“Scholars now generally agree that the institutional history of Chan Buddhism, or the school of Chan in a sectarian sense, began with Daoxin (580–651) and Hongren (601–674), the attributed fourth and fifth patriarchs in the orthodox lineage of Chinese Chan endorsed by later generations” (Youru Wang).

The Buddhist texts that were brought from India to China via the Silk Road in the early centuries of the common era attracted the attention of many Chinese as they presented teachings and practices that echoed their own heritage, especially that of Daoism. Translators of these texts, however, had to interpret, rather than simply translate, the teachings expressed in Sanskrit, one of the most abstract and precise languages in the world, into an idiom devoid of syntax and requiring experiential context for proper understanding. Yet over time, the Madhyamaka and Yogacara schools were established, primarily in Chinese cities. However, even in a modified form incorporating Daoist elements, the Indian schools did not survive in China, and can only be said to have influenced the three major Chinese schools that were founded there – Tiantai, Huayan, and Chan.

Tiantai school

Raud writes: “The first originally Chinese Buddhist school, Tiantai, has received its name from the Tiantai mountain in the Zhejiang province. This was the site of a temple where the actual founder – although technically the fourth head [patriarch] – of the school, Zhiyi (538-597), lived and worked … The idea of a Buddhist school came in China to be associated with the in-depth study of a particular text, and Tiantai was the school dedicated to the studies of the Lotus Sutra … However, the actual teaching of the school has only a little to do with the parables of which the sutra mostly consists. The central and radical contribution of the Tiantai school is the idea of three truths. Nagarjuna had introduced the idea of ‘two truths’ in his work, separating the conventional truth – as a sentence about something can be correct or incorrect – from the ultimate truth of emptiness of all things, and not claiming that the ultimate truth is superior or somehow more true than the conventional, or shared truth. Tiantai took this idea further and interpreted a verse of Nagarjuna to say that this equality of the two truths is itself a third one, the ‘middle’ truth. This third truth came to mean that every true proposition is true only from a certain perspective, and more than that, even a conventionally false proposition is true from some perspective in which its truth conditions are met. In other words, the truthfulness of any sentence is relational to the perspective from which it is uttered. The legacy of Zhuangzi and the debates around the ‘school of names’ are clearly a part of this assertion.”

Another of Zhiyi’s key concepts is that of “Three thousand worlds in one thought-moment.” This view, which originated in one of the fundamental teachings of the Lotus Sutra’s, could therefore be considered to be of Indian origin. But Zhiyi elaborated it into a sophisticated metaphysical edifice comprising multiple perspectives from which reality can be observed, representing up to three thousand states of mind, rather than physical modes of existence. What Zhiyi was trying to emphasise is that “each single thought-moment we might have actually contains them. The entire universe is constantly reproduced by any minute flicker of mental activity by any entity.” Rather than an inquiry into the nature of reality, motivated by the wish to “know,” as science would understand it, it is an attempt to foster an “experiential” approach to the relational nature of reality.

Huayan School

Raud writes: “During the Tang dynasty, the Tiantai school was for some time eclipsed by another Chinese innovation, the Huayan school, which was based on the study of the Avatamsaka (Flower Garland) Sutra, or Huayanjing in Chinese … It became an object of serious study only in the 7th century CE, evolving into a distinct philosophical strand of thought under Fazang (643-712), formally the third head of the Huayan school. Fazang, the son of wealthy immigrants, studied briefly with Xuanzang,” a monk famous for his seventeen-year journey to India where he studied at Nalanda University, and returned with many Sanskrit texts. But he eventually fell out with him, and became the Buddhist teacher of a powerful empress.

