“My only claim is that I have transcended Darwin, to finally free myself from the torment that the wall of Darwinism imposed on me… My theory of evolution is an evolutionism of subjectivity, or more formally, a theory of evolution presupposing subjectivity. ”

Imanishi Kinji

A pioneering primatologist and a controversial figure

Born in Kyoto in 1902, three decades after the beginning of the Meiji Era, and Japan’s opening to trade with the West under American pressure, Imanishi Kinji grew up in a country undergoing an intense process of westernisation. Though fascinated by the wealth of knowledge it had brought to the Japanese, he also found it problematic, as it was accompanied by an irresistible rise of nationalistic hubris that led Japan to engage in a series of wars against Taiwan, Russia, China, and Indochina, before becoming involved in both world wars, which resulted in its final defeat and occupation by the US in 1945.

Imanishi’s lifelong academic research was shaped by his disagreement with Darwin’s theory of evolution. He was critical of its mechanistic premises, aggravated by the key role given to random in neo-Darwinism, and the foregrounding of competition in the emergence of new species. Imanishi’s own re-interpretation emphasises the role of “subjectivity,” whereby all species at all times endeavour to “fit in” in order to “make a living” in the context of an organic network of relationships where the welfare of each individual and that of the whole species are interdependent. Accusations of anthropomorphism have been levelled at this new interpretation, and Imanishi is still regarded as a controversial figure. At the same time, however, he is widely recognised as a pioneer in primatology, where he is said to have initiated a “paradigm change” (Frans de Waal). The irony, of course, is that Imanishi’s re-interpretation of evolution rests on the same principles as those underlying his new approach in primatology!

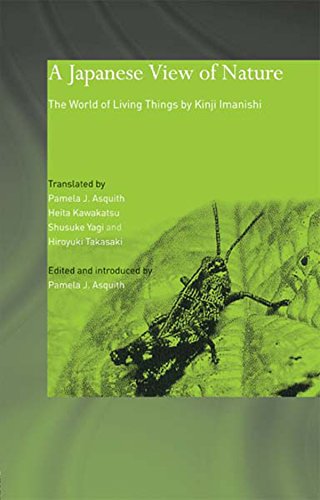

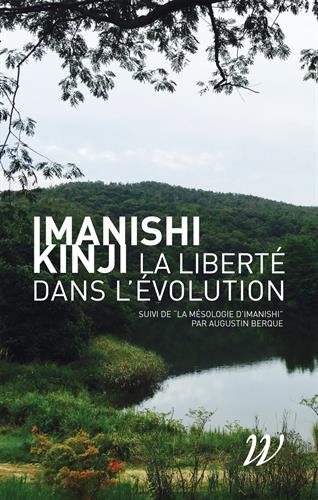

To my knowledge, only two of Imanishi’s works have been translated in a Western language. Seibutsu no Sekai was published in 1941, two years only after he received his PhD in Science from Kyoto University for his study of mayfly larvae in Japanese rivers, and just before being drafted to fight in World War II. An English edition – The World of Living Things – is the core text of a book entitled A Japanese View of Nature, published in 1945. The second book, Shutaisei no shinkaro, published in 1980, when Imanishi was 78, is one of his last works, and has been translated into French by Augustin Berque in 2002 under the title of La Liberté dans l’Evolution.

“All the things of this world result from the differentiation from one thing”

The very first lines of The World of Living Things read as follows: “Our world consists of an enormous variety of life. We may think of it as a great family of various members. It is no random gathering; each member has a role in constituting, maintaining and developing this family.” Even though, at this stage, he had only studied insect larvae, Imanishi was already thinking in terms of the bigger picture – the world, life, how they had unfolded, how life-forms related to each other. His entire career – from entomologist to primatologist, to ecologist, to anthropologist – was shaped by a deep-seated conviction that neo-Darwinism was flawed.

