To be is to inter-be. You cannot just be by yourself alone. You have to inter-be with every other thing.

Thich Nhat Hanh

In his latest book, Ecodharma – Buddhist Teachings for the Ecological Crisis (2018), David R. Loy writes: “Buddhism is not only what the Buddha taught but what the Buddha began – and we keep the tradition alive by keeping it relevant to our situation.” Newcomers to Buddhism usually assume that they must start with getting acquainted with the early texts, said to be “what the Buddha taught” as they appear in the Pali Canon. This is certainly helpful – and we will also start with a these – but it would be a mistake to stop there. On one hand, we would miss out two millennia and a half of meditative experience and inquiry by Buddhist teachers keen to refine the original insights of the Buddha. On the other, we would have failed to realise that what the Buddha had intended to teach is a practice allowing each of us to cleanse our minds of self-centred attachments, so that we, too, can follow the path that was walked by the Buddha, and see for ourselves “things as they are” from the “standpoint of the heart-mind,” in order to get an insight into “what needs to be done” in the particular situation we happened to be in. As far as we know, there was no ecological crisis at the time of the Buddha, so we will not find any particular teaching about this issue in early Buddhist texts. Yet, Buddhism can indeed help us cope with the crisis, and Loy’s book explores how it can do this.

The Four Noble Truths: Dukkha, craving and the quest for solidity

“Existence is suffering

Craving is the origin of suffering

Freedom from craving is the cessation of suffering

The Eightfold path is the way to the cessation of suffering.”

Though we often despair at the state of the world, it is usually our own “suffering” that drives us to embark on a Buddhist practice. The word “suffering,” which is the traditional translation for dukkha does not quite express what we feel, which could be best described as a feeling of dissatisfaction, uneasiness, a sense of “lack” pervading our lives, uncertainty about who we are, and anxiety about the role we are meant to play in the world. In the Second Noble Truth, the Buddha says that “craving is the origin of suffering.” What we crave for is what we perceive as things existing in a world that is outside of us. We believe that these things really exist independently of ourselves because, as children, our parents and teachers have taught us that it is what they are, at the same time as telling us what their names are. At the same time, we have come to believe that we have a “self,” because we also have a name – an identity. Yet, somehow, we feel that this self lacks solidity, and does not truly exist. Part of this takes the shape of a concern about our physical mortality. But even when we are young and healthy, we are plagued with a worry about the need to constantly reassert the existence of the “self” as it seems to dissolve if we don’t.

The reason for this predicament is, of course, that neither our selves nor the things of the world exist, as we see them, independently of our consciousness. Not that they do not exist at all, but they do not exist the way we see them. The way we see them is conditional on our circumstances, and a these change at each moment, they have to be recreated, as it were, repeatedly restored to existence.

What is worse is that we often believe that we alone experience that unease, everybody else seems to know who they are, and what they want to do. Well, we are not alone. This sense of inexistence is a downside of the human condition. Because we possess a sophisticated reflective consciousness, we relate to the world and to ourselves through a set of representations causing the world and ourselves to appear as a multitude of discreet entities separate from each other and from us. Specifically, as Charles Eisenstein explains, we see ourselves as separate from a world that does not care about us, and we believe that we need to control that world for sheer survival. That includes controlling others as well, and the reason some people appear to feel secure is that they have already wrapped themselves up inside a solid armour! More often than not they have taken refuge in the mainstream worldview, or a particular group or ideology to beef up their own sense of existence!

With Mahayana, focus turned to the “mechanics of consciousness”

So, if both the self and the things of the world only exist in our consciousness, what is there behind the screen of our representations to which we appear not to have access to? In the Brahmanical mainstream cosmology at the time of the Buddha, it was an unchanging, formless Absolute referred to as Brahman. In other words, what truly existed was equated with what was permanent. It is this equation that the Buddha rejected when he claimed that his experience of intensive meditation has failed to confirm the existence of such an unchanging self. Since in Brahmanical thought, the individual “small” self (atman) had been taken to share the divine unchanging nature of the Cosmic Self (Brahman), no unchanging atman also meant no unchanging Brahman. Both the self, and ultimate reality as such, were “empty” of independent unchanging existence.

Revisiting the teachings of the Buddha, Nagarjuna (150-250 CE) embarked on a systematic analysis of the way we have come to “add” (solid) substance to what we claim to know, and concluded that our belief in the independent existence of both self and things was due to a “cognitive default.” Because our hearts crave for solidity, our minds project substance onto our representations. A few centuries later, Vasubandhu and the other thinkers of the Yogacara school explored in great detail the active layers of our consciousness, and stated that the process whereby consciousness, as it were, gives birth to our view of reality arose from an underlying “storehouse consciousness,” (the alaya-consciousness). Itself “only indistinctly aware of objects,” this deeper layer stores our “karmic seeds” and projects the karmically shaped representations that we mistake for things existing outside ourselves (Paul Harvey).

