The concept of emptiness has been a cornerstone of Buddhism throughout its history, during which it has taken many forms, as the term was often misunderstood and required repeated clarifications by successive generations of Buddhist scholars and practitioners. On this page, I follow the evolution of this concept from the philosophical standpoint. On the next page, I look into the impact of its evolution in terms of the practice.

Anatman – the self is empty of own-being

According to tradition, the concept of emptiness was introduced in the context of the Buddha’s challenge of the Upanisads’ doctrine of atman, the individual self, said to share the essential nature of brahman, the Cosmic Self, the uncaused, unchanging, substratum that was the original cause of all that exists. Challenging atman’s existence was therefore paramount to challenging brahman’s ultimate existence, a revolutionary move indeed, perhaps not unlike Nietzsche’s announcement that “God is dead.” It is said that the Buddha kept silent when asked directly about atman and brahman, but he did assert that, based upon his meditative experience, he had come to see that there was no unchanging atman within us, what I called “my self” was neither unchanging nor substantial – it was therefore called “anatman,” translated as “no own-being.” It was also called “no-abiding self” to highlight the fact that it was at each moment the product of changing conditions – in an apprehension of reality experienced as taking place here and now. There was indeed a subjective experience, but there was no lingering entity remaining the same behind it. That experience of subjectivity was later described as composed of five “heaps” (Skt skandhas) similarly devoid of substantial existence, and instead, the products of conditions.

What the Buddha taught, however, was not new. It was a revival of the shamanistic worldview based on the insights of the yogis Gautama had met and learned from when he joined the sramana communities in the forest. These were the descendents of the refugees from the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation after its collapse, and they, like the Daoists in China, the Shinto in Japan, as well as the native Americans, and all other so-called “traditional” (that is, “pre-literate”) peoples, saw the world as alive with interconnected forces, with which one had to interact, rather than control and exploit.

Gombrich notes that, with anatman, the Buddha “was refusing to accept that a person had an unchanging essence,” adding that “it was something very few westerners have ever believed in and most have never even heard of.” Yet, anatman as the lack of abiding (unchanging) self, often shortened to “no-self,” has again and again led to the erroneous belief that Buddhism teaches that we had no selves.

The Prajnaparamita Sutras and Nagarjuna

In the centuries following the death of the Buddha, Abhidharma scholars undertook a systematisation of the teachings of the Buddha. As Bret W. Davis explains, they saw themselves as “taking up where the Buddha left off when he analyzed the self into five skandhas …They broke each of these down further until they reached what they considered to be the ultimate physical and mental constituents of reality, which they called dharmas. Whether these dharmas were understood to be permanent (as in Sarvastivada Abhidharma) or momentary (as in the Sautrantrika Abhidharma), they were taken to be real existents, the atomistic building blocks of the universe, so to speak.”

In parallel with this development, the many versions of the Prajnaparamita sutras had been composed to support the practice of Buddhist monks where emptiness occupied centre stage. The same preoccupation with a clarification of the concept of emptiness prompted Nagarjuna to revisit the Buddha’s claim that the self and all things were empty of “own-being.” This led him to criticise what he saw as a philosophical drift, and articulate the equation of sunyata (emptiness) with dependent origination. In Davis’ words, “There are no substantial building blocks of the universe; nothing has independent existence; everything depends for its existence on causes and conditions; and everything is essentially interconnected. This radical teaching of the emptiness of own-being lies at the core of the Prajnaparamita Sutras and Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka school of thought, which established the initial philosophical basis of the Mahayana tradition.” Nagarjuna’s own famous statement reads: “It is dependent origination that we call emptiness. It is a dependent designation and is itself the Middle Path” (Nagarjuna, Mūlamadhyamakakārikā). The statement could not be clearer: emptiness is dependent origination, i.e., interconnectedness. To avoid any misunderstanding, Nagarjuna specifically asserted that emptiness as he defined it, did not mean that nothing exists at all on any level. Things did exist, but as conditioned, not as inherently existing independent substances. The message, however, was not always properly heard, and a belief remained among Buddhist sanghas as well as the general public, that Buddhism claimed that all the things we see are not really real, because they are the products of conditions, and would disappear when the conditions come to an end.

Yogacara and the Alaya-consciousness

While the disciples of Nagarjuna in the Madhyamaka school elaborated on the equation of emptiness with dependent origination, the Yogacara school, founded in the 4th century by Asanga, a monk, and his more philosophically inclined half-brother Vasubandhu, engaged in a parallel investigation of the concept of emptiness. Their starting point was a concern that the Madhyamika view of emptiness as dependent origination left “phenomena supported by nothing but other unsupported phenomena” (Peter Harvey). In other words, it was too nihilistic.