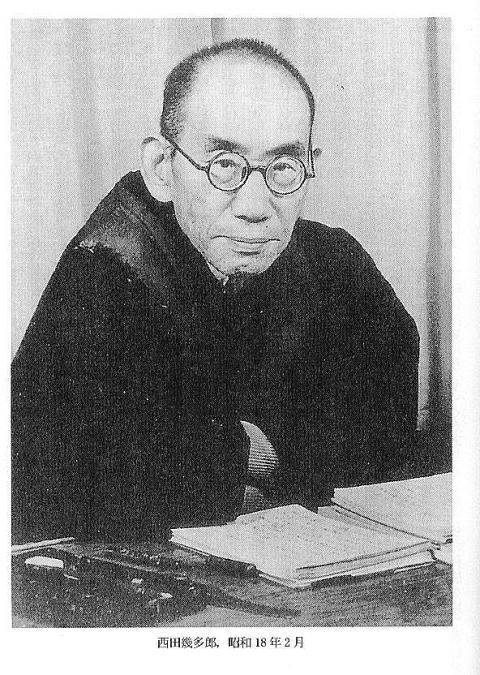

During his time at Kyoto University, Imanishi had regular contacts with Nishida Kitaro, who shared Imanishi’s disappointment with the West’s mechanistic approach to nature. Imanishi could be regarded as having spent his whole life searching for concrete evidence in the natural world for the following statement by Nishida: “The various forms, variations, and motions a plant or animal expresses are not mere unions or mechanical movements of insignificant matter, because each has an inseparable relationship to the whole, each should be regarded as a developmental expression of one unifying self … In explaining the phenomena of plants and animals, we must posit the unifying power of nature …The self of nature, that is, its unifying activity, becomes clearer as we move from inorganic crystals to organisms like plants and animals … (An Inquiry into the Good). Nishida had described the human self as the activity of consciousness, which unifies our perceptions into a meaningful whole, thereby allowing formless reality to self-determine into the phenomenal forms of the things we see (for a detailed presentation of Nishida’s thought about “the self as the world’s self-expression,” see page preceding this one). When applied to the natural world, a similar integrating process is at work in the unfolding of evolution from the one original cell into the many species we now see roaming the earth. In Imanishi’s words: “All the things of this world result from the differentiation from one thing … This single source is the basis of the fundamental relationship between everything, plants and animals, both living and non-living.” Each thing has emerged for a reason and has a function. As it has come about within the unfolding of one original cell, each new event, new behaviour, new species, necessarily “fits in” what turned into a dynamic interdependent set of relationships.

Affinity allows empathy and attunement

In the first chapter of The World –“Similarity and Difference”- Imanishi builds on this fundamental oneness to work out what should be our approach to a correct understanding of evolution. We tend to take a step back to look at things “objectively.” Imanishi, instead, is keen to get close, and seek “attunement” with the living things he observes. Because all things came from this one source, and we ourselves are part of this world, there are both similarities and differences between us and other living things. Namely, we have a higher degree of “affinity” with some species – for example, chimpanzees – than we have with others – for example, insects or amoebae. We can therefore empathise better with chimpanzees, and empathetically intuit the world as they experience it. It is a lot more difficult for us to intuit what the world of amoebae looks like!

In fact, this empathetic intuitive grasp of things has been Japan’s traditional approach to “learning.” The haiku poet Basho famously wrote: “From the pine tree, learn of the pine tree. And from the bamboo, of the bamboo.” As Nishitani Keiji, another disciple of Nishida, explains: “[Basho] calls us … to attune ourselves to the selfness of the pine tree and the selfness of the bamboo. The Japanese word for “learn” (narau) carries the sense of “taking after” something, of making an effort to stand essentially in the same mode of being as the thing one wishes to learn about” (Religion and Nothingness).

We can now get a glimpse into the way Imanishi was able to initiate a paradigm shift in the practice of primatology. Laboratories had to be left behind. Animals had to be met in their own environment, and up close, mixing with them whenever possible, to fully comprehend the motives underlying their behaviours. Imanishi carried out his study at the same period and in the same areas in Africa as Jane Goodall, who has given us superb footage of her interactions with chimpanzees.

“Structure is nothing but for function and vice versa”

In the second chapter “On Structure,” Imanishi goes on to describe how species emerged. In neo-Darwinism, a genetic mutation that gave the animal an advantage in the competition for survival would be selected as a permanent trait, while one hampering the animal would lead to its extinction. This theory reflects Descartes’s view of animals as machines unable to think or even feel. Instead, Imanishi holds that each new trait emerges in the context of a drive to become part of a dynamic network of interdependent relationships – what the Huayan doctrine of Indra’s Net called the “mutual interpenetration of all phenomena.” “Fitting in” implies that it has a function in the organic whole, and this function determines its structure and morphology. In Imanishi’s words: “Structure is nothing but for function and vice versa … what has developed from one thing is not only the structure of living things, but also the function.” Imanishi adds that while evolutionists tend to focus on the apparition of new species, one must not forget that, from the perspective of the animal, the most immediate requirement is to continually renew its body simply in order to continue living. Before it even comes to reproduce, it must secure food! As it does, the animal absorbs the foodstuffs it finds in its environment and, in that way, what it eats becomes its body. The nonliving things can therefore be seen as extensions of living things. This is how it can be said that nonliving things, on which living things depend for their lives, are also functions and parts of a structurally interdependent living whole.

