Ch’an/Zen is most accurately described not as Buddhism reconfigured by Taoism, but as Taoism reconfigured by a Buddhism that was dismantled and discarded after the reconfiguration was complete (David Hinton).

Taoist Origins of Ch’an in Dark-Enigma Learning

David Hinton’s argument in China Root and The Way of Ch’an is that Ch’an, and consequently Zen, originated within the Taoist tradition, specifically within the school of Dark-Enigma Learning (Hsüan-hsüeh, pinyin Xuánxué), also referred to as the school of Profound Learning, which was founded by Wang Pi, and flourished during the period of the Six Dynasties (early 3rd-late 6th centuries). It was a time when Buddhism was in the process of reformulating itself in dialogue with Taoism, with which it appeared to share fundamental insights. Some of the most respected scholars/masters in both Buddhism and Taoism took part in the discussions, that, with the publication of the “Prajna Absence-Knowing Discourse” by Sheng Chao (Sangha-Fundament – 374-414) took a wrong turn, though in the end, it turned out to be a good turn. David Hinton explains that “Sangha-Fundament was well-versed in Taoist Dark-Enigma Learning, but when he read the Indian Vimalakirti Sutra he discovered insights he believed deepened the understanding of Dark-Enigma Learning. This led him to seek out Kumarajiva and become his disciple in Peace-Perpetual (Ch’ang-an), the northern capital.” As a result, “Sangha-Fundament became a key member of Kumarajiva’s translation team” and, Hinton tells us, as such, he “interpreted many of the fundamental concepts from [the Indian texts] as Dark-Enigma Learning concepts. In other words, he understood Buddhism as a different formulation of Dark-Enigma Learning. And this misunderstanding/mistranslation was crucial to the formation of Ch’an. Sangha-Fundament articulated his mongrel understanding in a number of essays, the most widely influential of which was his ‘Prajna Absence-Knowing Discourse’, written in 404. This essay was broadly recognized as a whole new approach to Buddhism, a brilliant blending of Buddhist concepts with native Chinese understanding.”

Hinton explains: “Sangha-Fundament uses a graph meaning emptiness to translate the Sanskrit sunyata. In its original Indian Buddhist context, sunyata does mean “emptiness” – but “emptiness” in the sense that things have no intrinsic nature or self-existence, that they are illusory or delusions conjured by the mind. Here, sunyata is closely associated with nirvana as a state of selfless and transcendental extinction or emptiness. This sunyata emptiness is essentially metaphysical, suggesting some kind of “ultimate reality” behind or beyond the physical world we inhabit. But that atmosphere of metaphysics is quite foreign to the Chinese sensibility and Ch’an. Indeed, there was no word in Chinese with the meaning of sunyata. The character for emptiness with its apparent similarity, was quite simply the only possibility.”

This misunderstanding was, then, an honest error in the minds of Sangha-Fundament and the numerous Chinese scholars who read his translation. Its roots lay in the huge gap between an Indian culture steeped in a quest for the eternal, and a Chinese culture happily prepared to embrace change. The eternal ground Brahmanism had sought in “being,” Buddhism had come to seek in emptiness – equating emptiness with the tranquility of nirvana. Taoists, on the other hand, were keen to align to change. So, for them, emptiness was simply the generative Absence out of which the Presence of the ten thousand things would emerge in a purely empirical sense, moved by the vital energy of ch’i. In Hinton’s words, Taoist emptiness, then, was “virtually synonymous with Absence, reality seen as a single formless and generative tissue that is the source of all things – a concept altogether different from the Buddhist sunyata. And etymologically, the ideogram’s elements are cave+labor. Hence a hollow space in earth where the work of gestation happens: emptiness as both earthly and generative.”

Hinton then concludes the section on the impact of Sangha-Fundament’s translation of the term sunyata as follows: “Thus, although the idea of enlightenment and its cultivation through meditation came from Dhyana Buddhism, the content of enlightenment was entirely Taoist. Rather than a kind of transcendental nirvana-tranquility, it is consciousness integral to the tissue of Tao’s Great Transformation. Sangha-Fundament summarizes this enlightenment in a remarkable and clearly Taoist distillation: “This heaven-and-earth Cosmos and I share the same root. The ten thousand things and I share the same original potency,” where potency is Wang Pi’s concept of an inherent nature giving shape to the emergence of things. And further anticipating Ch’an, Sangha-Fundament identifies enlightenment with meditation itself (rather than some sacred or transcendental state meditation is leading to), for he transforms meditation from the pursuit of nirvana-tranquility to Taoist understanding: “Meditation is the Way of a sage mind moving in accord with each moment,” mind identified with tzu-jan (spontaneity as occurrence-appearing-of-itself) and the unfurling of Absence into Presence.”

