“The point at which emptiness is emptied to become true emptiness is the point at which each and every thing becomes manifest in possession of its own suchness” (Nishitani Keiji).

Meditation as a path to emptiness

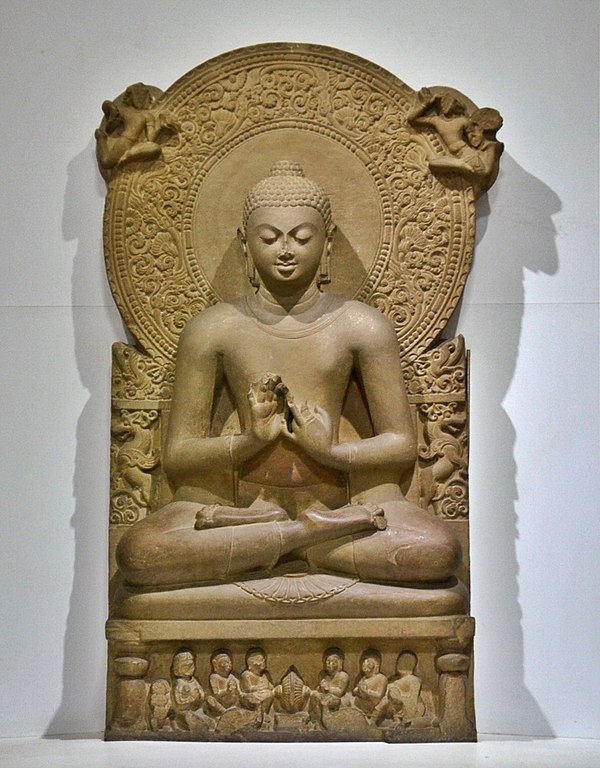

Sarnath Museum

For many Buddhists today, meditation is the practice whereby emptiness is realised and embodied in the way we encounter the world. This may be due in part to the popularity of Zen, but it is a fact that emptiness has been associated with the practice of meditation from the days of the Buddha. As a sramana, Gautama had learned and practiced an intensive type of meditation including eight levels of concentration (jhana). Meditation is one of the practices listed in the Eightfold Path and the Dhammapada.

Bret W. Davis tells us that the specifics of the relationship between meditation and emptiness have, however, evolved over time. “The Theravada has maintained that such states of meditative concentration (P. samatha) are merely preparatory to the more analytical forms of insight meditation (P. vipassana) which lead to liberating wisdom (P. panna). The Zen tradition, by contrast, holds [that] there [is] a more direct relation between non-discursive meditative concentration and enlightenment. Huineng in fact explicitly links – even identifies – meditative concentration (Skt dhyana) with liberating wisdom (Skt prajna).”

In other words, the concentration practice of samatha which, in Theravada, was seen as a training of the mind in preparation for the practice of the liberating analytical activity of vipassana, has become in Zen the practice leading directly to enlightenment. One could argue that both Dogen’s shikantaza and Linji or Hakuin’s koan practice are much more sophisticated concentration practices than samatha has ever been. The point here is that Theravada – as well as – Madhyamaka, tend to rely on analysis as a path to, at least, get glimpses of emptiness. And there is also truth in Zen’s stated reliance on a “pointing directly to [one’s] mind,” whereby one sees “into [one’s own true] nature and [thus] attain Buddhahood.”

The emphasis on analysis found in the Theravada and the Madhyamaka is congruent with their understanding of the cause of suffering. The Theravada saw it as our attachment to “things” which we erroneously believe to exist outside ourselves, and taught that we should cut our attachments in order to overcome our erroneous view of reality. Nagarjuna and his followers in the Madhyamaka revisited the issue from the side of the erroneous view, labeling it a “cognitive default,” a sort of trick consciousness plays on us, which leads us to see forms that are the mere constructs of our minds as “things” outside ourselves, and consequently causes us to crave for these “things,” and become attached to them. In both cases, analytical meditation was expected to allow us to “see through” the trick, and access the truth of the emptiness of all things.