Indra’s Net

With its entry into the Chinese cultural zone at the beginning of the first millennium, ideas about the Dao merged with Buddhist emptiness (sunyata). The Chinese had also seen the Dao as “empty,” but more in the sense of a fertile dynamic field giving rise to life, and sustaining it by a set of laws (li), of which the interaction between yin and yang is the best known. At that point, emptiness took a dynamic dimension. It was no longer a lack of being, but rather a source of life.

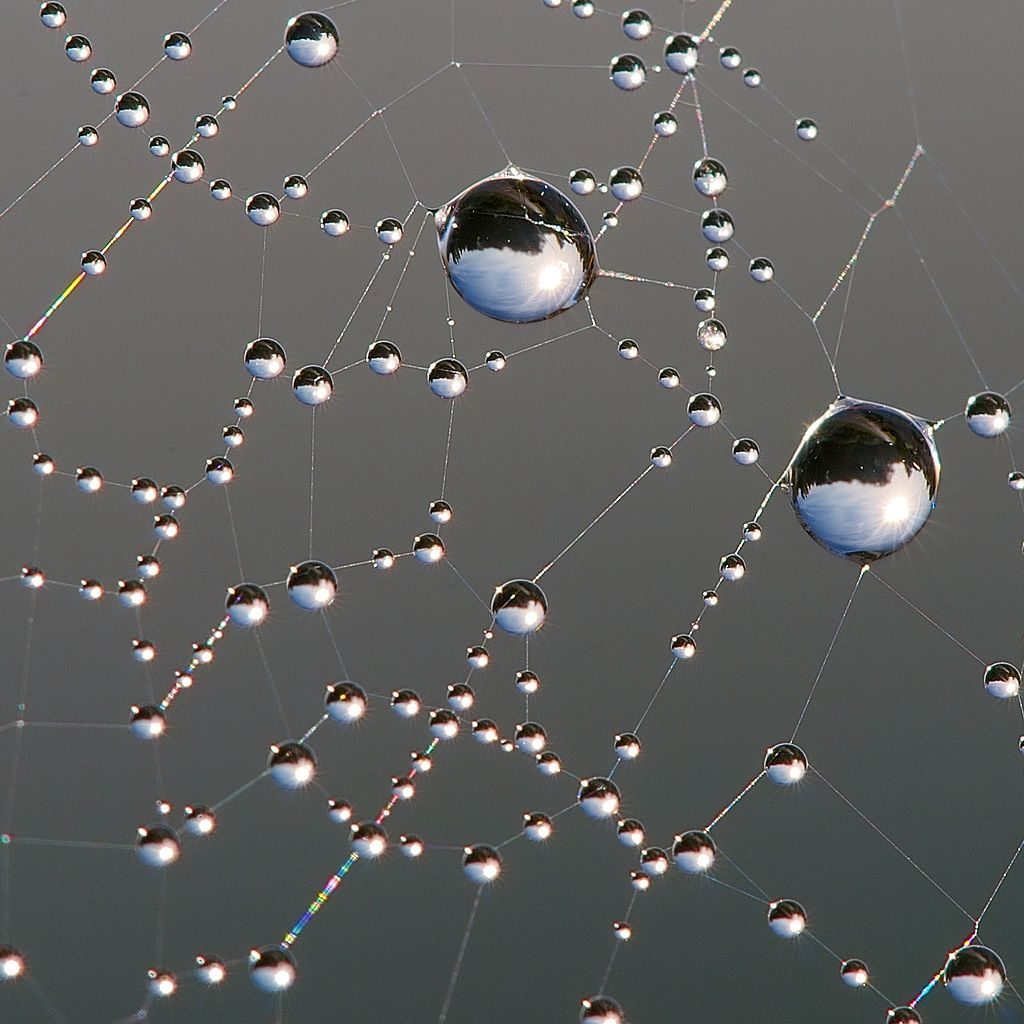

Starting around the 7th century, the Huayan school expanded on the notion of emptiness as a dynamic system of laws, and worked out the doctrine of “mutual identity and interpenetration of all phenomena,” a holographic worldview illustrated by the metaphor of Indra’s Net. The world of phenomena was compared to a wonderful net stretched in all directions on which one has “hung a single glittering jewel in each “eye” of the net, and since the net itself is infinite in dimension, the jewels are infinite in number.” On the surface of each jewel, “there are reflected all the other jewels in the net, infinite in number. Not only that, but each of the jewels reflected in this one jewel is also reflecting all the other jewels, so that there is an infinite reflecting process occurring” (Francis H. Cook). We have here a radical description of the interdependence of the parts of a system, each part dependent on every other part, and all parts dependent on the whole, and in that sense, “including” the whole, while the whole itself depend on all its parts. Another, perhaps more familiar illustration, would be the way the proper functioning of our bodies depends on that of each of its organs, while each organ depends for its health on all the health of other organs, and on the health of the whole body. So not only the whole includes the part, but the part also includes the whole. This is what is now described as an “ecosystem.”