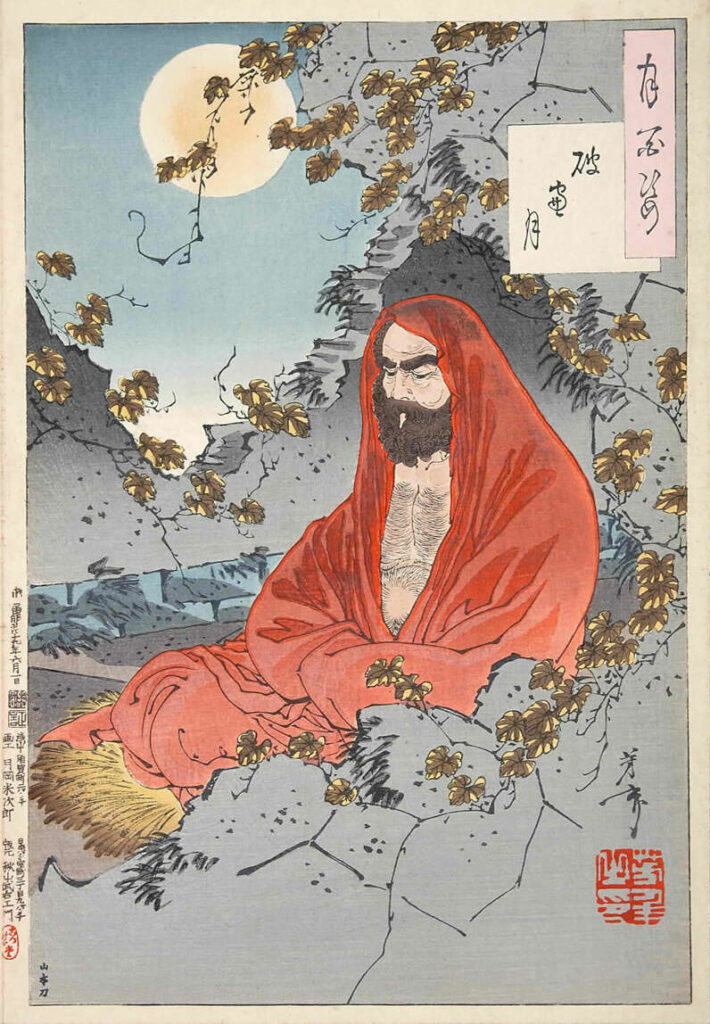

Bodhidharma (active ca 500-540)

Now, where does Bodhidharma fit in the genesis of Ch’an? In traditional Buddhist literature, Bodhidharma is credited with the founding of Ch’an.

Hinton recalls the story traditionally associated with Bodhidharma: “In the Ch’an legend, Bodhidharma was the 28th Indian patriarch in a lineage descending directly from Shakyamuni Buddha himself. He crossed the seas from India to southern China, where he encountered the emperor who ruled southern China (the country was divided into northern and southern dynasties). This emperor was a devout Buddhist, avidly studying scriptures and donating vast fortunes to support Buddhist institutions. In his earnestness, the emperor asked his exotic and sage visitor about Buddhist principles, and Bodhidharma flatly denied any value in Buddhist teachings or good works. He further denied knowing even who he himself was. Given that an emperor was revered and feared as the infallible and all powerful “son of heaven,” this was dangerously audacious behavior, and the emperor wasn’t pleased. Bodhidharma thereupon crossed the Yangtze River standing on a reed and traveled into the north. There, at Rare-Shrine Forest Monastery (Shao-lin) on Exalt-Peaks Mountain, he sat gazing at a wall in silent meditation for nine years – an echo of the legend in which Buddha attained enlightenment by sitting for seven weeks under the Bodhi tree.”

