as already mapped in the thought of leading psychoanalysts, especially Carl Jung. This is something I personally have not encountered in the thought of such Kyoto School thinkers as Nishida or Nishitani, or even Ueda, who was a contemporary of Yuasa. Jung was a contemporary of Nishida, Freud was five years older than him. Yuasa, on the other hand, showed a deep interest in Jung’s ideas, not only about the unconscious, but also his accounts on synchronicity, which he explores in Overcoming Modernity – Synchronicity and Image-Thinking, published after his death.

Yuasa writes: “Jung called the method of meditation which he invented himself “active imagination.” It resembles the Eastern meditation method which utilizes images as the sadhana mentioned previously. This seems to have been suggested to him by a Daoist meditation method.” He also notes that “Because Jung’s psychology spread rapidly in the US in the seventies, when gurus from India and Tibet were disseminating Eastern meditation methods, it played for Americans in bridging an understanding with the East.” And it became part of the hippie culture where psychedelic drugs were popular. “Out of this experience people developed an interest in the function of the latent energy possessed by the unconscious. An ordinary person cannot have this kind of hallucination without recourse to drugs, but through long training, persons with a certain disposition can freely experience hallucinations.”

Differences between meditation and psychotherapy

As noted above, Yuasa says: “Although they share the same psychological mechanism, the beginning points and goals differ. Psychotherapy is a method for adjusting a discrepancy created between consciousness and the unconscious, whereas the purpose of self-cultivation is to strengthen the power which synthesizes the functions of consciousness and the unconscious, while learning to control the emotional patterns (the habits of the mind/heart) and complexes characteristic of oneself with the view to further transform the mind.”

He nevertheless adds “Yet in the course of meditative training, the cultivator can run into artificial neurotic states, and it the training goes wrong, one can actually become neurotic.” Rinzai Zen practitioners familiar with the life of Hakuin know that, while he was in a solitary retreat, he suffered from a state he referred to as “Zen sickness,” that had become so serious that it prevented him from pursuing his training. Yuasa himself speaks of a monk he met who had experienced “symptoms analogous to depersonalization” or “was overtaken by anxiety while walking down the street.” Hakuin is said to have been able to cure himself through techniques of meditation combined with traditional medical and folk therapies, but nowadays “a master, like a psychoanalyst treating a patient, must clearly observe the disciple’s psychological state and guide the disciple so that he or she overcome it.”

Source:

Yuasa Yasuo – The Body, Self-Cultivation, and Ki-Energy