“Rather than a timeless and changeless transcendental realm pointing out at reality, classical Chinese functions non-mimetically. Each word is associated with the thing it names not because of a mimetic pointing at the thing from a kind of outside, but because it shares that thing’s embryonic source. Tao itself is the physical Cosmos seen as an undifferentiated source-tissue. This source-tissue is only divided into individual things when we name them. Those names emerge from the undifferentiated tissue exactly like the things they name, and they emerge at exactly the same moment (David Hinton).

Words as impediment to deep insight

David Hinton writes: “Taoist and Ch’an masters from the beginning insisted at every turn that words are the fundamental impediment to deep insight. Words, thought, ideas: they serve a practical function, an evolutionary purpose. They intend to get us somewhere: to work toward understanding, solve a problem, make a plan, all in the project of navigating the world and surviving. Ch’an is useless: it wants to go nowhere else, solve no problem.”

This is not to say, Hinton adds, that words cannot also be used to “dismantle [the] realm of words” This is the way they are used in Ch’an, especially in koans, which he calls “sangha-cases.” But first, we need “to understand how words and language functioned in ancient China – for as with mind, they functioned very differently than they do in the modern West.”

Language functions differently east and west; mimetic versus non-mimetic

Hinton explains: “In the modern West, we experience language in a mimetic sense – as a transcendental realm that looks out on the world, using words to represent it, to point at it. Language is the medium of thought, and its transcendental nature creates the illusion of mind as a transcendental identity-center. This assumes language did not evolve out of natural process. And indeed, language is described this way in the Judeo-Christian myth that still shapes Western assumptions in fundamental ways, for the language of humans was God’s language at the beginning, so it oddly predates the physical universe. When language functions in this mimetic sense, it embodies an absolute separation between the identity-center (‘soul’) and reality. And that separation defines the most fundamental level of experience.” Hinton is here referring to Plato’s doctrine whereby “being” is bestowed, as it were from above, by a metaphysical realm of edeitic forms – the Ideas – of which all the “things” we see are but copies. The Bible starts with these words: “In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters. [1:3] Then God said, ‘Let there be light’; and there was light. God saw that the light was good, and he separated the light from the darkness. God called the light ‘day’ and the darkness he called ‘dark’ and there was evening and there was morning – the first day.” And so on with water, land, vegetation, living creatures and humans.

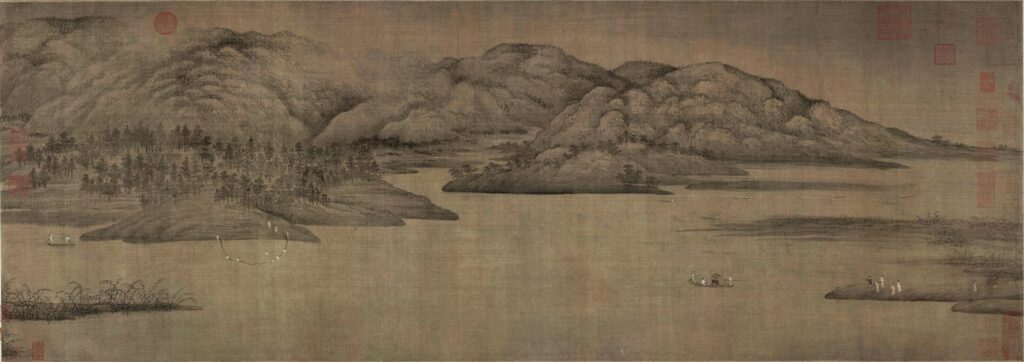

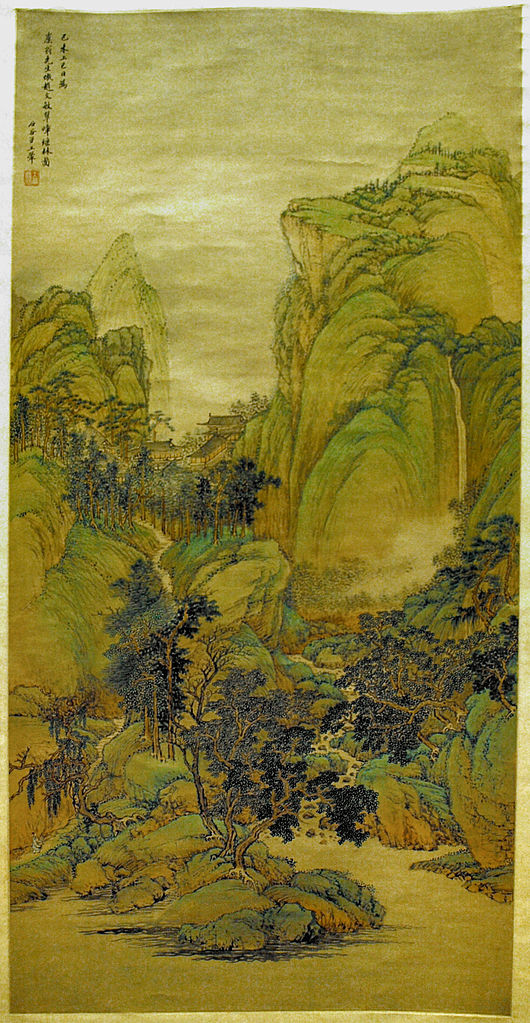

In contrast, Hinton continues, “Rather than a timeless and changeless transcendental realm pointing out at reality, classical Chinese functions non-mimetically. Each word is associated with the thing it names not because of a mimetic pointing at the thing from a kind of outside, but because it shares that thing’s embryonic source. Tao itself is the physical Cosmos seen as an undifferentiated source-tissue. This source-tissue is only divided into individual things when we name them. Those names emerge from the undifferentiated tissue exactly like the things they name, and they emerge at exactly the same moment: it is only when the word mountain appears that the mountain itself appears as an independent entity in the field of existence. The mountain exists prior to the naming, of course, but it isn’t separated out conceptually as an independent entity. And it is there at this origin-moment/place that meaning happens in classical Chinese: word and thing coming into existence together at the same moment, and therefore sharing the same root.”