Hinton comments: “Of this legend, only the association with Rare-Shrine Forest and Exalt-Peaks seems reliable. Otherwise, there is another Bodhidharma, the one we find breathing and speaking in a group of texts gathered under his name and full of Ch’an teaching as a very deep level. Although these texts are of various and unknowable authenticity, they represent the actual Bodhidharma whose teachings had such an outsized influence within the Ch’an tradition. And they reveal a Bodhidharma quite different from the Indian patriarch of Ch’an legend.”

Hinton, of course, is not the first scholar who has revisited the question of the role of Bodhidharma as the founder of Ch’an. Bodhidharma has been regarded as, at best, a semi-legendary character. Red Pine goes as far as saying that he has met one scholar prepared to argue that he never even existed. Hinton says that “China’s artist-intellectual class, including Ch’an teachers, would have understood the Bodhidharma legend for what it is: an institutional invention meant to give the Ch’an school a pedigree proving it to be the most authentic school of Buddhism.” But he accepts that someone by that name wrote the works attributed to him. Because Hinton, as a prominent translator, is careful to include the specific images and flavours the original Chinese ideograms bring with them to characterise the technical details of Taoist philosophy and practice, instead of simply searching for traditional Buddhist terms that could more or less fit, he can see “that Bodhidharma’s teachings describe practice and awakening entirely within the Taoist cosmological/ontological framework, summarized in his routine use of key concepts like Tao/Way, Absence and Presence, tzu-jan (occurrence-appearing-of-itself), wu-wei (Absence-action), inner pattern, loom-of-origins, potency and actualization (two highly specialized concepts from Dark-Enigma Learning), etc. Indeed, “Outline of the Great Vehicle for Entering Way” long considered the most authentic of the Bodhidharma texts, begins with the two core concepts from Hsieh Ling-yün’s “Source-Ancestral Discourse”: source-ancestral and inner-pattern.” Hinton can assert that “Rather than an Indian sage newly arrived with a body of foreign wisdom, Bodhidharma operated wholly within the framework of philosophical assumptions that had been shared by Chinese artist-intellectuals for centuries.”

But, Hinton argues, “rather than advocating conventional Buddhism, [Bodhidharma] in fact consistently dismantles it: Ch’an here at its official beginning as thoroughly anti-Buddhist. This begins in the legendary encounter with the emperor, where he dismisses conventional Buddhist practices and knowledge. And it continues in Bodhidharma’s teachings, where he replaces a distant demigod Buddha with mind or original-nature as the object of Ch’an cultivation. Further, he condemns traditional practices (the six paramitas, for example) and sutra learning, describes the purpose of practice as “entering Way,” redefines karma in Taoist terms as Way unfurling one fact following inevitably after another, effectively replaces all Mahayana (Great Vehicle) teaching with his own wild and anti-Buddhist teachings when he titles his essay ‘Outline of the Great Vehicle for Entering Way’ … And it hardly stops with these examples.”

Even though the verses encapsulating the definition of Ch’an were first found in a text dating from 1108, that is, 500 years after Bodhidharma’s death, Hinton is happy to credit them to Bodhidharma:

“A separate transmission outside all teaching

and nowhere founded in eloquent scriptures,

it’s simple: pointing directly at mind

seeing original-nature, you become Buddha.”

In Hinton’s view, “Bodhidharma’s great innovation may be that he completed the reconfiguration of what was primarily a philosophical system (Taoism) into a system of spiritual practice (Ch’an). And he established the historical structure through which practice and awakening could be “transmitted” through time as a tradition.”

Sixth Patriarch Prajna-Able (Hui Neng, 638-713) and the Platform Sutra

The next step in the development of Taoist Ch’an into a Buddhist school is found in the Platform Sutra claimed by Ch’an/Zen teachers to be the foundational text of their tradition. Hui Neng is another shadowy figure in the Ch’an adventure, as one knows next to nothing about his life apart from what is said about him in the Platform Sutra, which is purported to have been written by his dharma heir, Shen Hui (whom Hinton calls “Spirit-Lightning Gather). Shen Hui is also the man Hinton credits with the “invention” of “the split between northern (gradual) and southern (sudden) schools, then argued that Prajna-Able’s southern school was the true Ch’an.” Prajna-Able is described as an illiterate peasant to illustrate two central Ch’an tenets. First, that we are all, in our original-nature, inherently enlightened. That is, we are all Buddhas. This means that awakening has nothing to do with diligent practice, for it is simply recognizing one’s originally awakened nature and must therefore be instantaneous and complete. And second, that awakening isn’t a question of learning, for deep insight is outside of knowledge and texts and teachings: Bodhidharma’s “separate transmission outside all teaching.”