Shutaisei – the autonomous subjective being

In chapter three – “On the environment,” Imanishi elucidates his controversial theory of shutaisei, the “autonomous subjective being.” Now, this notion of an autonomous, i.e. independent, subject is precisely what the Buddha had rejected early on with his doctrine of anatman. How could the disciple of a Zen Buddhist philosopher such as Nishida, entertain such a concept?

Imanishi’s starting point here is a rejection of animals as automata. He is happy to accept a material dimension to life, but he denies that life is simply an activity of matter. Instead he sees life as a process of integration of nonliving things by living things. Nishida had, likewise, seen consciousness as a process of integration/unification that makes sense of the “aboriginal sensible muchness” (William James) of an undifferentiated world. In animals, this process is not self-conscious as it is in humans. Yet, Imanishi notes, animals do “recognise” what is edible for them, they do recognise other members of their species, and react to events taking place in their environment. They may have little or no reflective self-consciousness, but they do have primary consciousness. Imanishi writes: “Reacting is recognizing, and recognizing is reacting.” Like us, they live in a world that is their own, in the sense that they have identified elements that are relevant to them, and organised them into a meaningful world that allows them to “make a living.” In that, Imanishi sees an activity of integration whereby their world is organised into an organic whole though, at the same time, taking its place as a function within other organic wholes. In Imanishi’s words, “What I wished to relate is that the life of living things, which is continuous action, is the assimilation of the environment and control of their world; that this is, in fact, the development of the autonomy which is inherent in living things … Thus, autonomy or subjectivity are characters of wholeness. Perhaps, if I could rephrase it, I would say that living things have a wholeness and autonomy; as a result, we can recognize something like mind in living things.” It looks like Pamela Asquith’s translation of shutaisei as “autonomous subjective being” was selected with mainstream evolutionary theorists in mind, leaving aside the Buddhist origin of Nishida’s thought, which Imanishi’s shutaisei obviously echoes. Imanishi thinks in terms of “wholeness,” and “life” rather than “being” (another deeply unbuddhist term) that is, he sees autonomy as another word for subjectivity understood as integrative activity. What Nishida described as the unifying activity of consciousness, Imanishi sees as the integrative activity of living things, whereby they create a world of their own, that is, a world in which they can sustain their lives. Augustin Berque translates shutaisei in French by subjectité, but, as this is a rarely used word, it was replaced by liberté (freedom) in his translation of Imanishi’s last book – La Liberté dans l’Evolution.

Nature abhors conflict

Chapter four “On Society” anticipates Imanishi’s later turn towards primatology, with a view to investigate in depth the neo-Darwinist theory of evolution, which, though criticised by many, still hold sway in mainstream evolutionary theory. Neo-Darwinism sees evolution strictly in terms of biological processes, thus denying animals any creative activity in the way they live. Shutaisei restores to animals the equivalent of a mind. “Although living things cannot freely create or transform their environment, neither are they entirely controlled by it. Rather, from their respective points of view, they continuously act on and try to control the environment.”

To be precise, Imanishi does recognise that there is competition for resources, and that it has played a part in the emergence of various life-forms. But this competition is taking place within a wider context of cooperation, which is that of the species. “People tend to think of reproduction or breeding as the preservation or maintenance of the species. However, from the perspective of the individual, it is ultimately the maintenance of the individual. Although an individual dies, the place it occupied in this world is maintained by creating and leaving another which is similar to itself; thus this world is maintained.” Members of a species gather because they have the same needs. However, because they have the same life requirements, they also come into competition for food resources. So there is a double process whereby animals congregate, and at the same time disperse into groups within the particular continuous environment they depend on for sustenance. Imanishi asserts that “this shared life does not necesssarily imply a conscious and active cooperation; rather, as the result of the interactive influence among individuals of the same species, a kind of continuous equilibrium results. Outside this equilibrium, an individual’s survival is no longer assured.” Even the relationship between predator and prey is at once an aggression and a mode of interdependence. “In one sense the relationship between host and parasite and that between predator and herbivore is the same, in that they cannot consume all the food with impunity … If the parasite overcomes the host, the parasitic relationship vanishes.”