Huayan teachings have been described in East Asia as “the high-water mark of Buddhist philosophical effort.” In the West, little had been written on it when Francis H. Cook published Hua-Yen Buddhism, The Jewel Net of Indra in 1977. Raud summarises Huayan teachings as follows: “One of the central metaphors of the Flower Garland Sutra is ‘Indra’s net’, the image of a huge net in which all knots contain a diamond so that each of these diamonds is able to reflect every single one of the others … Huayan accepts and develops the Tiantai view of each entity being related to every other one in the universe to its logical endpoint. For this purpose, it adopts a term from classical Chinese thought, ‘principle’ (li), which it constrasts with ‘phenomenon’ (shi). The idea of ‘principle’ is first used by Han Feizi in a similar sense as the unique mode in which the Way manifests itself in each particular thing. In Huayan thought, it comes to signify an underlying reality uniting all things, more similar in its meaning to the ‘Way’ of Lao-Zhuang – possibly because ‘way’ in Buddhist discourse had been appropriated for the teaching itself, the way leading towards enlightenment. In Huayan, this underlying reality principle is understood as creative non-being, or emptiness.” The Chinese purge of Buddhism in 845 seriously harmed the school, which despite many efforts was never able to recover. The school had, however, “been exported to Korea, Japan, and Vietnam before its demise in China.” In Japan, it is known as the Kegon school, with its headquarters still at Todaiji in Nara, and its teachings have been appropriated by other Japanese schools of Buddhism. Its doctrine of “mutual identity and interpenetration of all phenomena” is often presented as an extension of the Buddha’s concept of co-dependent origination. But, under the influence of the deep connection with nature found in Daoist teachings, a new positivity towards the phenomenal world shines through the Huayan universe in which, in the words of Francis Cook, “phenomena have been not only restored to a measure of respectability, but indeed have become important, valuable, and lovely” (quoted by Jin Y. Park). Whereas in Indian Buddhism, phenomena were dismissed as “impermanence,” in East Asia, the Buddhist worldview has been described as a “phenomenalism,” with Dogen stating that “Impermanence is the Buddhahood.”

Chan School

Raud writes: “The best-known school of East Asian Buddhism is unquestionably Chan, or Zen, as it is called in Japan … It synthesized the teachings of many schools and combined them with a unique practice aimed at transcending ordinary logic in order to achieve the enlightened state of mind. Emphasizing a direct transmission from teacher to disciple, Chan officially downplayed the role of scriptures, even though it quickly developed a large body of writings of its own. The teacher-disciple relationships soon transformed into lineages of transmission, which contributed to the split of Chan into a large number of sub-schools. The main split was that between northern and southern Chan. Most later Chan lineages claim their descent from the allegedly orthodox and superior southern tradition inaugurated by Huineng (638-713), the sixth head of the school, although there is evidence that this narrative was created in retrospect by southern masters, perhaps in order to counter the imperial patronage that some masters of the northern lines had secured for themselves.”

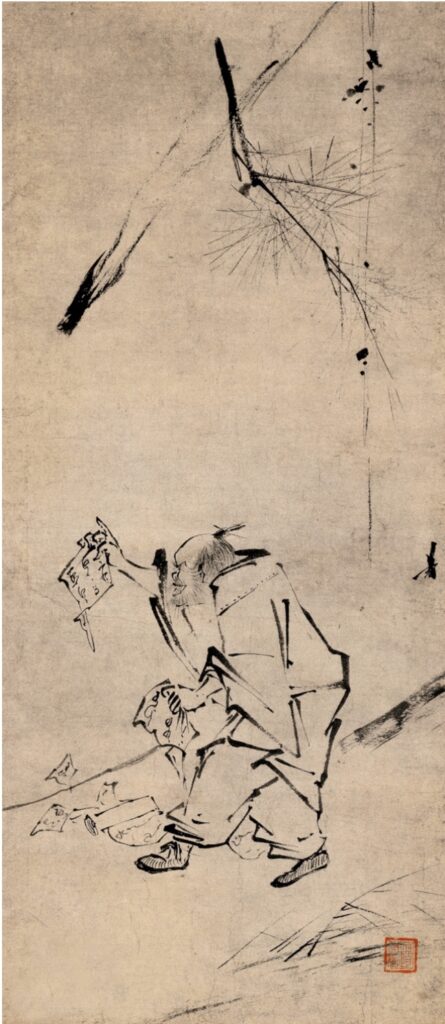

We will now turn our attention to a research article by Youru Wang entitled “Introduction: A Concise History of Chan Buddhism,” which describes in detail the rather tumultuous history of its foundation. Unlike Tiantai and Huayan, Chan did not rely on the authority of an Indian sutra as its foundational text. It, instead, advocated the rejection of all written texts. In a formula attributed to Bodhidharma, its presumed founder, but said to date from 1108, nearly six centuries after his death, Chan was defined as

“a special transmission outside the scriptures;

not established upon words and letters;

directly pointing to the human heartmind;

seeing nature and becoming a Buddha.”