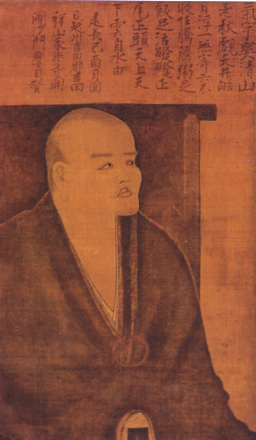

Zen, on the other hand, though owing much to Madhyamaka, was also influenced by Yogacara’s non-dual alaya-consciousness, which led to the concept of a non-dual buddha-nature within us, in the guise of a “radiant pure mind.” Huineng, whose Platform Sutra is regarded as the text that launched the Zen tradition, explicitly identified meditation and wisdom (prajna) when he said: “don’t make the mistake of thinking that meditation and wisdom are separate … Meditation is the body of wisdom, and wisdom is the function of meditation. And wherever you find meditation, you find wisdom .… What this means is that meditation and wisdom are the same … Don’t think that meditation comes first and then gives rise to wisdom or that wisdom comes first and then gives rise to meditation …” (Platform Sutra – Ch. 13). Whereas meditation had been for centuries associated with “seated meditation” – the familiar lotus posture with a straight back and hands resting on the knees – Huineng, argues that only deluded people think that “sitting motionless, eliminating delusions, and not thinking thoughts are One Practice Samadhi … If that were true, a dharma like that would be the same as lifelessness and would constitute an obstruction of the Way instead. The Way has to flow freely. Why block it up? The Way flows freely when the mind doesn’t dwell on any dharma.” Instead he proposes that “One Practice Samadhi means at all times, whether walking, standing, sitting, or lying down, always practicing with a straightforward [honest, sincere] mind.”

Meditation as engagement with the things and events of the world

With the new focus on the mind/consciousness came a frequent use of the metaphor of the mirror, as seen in the verse contest between Huineng and Shenxiu narrated in the Platform Sutra. Insofar as the Northern School did actually teach “gradual awakening” as described by Shenhui, this appears to have been its understanding of meditation: the mind had to be kept clean, it should not be allowed to gather dust.

As Davis notes, even though Huineng did not reject the metaphor of the mirror, he already went beyond the analogy with a mirror that needs to be cleaned – purified of all defilements – when he said, “Buddha nature is always clean and pure; where is there room for dust?” which, Davis tells us, was changed in the later standard version of the text to “Originally there is not a single thing” … “the remnant of an ontological duality between a pure and unchanging mirror and the impure and changing images reflected in it needs to be let go of; even the empty mirror needs to be emptied out into the world.”

After Huineng, “the teaching of the mirror mind increasingly gave way to the teaching that the mind – or rather the “no-mind”… is inseparable from the things and events of the world” (Yanagida Seizan, quoted by Davis).

At that point, the view of a passive “mirroring” occuring during meditation gave way to that of a dynamic process whereby the empty non-dual buddha-nature empties itself into the things and events of the world. It is as if the buddha-nature inspired us to meditate in order to actualise its enlightened nature in our very lives.

Soto Zen School – Shikantaza, opening up to the flow

Of the two main Zen schools that developed out of the Platform Sutra, the Soto Zen lineage seems to have followed most closely the ideal of blending meditation and everyday life. Dogen, its co-founder with Keisan, is known for his claim that “training is enlightenment,” which echoes Huineng’s claim that meditation and prajna are the same thing.

Of course, Dogen is also known for the transmission and elaboration of what could be regarded as a new type meditation he called shikantaza, “just sitting,” which, at first sight, seems to be the sort of motionless seated practice Huineng had rejected. Many Soto Zen teachers, however, insist that shikantaza is not meditation, in the sense of a (deliberate) “contemplation” of one’s thoughts, or an attempt at managing thoughts in one way or another, suppressing them or directing them. Shikantaza is an opening up to whatever takes place in the mind. It is a self-emptying to allow experiences and thoughts to flow freely. It is probably easier to do seated on the cushion, but we are invited to do it at all times, while engaging in our everyday activities, either in the routine of monastic life, or in the many tasks jostling for attention in the lives of lay practitioners.