Here comes into view a world based on a shared life within species in order to secure the survival of individuals. Only within that cooperative set up does competition occurs, and even when it does, it must remain within limits so that cooperation is safeguarded. When a parasite kills its host, it is putting an end to its own life.

“A theory of evolution presupposing subjectivity. ”

Whereas Imanishi’s ideas about subjectivity are best developed in the World, which he wrote before his involvement in primatology, a more detailed presentation of his critique of neo-Darwinism is available in La Liberté dans l’Evolution written when he was 78, after many years spent studying macaques in Japan, and gorillas and chimpanzees in Africa with Jun’ichiro Itani, a younger disciple of Nishida. At the same time he studied hunter-gatherers and nomadic pastoralists in Tanzania, and became professor of Social Anthropology at Kyoto University. Imanishi is regarded as the founder of Japanese primatology, and his ideas have impacted primatology worldwide.

As noted above, Imanishi does not denies the role of matter in evolution. Neither does he reject the existence of random mutation and natural selection, with competition for food resources as a contributor to survival. What he denies is that these are “the prime movers in speciation.” In his view, shutaisei, the mind-like integrative activity of living things is the prime mover.

In La Liberté dans l’Evolution, Imanishi retraces the unfolding of his research as a primatologist and anthropologist focused on the origin of the human species as well as that of other living things. Imanishi saw his disagreement with Darwin’s ideas as stemming from a fundamental difference in their respective standpoints: Darwin saw evolution as starting from the individual whereas Imanishi saw it as starting from the species, that is, not from the part, but from the whole, the One from which all living things arise. Or, more precisely, it is not that a change occurs in an individual organism, to then become generalised to the whole species. The two events take place simultaneously “When the species changes, all the individuals supporting it change as well.” To support this view, Imanishi give as examples two key events in the emergence of the human species: the move from quadrupedalism to bipedalism, and the apparition of language.

Bipedalism

What prompted the particular primates that grew into the human species to start walking erect on two feet? This is a hotly debated issue among anthropologists. One of the most common explanations is that when our ancestors came out of the forest into the savannah, grasses were so high, they could not see predators coming their way, and had to stand on their two back feet to get a better view.