They consequently embarked on a study of the “mechanics of consciousness.” In the early Abhidharma “consciousness (Skt vijnana) …was seen to be of seven types: consciousness related to each of the five physical senses, mind-consciousness, and mind-organ (Skt manas) with the latter processing the input from the senses” (Harvey). Yogacara took these layers to merely referring to “the surface of the mind,” and added a deeper eigthth layer. “Devoid of purposive activity and only indistinctly aware of objects, it is an underlying unconscious level of mind known as alaya-vijnana, the “storehouse consciousness” (Harvey). This deeper consciousness “stored” the accumulated (good and bad) karmic material shaping the way we see the world.

A lengthy controversy erupted as the Madhyamikas criticised the scholars of the Yogacara and Tathagatagarbha schools for having “relapsed” into substantialism, now seen in terms of a non-dual “unconscious” level of consciousness taken to be a substratum underlying phenomena.

To be fair, the Yogacara scholars did accept the criticism about the apparent substantiality of the alaya-consciousness. Their argument – that their teachings, as all Buddhist teachings, were only skilful means – though correct to a point, failed to satisfy the purists who insisted on a total absence of anything underlying – whether sub-stance or sub-stratum – behind conditioned phenomena.

Tathagatagarbha – the non-dual Buddha-nature within us is interpreted differently in India and in China

In the Prajnaparamita sutras, the “brightly shining citta” within ourselves appears as the “thought of awakening” (bodhi-citta), the heartfelt aspiration to embark on the Bodhisattva path. It is, however, in the Tathagatagarbha Sutra that the concept of buddha-nature was fully developed. The word Tathagata means “thus gone” or “thus come.” It was originally used when referring to the historical Buddha. In Mahayana it refers to Buddhahood itself. Garbha means either “embryo” or “womb.” It refers to the presence within us of a potential Buddhahood. It is said in the Lankavatara Sutra that “the alaya-vijnana is also known as the Tathagata-garbha”(Harvey). The fact is that the scholars of both schools were similarly concerned about the way Nagarjuna’s equation of emptiness with dependent origination left “phenomena supported by nothing but other unsupported phenomena” (Harvey).

Francis H. Cook notes that the notion of womb, embryo or seed of Buddhahood was regarded in the Indo-Tibetan cultural zone as “merely a seed, the undeveloped source or cause of the fully grown fruit of Buddhahood.” A lengthy training was required to bring this seed to full Buddhahood. In China, however, it “often came to be seen as a pre-existent reality waiting to be uncovered” (Harvey). Steeped in the view of a non-dual Dao also conceived as a womb (in the sense of source and flow of life giving shape to all things), Chinese Buddhists were not concerned about the need to avoid confusion with Brahmanical essentialist views! In that new cultural context, the concept of buddha-nature escaped considerations of substantiality. Instead, in keeping with the East Asian apprehension of reality as change, buddha-nature, together with its association with the alaya-consciousness, was soon redefined as non-dual prajna, and explored in terms of “process” or “activity.”

The Huayan School

Though one of the most influential schools in East Asia, the Huayan school is still relatively unknown in the West. Encapsulated in the metaphor of Indra’s Net, “a massive net representing the universe, in each knot of which lies a jewel reflecting all the others” (Cook, quoted by Davis), its core teaching of “mutual identity and interpenetration of all phenomena” first appears to be an expanded interpretation of dependent origination, emphasizing the relation between the part and the whole, as well as the relation between each part. It is said that, not only does the whole include the part, but the part includes the whole. This seemingly modest alteration reflects a momentous shift in the way reality is apprehended. Dependent origination was meant to describe how “things” did not exist independently. Mutual identity and interpenetration of all phenomena, with each part necessarily including the whole, turns each part into a function of the whole. Take, for instance, a pair of eyeglasses, an example used by B. Allan Wallace in one of his online lectures, disassemble it into its parts – the frame, the lenses, the hinges, the temples, the ear pieces, and lay them on the table, do you still have eyeglasses? You definitely cannot put them on to read the text in front of you. You only have parts of a pair of eyeglasses. To have eyeglasses that enable you to see, the parts need to be re-assembled, and “function” as eyeglasses. With this switch from “thing” to “function,” a dynamic dimension has been introduced.