This is not to say that either Daoism or Buddhism single-handedly discovered the interconnectedness of all aspects of nature, including humans. Before it had shaped Daoism, this view had been shared by many traditional societies based on foraging and horticulture, and can still be found, for instance, among the cultures of native Americans. In most parts of the world, however, it has been displaced by the emergence of what we call “civilisation,” marked by its monumental architecture, a fitting symbol for its ideology of expansionism and domination. These ideologies launched the frightening quest to be more through having more and controlling more, that underlies what Eisenstein calls the Story of Separation. The Buddha’s quest had been an attempt at restoring this ancient worldview of interconnectedness. Likewise, this worldview is currently being rediscovered in contemporary science and ecology – systems thinking and complexity theory, but also theory of relativity and quantum mechanics.

From Separation to Interbeing

Though not claiming to be a Buddhist, Charles Eisenstein acknowledges a strong Buddhist influence on his thought, best summed-up as a path of understanding and practice that can lead us from the Story of Separation – that which has led unenlightened humankind to the quest for being and domination, with the catastrophic consequences we are now witnessing – to the Story of Interbeing, using the term coined by Thich Nhat Hanh to refer to the universal interconnected network of dynamic relationships described by the Huayan school.

In Eisenstein’s own words “the Story of Separation essentially says that what you are is a separate individual among other separate individuals in this objective reality that has fundamentally nothing to do with you.” In the secular language of the world we now inhabit, “we are, these kind of bubbles of psychology bouncing around the world, in competition, fundamentally, with other individuals. Because if I am separate from you, then, more for you is less for me. And, the forces of nature, outside of ourselves … they are not intelligent; they are not conscious. It’s just a bunch of protons, neutrons, and electrons bouncing around out there according to mathematically determined forces.”

To this world determined by competition and the will to dominate, he opposes a world based on the realisation of our interbeingness with other life-forms. “‘Interbeing’ is a very natural term. It means more than Interconnection or Interdependency, which kind of suggests separate selves ‘having’ relationships. Interbeing is more of an understanding that we are relationships, that my very existence depends or draws from or includes your existence. So my well-being is intimately connected to your well-being or to the well-being of the river, the ocean, the forest, people across the world, and so forth, because I am not really separate from you … I know that whatever I do to the world will come back to me, somehow” (Eisenstein).

Whereas Thich Nhat Hanh, who in his native Vietman had attempted to stop the war between the US and the Vietcong, had focused his teachings on peace, Eisenstein presents his as a path out of the ecological crisis. This is the focus of his latest book – Climate-A New Story (2018) – but his earlier books, especially Sacred Economics, and The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know Is Possible, also examine what societies and economies would be like if one used the principle of interconnectedness to rebuild a civilisation that would be enduring, and ensure not only our survival, but also that of the amazingly complex and stunningly beautiful life-forms of the natural world we are part of.

On this point, Eisenstein uses the notion of “buddha-nature” (though he does not explicitly refer to it by its Buddhist name). What Mahayana Buddhism terms the buddha-nature is an elaboration of the concept of Bodhicitta – the thought of enlightenment – believed to exist within all of us – which is the starting point of the Bodhisattva path. Developed by the Tathatagarbha School – garbha means “womb” or “embryo” – of Buddhahood, it became widely adopted by most schools of Mahayana under the name of “buddha-nature.” Rather than focusing on suffering, as the Buddha had done, it points to our inborn potential for awakening: each of us is already enlightened, and we only need to see through the delusive screen of our constructs to realise it. What Eisenstein calls “the more beautiful world our hearts know is possible” is a more concrete formulation of that inherent insight. It is what we see when we ask ourselves, “Who am I, really? Am I that person trying to pursue my own self-interest, no matter what, even if it means children going hungry, and whole swathes of land turning into deserts? Am I really that person, or wouldn’t I really prefer a life in harmony with all life-forms, sharing with, and nurturing, all that exists?”