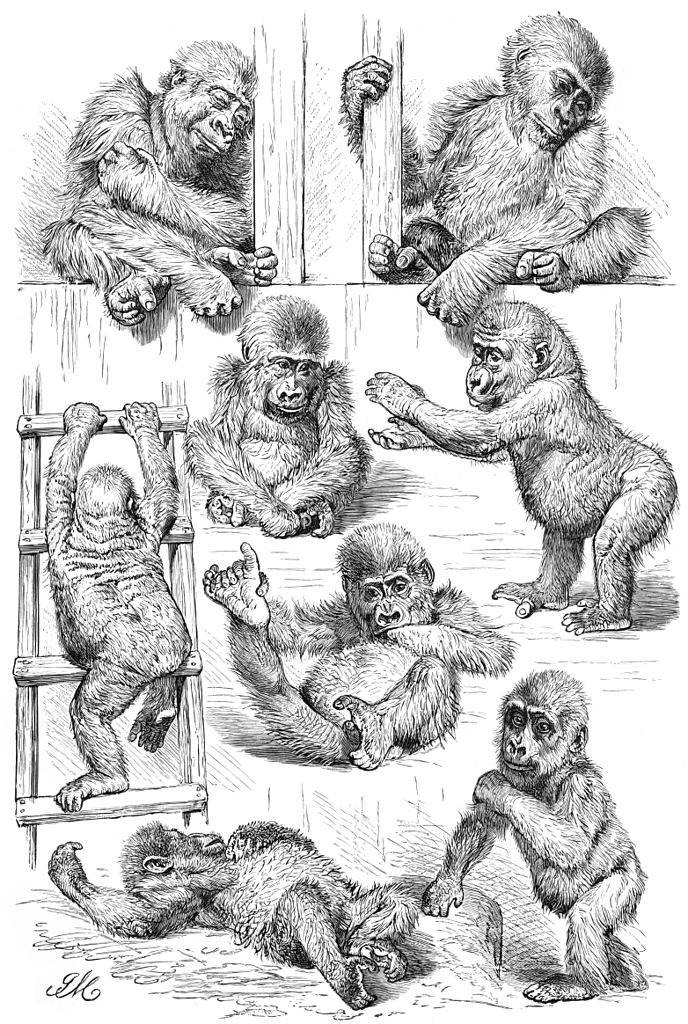

Carefully watching gorillas in the wild, Imanishi noticed that young gorillas often chose to walk on their hind legs, and were amazingly good at it, while the adults only rarely did, and, when they did, their bipedal walk was clumsy. This observation led him to postulate that bipedalism could have developed from neoteny, the retention of juvenile features in the adult. Neoteny has been found to occur in a number of species, and, with regard to the origin of human bipedalism, a number of anthropologists share Imanishi’s theory.

According to Imanishi, “the evolution from quadrupedalism to bipedalism is not a matter of daily microevolution, which can be explained in terms of development, it is a phenomena that belongs to macroevolution, requiring a reorientation.” He calls it a ‘new departure.” And it had to happen at the level of the whole group, as it would have been awkward if, in a group some individuals walked on two feet while others continued to walk on four!

But why did it happen? In a rather provocative fashion, Imanishi states that the human child had to stand up. Anticipating potential negative reactions to such a statement, Imanishi asks: “To change because one has to, why would this be strange? Isn’t your body changing because it has to?”

As an analogy, Imanishi explains that, though our body changes everyday, from one day to the next, we believe that it has remained the same. “Yet, since our childhood, we have bit by bit grown into adults, and then we have become old. We feel it in our flesh. If we do not change in the short term, we do change in the long term. It is exactly the same thing for evolution … Saying that evolution has changed because it had to, is to look at it, no longer as a product of mechanisms, but as following its own course.”

The origin of language

The development of language marked the second decisive step towards the emergence of our species. It provided Imanishi with a second example of a move that had to take place at the level of the species, rather than that of the individual. “Let’s suppose that … an individual with genius had started to speak fluently. Since language is language insofar as it is used to communicate, if others, at the same time, had not started to speak as well as he did, this would have had no meaning.”

Change takes place in all individuals at the same pace as it does in the species as a whole. Just as, every day, cells in my body are replaced by new cells, I do not change. I remain myself, and yet, at the same time I do change. I grow into an adult and then an old (wo)man. In this case, it is as if change followed its own course as it expresses myself as a subject.

Shutaisei as following one’s own course

In The World of Living Things, Pamela Asquith had translated shutaisai as the “autonomous subjective being,” and described it as the integrative activity of living things, the subjective activity that organises all perceptions into a meaningful world in which living things can make a living.

Forty eight years later, Imanishi still held shutaisei at the centre of his thought. And he then defined it as follows: “I keep my identity, the species keeps its identity, and yet we change … To change because we have to, or change through following our own course, this is what, once more, I would define as shutaisei [here translated by Berque as “subjecthood”] …If one recognises that an individual has subjecthood, and that a society has subjecthood, one had to recognise that the entire biotic society also has subjecthood.”

Reading the above, the reader must have, more than once, recognised many of the features of the modern systems theory. Imanishi, in fact, adopted the word “ecosystem” when it first arose in ecological circles. He, however, came to see it as a rather vague and abstract concept that did not adequately reflect the thrust of his view of the natural world. When referring to the entire world of species, he preferred to use the word “biotic society.” But the word that was really dear to him was shutaisei, the mind-like subjective activity that had created the myriad species out of one original cell. It was the notion of an evolution through “fitting-in” to maintain cooperation as the prime mover of evolution. While the neo-Darwinist theory of natural selection through competition has now colonised social, political and economic sciences, as well as our mindsets, Imanishi’s organic evolution through the integrative activity of a mind-like subjectivity resonates well with the holistic views based on the idea of a Living Earth currently being discussed among those involved in the environmental movement.

Sources

Imanishi Kinji – The World of Living Things (1941 – English translation 2002)

Imanishi Kinji – La Liberté dans l’Evolution (1978 – French translation 2015)

Nishida Kitaro – An Inquiry into the Good (1911 – English translation1990)

Nishitani Keiji – Religion and Nothingness (1962 – English translation 1982)