In Madhyamaka texts, dependent origination has been called upon to explain how phenomena including the self, come about as the products of conditions, arguing that seeing them as inherently independent substances resulted from a “cognitive default.” Because the Indian Brahmanical mainstream culture was based on an essentialist/substantialist worldview, a similar (ontological) language had to be used in order to challenge it. In the Huayan apprehension of reality as a dynamic network, or system, of interconnected relations, a positive understanding of how the world works comes into view. Davis writes that, in the Huayan worldview, “each phenomenon of the universe contains, and is contained in, all the others. No phenomenon could be what it is without the support of every other, and the universe could not be what it is without the support of each phenomenon.” While, for the Yogacara and the Tathagatagarbha, phenomena had appeared to be “supported by nothing but other unsupported phenomena,” with the introduction of a dynamic dimension, phenomena are supported by all other phenomena.

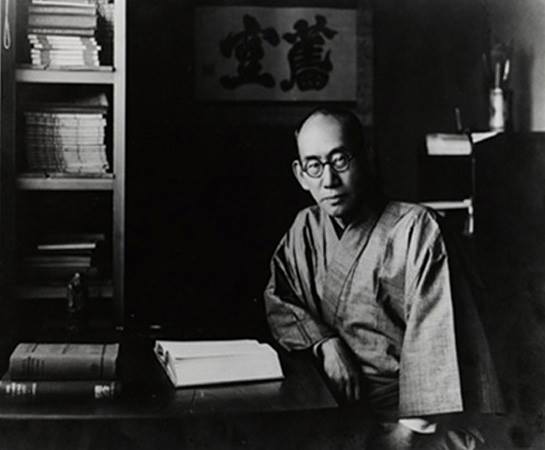

Nishitani Keiji: the field of sunyata is a “field of force” emanating from a system of circuminsession

In the modern era, the thinkers of the Kyoto school, whose philosophical inquiries were pursued in parallel with a Zen practice, have deepened this dynamic view of emptiness as a system of interconnectedness. Nishitani elaborated on the Huayan concept of reality when he described what he calls “a system of circuminsession or circuminsessional interpenetration.” Nishitani writes:

“Not a single thing comes into being without some relationship to every other thing … On [an] essential level, a system of circuminsession has to be seen here … In this system each thing is itself in not being itself, and is not itself in being itself … To say that a thing is not itself means that, while continuing to be itself, it is in the home-ground of everything else. Figuratively speaking, its roots reach across into the ground of all other things and help to hold them up and keep them standing. It serves as a constitutive element of their being so that they can be what they are, and thus provides an ingredient of their being. That a thing is itself means that all other things, while continuing to be themselves, are in the home-ground of that thing; that precisely when a thing is on its own home-ground everything else is there too; that the roots of every other thing spread across into its home-ground … It enables us for the first time to conceive of a force by virtue of which all things are gathered together and brought into relationship with one another, a force which, since ancient times, has gone by the name of “nature.”

What Nishitani calls the “field of emptiness,” is a “field of force.” “The “force” … by virtue of which all things make one another exist – the primal force by virtue of which things that exist appear as existing things – emanates from this circuminsessional relationship.” Thanks to this force, Nishitani says, using a term borrowed from Heidegger, the world “worlds.”

As Davis notes, talking about a field of force in the 1960s when Nishitani was writing Religion and Nothingness, brought to mind what science calls an electromagnetic field, or even a quantum field, and we must keep in mind that any word we use is but a metaphor, that is, a skilful means. It is an irony of history that the language of dynamics, energetics, or simply “activity,” is also that of the East’s own ancient , but still alive, traditional view of the world. Davis recalls that the word “field” had already been used by Ikkyu, a Zen Buddhist monk of the 15th century, when he spoke of emptiness as “a formless “original field” from which everything arises and to which everything returns.” That view obviously reflected the traditional view of the Dao, out of which all things arise and to which they return. Nishitani himself says that this force “since ancient times, has gone by the name of “nature.”

Nishida Kitaro: basho, self-contradictory identity and the self-determination of absolute nothingness

Nishitani’s field of emptiness also echoed the notion of “basho,” developed by Nishida, the founder of the Kyoto School, and Nishitani’s mentor. Nishida had also sought a support for “unsupported phenomena” in the guise of a spatial metaphor, which, since he had set himself the task of using the terminology of Western philosophy, he found in the Timaeus, where Plato speaks of chora, in the sense of a “receptacle or matrix”, not unlike the Dao, as a place (topos) out of which being arises out of nonbeing, which he translated in Japanese as “basho.” Basho is the self-conscious self, the place where, through each act of consciousness, absolute nothingness – the formless – self-determines as the forms of phenomena. Nishida writes: “That I am consciously active means that I determine myself by expressing the world in myself … The world that, in its objectivity, opposes me, is transformed and grasped symbolically in the forms of my own subjectivity. But this transactional logic of contradictory identity signifies as well that it is the world that is expressing itself in me.” The world as it appears in our consciousness is “the many as the self-negation of the One and the One as the self-negation of the many.”