Space is lacking here for the wealth of teachings found in the Platform Sutra. So I will focus on the well-known story of the poetry contest called by the Fifth Patriarch in order to identify his successor. Hinton writes: “In this story, the Fifth Patriarch asks the monks of his sangha to each demonstrate their understanding by writing a poem. Only the head monk dares venture a poem, and in it he writes that awakening comes from assiduously polishing the mind-mirror. In response, the illiterate Prajna-Able writes a poem saying there is no mirror to polish, for mind is always already awakened. This becomes a kind of historical origin-moment in Ch’an. When the Fifth Patriarch declares Prajna-Able is true heir, Prajna-Able flees the danger posed by a sangha of jealous monks. He travels to the mountain wildlands of the south and founds a Ch’an of instantaneous awakening outside of words and teachings. In stark contrast to the illiterate peasant Prajna-Able, the head monk Spirit-Lighting Flourish (Shen-Hsiu) is from the aristocratic class … The distinction between sudden and gradual was perhaps more a matter of emphasis than real difference – for both sides accepted the necessity of learning and practice as preparation for the sudden transformation of enlightenment itself. The more salient distinction perhaps between institutional orthodoxy and independent icoclasm, between cities and wild mountains, between a more conventional Buddhist approach and a more Taoist wrecking-crew approach. In any case, it is the ‘southern’ Ch’an of Prajna-Able that became the prevailing and enduring Ch’an.”

Again, because Hinton is able to see the original Chinese ideograms and keen to include the images they bring with them in his translations, he can see “Prajna-Able in the Platform Sutra operating within the Taoist cosmological/ontological framework, deploying the full panoply of Taoist concepts, even though as an unlearned illiterate he should know nothing of such things (or of Buddhist scripture, which he also seems to know well). And again as with Bodhidharma, this shows how deeply the Taoist framework functioned as the unthought assumptions shaping Ch’an thought and practice, for later teacher and students apparently saw nothing unusual in Prajna-Able slinging around these profound cosmological/ontological concepts.”

Hinton adds: “But it’s often more subtle than direct references to those foundational cosmological/ontological concepts. One good example comes in Prajna-Able’s introduction to his enlightenment. There, describing the nature of awakening, he equates understanding ch’i-weave mind with Bodhidharma’s “seeing original-nature.” This identifies the Taoist concept of ch’i-weave with the Buddhist concept of one’s own original-nature. Original-nature is of course no different from empty mirror-mind (subject of Prajna-Able’s enlightenment poem) – and so, Prajna-Able here invests consciousness with the full dimensions of Taoism’s generative cosmology: mind woven into ch’i, the Cosmos seen as a single breath-force tissue in constant transformation.”

Why it is important to recover the original version of Ch’an formulated in the terminology of the Taoist tradition

“Render therefore to Caesar the things which are Caesar’s; and to God the things that are …God’s” is, of course, part of Hinton’s intention. Ch’an can be fairly described as a blend of Taoist philosophy and Buddhist practice, and it is because Buddhism was able to provide Taoism with a set of institutional settings that Ch’an came to be identified as Buddhist. Then, when Ch’an crossed the sea to settle in Japan, teachers had to once more reformulate the teachings in a language familiar to their Japanese practitioners. If you take a close look at Dogen’s teachings, you will find that he brought back an understanding and practice that matched the Taoist interpretation – for instance shikantaza, practice-realisation, impermanence as Buddhahood, Buddha-nature inclusive of non-sentient beings, poetic use of language, being enlightened by all things, forgetting the self. And when it comes to the thinkers of the Kyoto School, it is even clearer that Ch’an/Zen, in Hinton’s words, “is most accurately described not as Buddhism reconfigured by Taoism, but as Taoism reconfigured by a Buddhism that was dismantled and discarded after the reconfiguration was complete.”And Hinton believes that Zen practitioners would benefit by learning Ch’an’s original Taoist formulation.

Source:

David Hinton – The Way of Ch’an – Essential Texts of the Original Tradition