Undoubtedly, behind this contrast stands “the pictographic nature of classical Chinese, wherein words are most fundamentally images of things … Pictographic Chinese words operate without the dualistic divide between empirical reality and a transcendental realm of language. In their pictographic form, they share with things their very forms. And in the cultural myth, this language emerged quite literally from the earth – for it was invented by the first human … In this, language retains its roots in the primitive, where is was oral and free of the metaphysics introduced by writing.”

“Non-mimetic language assumes the primal generative cosmology of Taoism.”

In the absence of a transcendental deity that created the world ex-nihilo, the generative activity of reality itself, under the name of Tao, had to be postulated. It may be more correct to say that such a generative activity of reality had been at the heart of the early gynocentic worldview of pre-dynastic China, so it only had to be revived. Androcentric cultures need to posit an all powerful Creator God as a “guarantor” of authority, and this turns them into patriarchal cultures. In such cultures, rule rests on power and control, and is traditionally embedded in the “sacred words” of holy scriptures, as is the case for the Christian Bible. On the other hand, “ it is only in [the] experience of reality as an all-encompassing emergent present that non-mimetic language can exist, for each word needs to operate at that very origin-moment/place, word and thing emerging into existence simultaneously. And so, we find that language too inhabits the generative origin-moment/place … Language is simply one aspect of Presence emerging from the pregnant emptiness of Absence. It has the same ontological status of the ten thousand things, and therefore belongs wholly to the cosmological process of Tao.”

“Language is an organic part of Tao’s unfolding”

So, unlike Mahayana Buddhism, where Nagarjuna described words as linked together in a conceptual layer superimposed on reality by a “cognitive fault” inherent to the mechanics of human consciousness, Taoism understood the emergence of language as a “natural pattern, one among the countless patterns that emerge as Tao unfurls into the great transformation of things. It was a manifestation of ch’i-thought/mind” – “mind as woven wholly into the ever-generative ch’i-tissue, into a living and “intelligent” Cosmos” … Even in its most carefully composed written form, language was considered an organic part of Tao’s unfolding. The word for “literary works” (and by extension culture and civilization) is an ideogram “the elemental meaning of which is “the moving patterns Tao reveals as it emerges into empirical reality”: veins in stone, ripples in water, patterns of stars and seasonal transformations. And writing was assumed to be another of those patterns … words are the ‘pattern of Tao’, especially in its most distilled form as poetry … Indeed, ‘pattern of Tao’ is the radical for a broad range of words having to do with writing, literature, and culture.”

“One can only dwell as integral to Tao prior to the differentiation and separation that naming creates”

Taoist practice, and therefore Ch’an, are the means whereby one, as it were, return to the earliest Paleolithic times, when words arose through the process of differentiation, the origin-moment/place when the ten thousand things emerged into Presence. “One can only dwell as integral to Tao prior to the differentiation and separation that naming creates, an idea that permeates Ch’an … And so, when Ch’an practice returns us to empty-mind without words and logical categories, it returns us to dwell as integral to that undifferentiated existence-tissue.” Using Buddhist terminology, Yellow-Bitterroot Mountain (Huang Po), writes: “Anything said is not dharma and is not original source-tissue mind. In this, you begin to understand dharma transmitted mind-to-mind.”

Separation between self and world in both East and West, but in the East there is no metaphysical dimension

Hinton writes: “Words are the medium of the identity-center, and with that identity-center comes a separation between self and everything else. In the West, this separation is metaphysical because of the transcendental nature of the mimetic language-realm, and because of mythologies in which the self is a ‘soul’, that transcendental spirit-center.” This, for instance, is the case in the Christian apophatic tradition, where the encounter between Moses and God in a dark cloud on Mt Sinai is used as a metaphor, Clement of Alexandria wrote: “When the Scripture says, ‘Moses entered into the thick darkness where God was’, this shows to those capable of understanding, that God is invisible and beyond expression by words.” In classical Chinese, however, “the separation exists, but there is no metaphysical dimension. Language is not a transcendental realm, and neither is the identity-center. There is a separation, the overcoming of which is the focus of Ch’an practice, but that practice is quite different because there is no metaphysical dimension involved.”

Because Tao, unlike God in Christianity, is not a transcendent entity, but instead a ‘generative source-tissue unfurling the great transformation of things’, it is possible to return to ‘the primordial place’ of the origin-moment/place when the ten thousand things emerged into Presence with the help of Ch’an meditation and sangha-case (koan). Hinton then concludes:

“But, as we will see, once it familiarizes us with that primordial place, Ch’an practice stops trying to erase language-structured thought/identity. Instead, as part of ’seeing original-nature’, it enables us to inhabit thought/identity as integral to Tao and the selfless simultaneity of its unfolding. Mind and Cosmos are a single tissue, the identity-center emerging together with language and perception and the ten thousand things at that origin-moment/place. And indeed, it is inhabiting that origin selflessly that is Ch’an’s final intent.” It is this “unity of mind and Cosmos in a single tissue” that, in Hinton’s view, constitutes the superiority of Taoist Ch’an over Buddhist Ch’an, not that it is missing in the latter, but it seems that it takes second place to the individual realisation of “awakening” and “liberation.”

Source:

David Hinton – China Root – Taoism, Ch’an, and Original Zen