Note that Nishida’s use of the term “absolute nothingness” was motivated by a concern that the word “emptiness” could have misled his readers into thinking that his philosophy only applied to practitioners of Buddhism having achieved a particular “state” of consciousness.

Robert E. Carter explains the logic of contradictory identity – also referred to as the “self-identity of absolute contradictories,” or, simply as “the unity of opposites”- as follows: “The one is self-contradictorily composed of the many, and the many are self-contradictorily one. The world can be viewed in two directions – the double aperture – and its unity is not the unity of oneness, as the mystic would likely express it, but the unity of self-contradiction. It is both one and many; changing and unchanging; past and future in the present. Nishida’s dialectic has as its aim the preservation of the contradictory terms, yet as a unity.” Though Nishida had worked out the concept of self-contradictory identity in the context of his own philosophical inquiry, in the last five years of his life, through conversations with his lifelong friend D. T. Suzuki, he came to see it as a close parallel to the Prajnaparamita’s logic of sokuhi, “the absolute identification of the is, and the is not. In symbolic representation: A is A; A is not-A; therefore A is A. I see the mountains. I see that there are no mountains. Therefore I see the mountains again, but as transformed. And the transformation is that the mountains both are and are not mountains. That is their reality.”

The above is, of course, a reference to the well-known epigram by Qingyuan Weixin, where it is said, in a nutshell: As a novice, I believed that mountains and waters were inherently existing entities as given in ordinary self-consciousness; after years of training, I realised that “mountains” and “waters” were just names, and not inherently existing entities outside my mind; when I attained awakening, I again saw that mountains and waters were indeed real, but “lined with nothingness,” both real objects and names at once, to be seen through the “double aperture,” which is two and, at the same time, one.

Even though, when describing sokuhi as a logic of self-contradictory identity, Nishida uses the word “logic,” he does not see “logic” as a mere static principle the way Aristotle saw his logic of “non-contradiction” as a principle of reason. Because for Nishida, as for other East Asian thinkers, reality is the unfolding of change as experienced here and now, there is a dynamic dimension in that logic. Absolute nothingness “is the dynamic principle of affirmation by way of absolute self-negation” (Davis).

Nishida sees absolute nothingness as the activity of self-negation in terms of the “self-determination of the dialectical world,” a world which continually moves according to the principle of “from created to creating.” “From the created to the creating (from creatus to creans), from the formed to the forming is how [Nishida] describes our situation: we are created by our inheritance and our environment, and yet, we also are capable of re-shaping our environment and of altering our inheritance both for ourselves, and for our offspring” (Carter).

Emptiness is the activity of interconnectedness

Since the word “ontology” literally means the discourse (logia) on being (onto), Davis suggests that the Buddhist view of ultimate reality as emptiness should be called a “kenology” (from the Greek kenotes meaning emptiness). But the final definition of Buddhist emptiness must give pride of place to the notion of interconnectedness. Whether you call it “dependent origination,” “mutual identity and interpenetration of all phenomena,” “circuminsessional interpenetration,” or “self-contradictory identity,” this is what positively defines what the word emptiness stands for in Buddhism, where it is most clearly elucidated in Zen. “The self-emptying of emptiness occurs as the interdependent origination of all things” (Davis). Emptiness as the activity of self-emptying is the dynamic interconnectedness of all phenomena.

Sources

Richard F. Gombrich – How Buddhism Began (1996)

Bret W. Davis – “Forms of Emptiness in Zen” (Research paper)

Bret W. Davis – “The Kyoto School” – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Peter Harvey – An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practice (2013)

Francis H. Cook – Hua-yen Buddhism – The Jewel Net of Indra (1977)

Keiji Nishitani – Religion and Nothingness (English translation1982)

Kitaro Nishida – Last Writings (English translation 1987)

Robert E. Carter – The Nothingness Beyond God (1997)

More detailed presentations of the teachings developed by the different schools of Buddhism are available on the other pages of this website. For more information on Nishida Kitaro and Nishitani Keiji, please refer to my other website dedicated to the Kyoto School of Philosophy.