Shohaku Okumura describes the practice of shikantaza as follows: “Just as the function of a thyroid gland is to secrete hormones, the function of a brain is to secrete thoughts, so thoughts well up in the mind moment by moment. Yet our practice in zazen is to refrain from doing anything with these thoughts; we just let everything come up freely and we let everything go freely. We don’t grasp anything; we don’t try to control anything. We just sit.” He also adds that it is a “very simple practice,” but it is also a “very deep” practice, and not an “easy” one. In such a practice, “we let go of the individual karmic self,” that which constructs the narrative, and allow “the true self, the self that is one with the entire universe [to] ‘manifest’.” This is the “presencing” Dogen referred to as genjokoan, “the presencing of things as they are.”

Dogen’s practice of “just sitting” is meant to allow “something akin to a “stream of awareness” in sync with the stream of ever-changing phenomena … and “a form of full engagement in which self and reality overlap and (ideally) fully interpenetrate” (Thomas P. Kasulis).

In the context of a culture where reality is assumed to be “change,” as life energy arising from the empty Dao flows through all things, shaping and animating them as it goes through them, it is especially important, as Huineng had said, not to “block” it by dwelling on any particular thing. Instead the mind must flow with it, and become “inseparable from the things and events of the world.” Dogen famously said: “Conveying oneself toward all things to carry out practice-enlightenment is delusion. All things coming and carrying out practice-enlightenment through the self is realization.” The second sentence encapsulates the self-emptying and opening up which will allow all things to, as it were, enter the self and enlighten it.

Rinzai Zen School – Koans to break through all dualities

The Rinzai Zen school, founded by Linji Yixuan “with its use of koans, teaches a more dramatic route through an intense state of meditative concentration …in order to cultivate the “great ball of doubt” (Davis). Koans are apparently irrational statements or stories presented as short exchanges between master and disciple, meant to shock the mind into “glimpses” (kensho) wherein the non-dual nature of the mind is directly intuited. Instead of being encouraged to “open up” to a “self-emptying,” Rinzai practitioners are called on “to break through all dualistic oppositions, of subject/object, inner/outer, pure/defiled, being/nothingness, speech/silence, etc …[the] Gordon knot [of duality] cannot be teased apart with the fingers of the intellect; it must be cut directly and holistically with the sword of intuitive wisdom” (Davis).

Both, however, are known to lead to the dissolution of dualities, the former through a blending with things as they present themselves, the latter by breaking through duality as it emerges again and again in one’s encounter with the world.

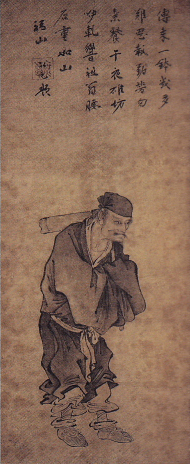

No-mind in the Action of Non-Action

With shikantaza and koans specifically designed to overcome duality, a return to the place of thinking – that is, the activity of creating conceptual “constructs” misinterpreted as “things” outside ourselves – had to be re-examined. No longer could it be simply dismissed as a “cognitive default,” as Nagarjuna had done. Davis writes: “What Huineng calls “no thought” (Ch wunian, Jp munen), and what later is often referred to as “no-mind” (Ch wuxin; Jp mushin), does not exclude thinking; rather,” quoting Huineng, “no-thought is not to think even when involved in thought …if you give rise to thought from your self-nature, then, although you see, hear, perceive, and know, you are not stained by the manifold environments, and are always free.”