Ecodharma

After a lifelong study, practice and teaching of Zen, as well as an academic career in Buddhism and philosophy – and many publications to his name – David Loy has similarly come face to face with the ecological crisis. For him too, the crisis is more than an issue concerning the climate, more than the release of greenhouse gases caused by our excessive use of fossil fuels, more even than the deforestation and loss of biodiversity that prevent nature from storing carbon as it should. Loy shows that the causes of the ecological breakdown – our obsession with control and domination – are the same as the causes of our individual dukkha – our sense of insecurity due to a lack of solid being – which Buddhist practice is designed to overcome. The ecological crisis is an externalisation of our own existential predicament, and the path of practice leading to collective awakening required to create a unified ecological action parallels that which practitioners have used to achieve individual awakening.

Loy recognises, however, that contemporary Buddhists have been slow at engaging with the crisis. This, he believes, is associated with the way Buddhist teachings have been presented in the past, which continues to shape the understanding of practitioners, even in the West, because Western practitioners are still taught through traditional texts reflecting ancient Eastern cultures. In Theravada texts, the practice is described as leading to an escape from the cycle of rebirths, that is, a transcending of worldly life. In the Mahayana sutras, the emphasis is on sunyata as the ultimate reality, and a world arising from, and maintained by, the Dao, which is regarded as perfect as it is. Though this was an altogether more positive apprehension of the world, it too had discouraged any attempt at what could be misconstrued as an interference with the laws of nature. Daoism explicitly trusts nature as being able to take care of itself. What we are called to do is simply learn from nature, and flow with life – in other words, adjust to the world. Curiously, both the wish to escape incarnated life, and the acceptance of incarnated life as perfect, have led to the same lack of interest in social, political and economic reform.

Rather than emphasizing such traditional notions as no-self (anatman) and emptiness (sunyata), Loy talks about the need to deconstruct the self, and to reconstruct it. Rather than insisting that form is emptiness, Loy reminds us that in the well-known formula of the Heart Sutra, emptiness is form. “The Buddha did not teach – nor does his life demonstrate – that nonattachment means unconcern about what is happening in the world, to the world. When the Heart Sutra famously asserts that “form is not different from emptiness,” it immediately adds that “emptiness is not other than form.” And forms – including the living beings and ecosystems of this world – suffer.”

The Bodhisattva as an Ecosattva

To engage with the world of forms, Loy calls upon the Bodhisattva ideal, which combines an individual meditative practice and a vow to “liberate all beings.” Though based, as already noted, on the existence within us of a potential for Buddhahood, this potential has to be actualised through concrete action to help all beings. In other words, a training of the heart is being added to the training of the mind. Just as is the case for the Hindu karma yoga, serving others also allows the Bodhisattva to attain full awakening. In other words, at the same time as service to others benefits all beings, it also benefits the Bodhisattva him/herself as it allows the heart to support the mind in their quest for wisdom.

At the stage of history we are now going through, the activity of the Bodhisattva has to be focused on environmental activism, which in fact goes beyond what is currently defined as the natural environment. Both Eisenstein and Loy emphasise that the paradigm shift toward the Story of Interbeing, requires a radical transformation of our societies, which includes just about every aspect of the way they operate. It involves reforms in all aspects of our public lives – politics, finance, economy, justice, education, health care, as well as compassionate choices in our personal lives. All in all, this is a call to Buddhists to “engage” with the (impermanent) phenomena they have been trying to transcend for so long. Awakening is not a matter of transcending impermanence, it is an engagement with impermanence as interbeing.

The realisation that the world is a self-organising interconnected network of dynamic relationships, and the enacting of this interbeingness in our everyday lives, have been the aim of generations of Buddhist practitioners. While non-Buddhist systems theorists are struggling to free themselves from the story of separation mired in calculative thinking, Buddhists are uniquely placed to contribute their understanding and experience of interbeing to help them overcome the many threats now facing life on this planet.

Ultimately, as Thich Nhat Hanh writes: “If we continue abusing the Earth this way, there is no doubt that our civilization will be destroyed. This turnaround takes enlightenment, awakening. The Buddha attained individual awakening. Now we need a collective enlightenment to stop this course of destruction.”

Sources:

David Loy – Ecodharma (2018)

Charles Eisenstein – Climate – A New Story (2018)

Peter Harvey – An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practice (2013)

Francis H. Cook – Hua-yen Buddhism – The Jewel Net of Indra (1977)

Video recordings of talks and interviews by David Loy and Charles Eisenstein are available in their dedicated websites:

If you are curious about the evolution of Buddhism throughout its history, the many formulations it generated as cultural contexts changed, you may have wish to have a look at the other sections of this website.