What is meant by “no-mind” is the ability to “flow” with things and events, without “lingering in” any of them. “No-mind is akin to what athletes or musicians experience when they are “in the zone,” utterly absorbed in an activity of the here and now (including when the “here and now” involves remembering, planning, or otherwise thinking of the “there and then”). A Zen master, however, would live all of life in the zone, whether listening or laughing, crying or dying, and would be able to shift effortlessly between different activities, at once absorbed in and yet unattached to any of them” (Davis).

Davis argues that this is also true of intellectual activity: “Not only when one is absorbed in a train of thought, also when one effortlessly switches one’s focus from one train of thought to another, this too is an instance of no-mind.” No-mind is not “thoughtlessness.” To get a thoughtless mind, you need to deliberately block all thoughts. But then you get a blank vacuum, not a free flow of thoughts. Thomas P. Kasulis described no-mind as “a heightened state of non-dualistic awareness in which the dichotomy between subject and object … is overcome.”

Davis’s translation of no-mind as wuxin, one of the wu forms widely used in Daoism, along with wuwei (non-action), wushi (non-interfering when going about one’s business), wuming (naming without fixed reference) and others, makes it clear that wu does not refer to the objective absence of something, but to the absence of deliberate interference with a process. A more explicit translation of wuxin would be “unmediated thinking and feeling.” Xin is usually translated as “heartmind,” hence the dimension of “feeling.” Feeling here refers to a natural, spontaneous, arising thought in the sense of intuitive insight.

“To think and act in a state of no-mind is to be at once free and natural; it is to exist in a state of natural freedom” (Davis). Wuwei is a “naturally free action” also referred to as the “action of non-action” – wei-wu-wei – and again, it “indicates not a lack of action but rather pure activity, in other words, activity that is empty of willfulness and artificiality” (Davis).

All these apparently negative terms – no-mind, non-thinking, non-action – refer to processes which are allowed to occur naturally, and are to be taken as “the affirmation of a liberated and liberating way of life.” Davis suggests that such words as “freedom” or “openness” would be better at conveying what it means to think and live from the standpoint of no-mind.

“The field of sunyata is nothing other than the field of the Great Affirmation” (Nishitani)

Davis said above that “no-mind is akin to what athletes or musicians experience when they are “in the zone,” adding this refers to a state where one is “at once absorbed in and yet unattached” to any activity.

The same blend of absorption and non-attachment allowing a heightened positivity towards all things is found in Nishitani’s description of the field of sunyata as the field of the Great Affirmation. Nishitani explains: “The double negation of things and self results in a restoration of both things and self on the field of emptiness, which could be called “the field of ‘be-ification’ or, in Nietzschean terms, the field of the Great Affirmation, where we can say Yes to all things.” In a more traditional language, Nishitani also writes: “The point at which emptiness is emptied to become true emptiness is the point at which each and every thing becomes manifest in possession of its own suchness.” Each act of consciousness enacts the self-emptying of emptiness into the empty phenomena that we see as the things of the world. It could also be said that the self-emptying, or self-negation, of a dynamic emptiness is the “activity” or “function” of consciousness, which we live as the affirmation of phenomena as phenomena. “Impermanence is the Buddhahood” (Dogen).

Sources

Bret W. Davis – “Forms of Emptiness in Zen” (Research paper)

Red Pine (Bill Porter) – The Platform Sutra – The Zen Teaching of Hui-neng (2006)

Shohaku Okumura – Realizing Genjokoan, The Key to Dogen’s Shobogenzo (2010)

Thomas P. Kasulis – Engaging Japanese Philosophy (2018)

Thomas P. Kasulis – Zen Action, Zen Person (1981)

Keiji Nishitani – Religion and Nothingness (English translation 1982)

More detailed presentations of the teachings developed by the different schools of Buddhism are available on the other pages of this website. For more information on Nishida Kitaro and Nishitani Keiji, please refer to my other website dedicated to the Kyoto School of Philosophy https://thekyotoschoolofphilosophy.wordpress.com