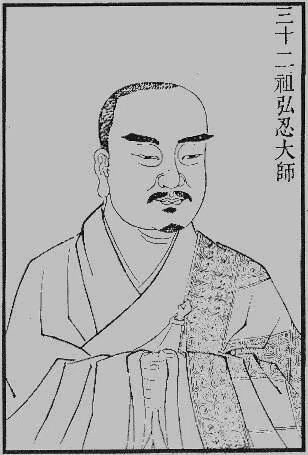

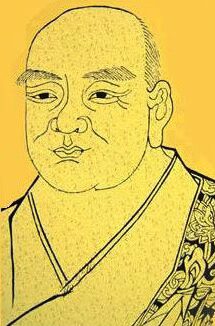

Bodhidharma has been widely regarded by scholars as a semi-legendary figure who came from India – or, in other texts – from Central Asia, during the 5th or 6th century CE. Wang, however, is more assertive when he states that, as a distinctive school, Chan did not begin with Bodhidharma, but with Daoxin (580–651) and Hongren (601–674). Wang writes: “Scholars now generally agree that the institutional history of Chan Buddhism, or the school of Chan in a sectarian sense, began with Daoxin (580–651) and Hongren (601–674), the attributed fourth and fifth patriarchs in the orthodox lineage of Chinese Chan endorsed by later generations. The status of Sengcan, as the attributed third patriarch and the dharma heir of Huike, has no known historical basis. Sengcan’s contemporary sources did not provide biographical information for him except a list of Huike’s followers, in which Sengcan’s name appeared, and a vague mention of Sengcan’s meeting with Daoxin. All details of his biography were produced in the 8th century, and the work Xinxin Ming (‘Inscription on the Faith in Mind’), attributed to him and widely used by the Chan tradition, was a forgery also from the late 8th century. However, we have much more credible information about Daoxin and Hongren from historical sources. From 624 (Daoxin’s arrival at Huangmei, in Hubei) to 674 (Hongren’s death), in only a half century, they built up the first Chan community in the history of China, kept it growing, and made Huangmei a national center for meditation training. Daoxin and Hongren had about thirty disciples (Daoxin had about a half dozen and Hongren twenty five). Among these disciples, ten were called ‘great disciples of Hongren’ by later generations. Hongren especially was a charismatic teacher and a successful leader of this first sizable Chan community.”

Hongren is, of course, the Fifth Patriarch who, in the Platform Sutra, holds a poetry contest to choose his successor. While everyone in the monastery expects Shenxiu, the head monk, to win the contest, it is Huineng, “the illiterate son of a banished official, raised in extreme poverty” (Raud) coming from the South, then a backward part of China, who, after dictating his poem to a monk, is chosen as the Sixth Patriarch. Huineng is said to have attained enlightenment when overhearing a verse from the Diamond Sutra. Hongren asks Huineng for a secret meeting during which he gives him the bowl and robe symbolizing his accession to the status of patriarch, but at the same time orders him to leave the monastery immediately, and remain in hiding for some time.

All this is very strange indeed. But there is more to come. Tradition says that the text of the Platform Sutra was compiled by Fahai, a direct disciple of Huineng, shortly after his death. According to modern scholarship, however, the text was reworked over several decades, with contributions by the Oxhead school and Shenhui (684-758), described as a monk who “claimed” to be a direct disciple of Huineng, and who was eager to promote his teacher against Shenxiu. Shenhui, however, did a lot more than rework Huineng’s teachings, and recount the rather dubious circumstances of his accession to patriarchship.

Wang writes: “Around 732, about two decades after Huineng’s death, Shenhui, one of Huineng’s disciples, came to the north to wage a public criticism on Shenxiu and the Northern school. In his sermons and the many debates he participated in, especially the famous debate at Huatai with the master Chongyuan (d.u.), an influential figure of the Northern school, Shenhui subverted the Northern school’s establishment of Shenxiu as the sixth patriarch of Chan, and declared the supremacy of the Southern school and the legitimacy of Huineng as the true sixth patriarch. Shenhui provided one of the justifications for this assertion in a dramatic and unprecedented fashion by inventing the story of the transmission of Bodhidharma’s robe from Hongren to Huineng.”

Wang continues: “Moreover, in terms of his radical non-dualism, Shenhui criticized Shenxiu and the Northern school’s dualistic formulation of pure and defiled aspects of the mind and its approach to meditation practice as promoting ‘gradual enlightenment’ (jianwu) and ‘gradual cultivation’ (jianxiu) in contrast to the Southern school’s ‘sudden enlightenment’ (dunwu) and ‘sudden cultivation’ (dunxiu). Though he gradually increased his influence and developed his relationship with the elites, Shenhui’s campaign was not successful until he became instrumental in the Tang government’s fund-raising, by selling certificates of ordination to aid the military crackdown on the An Lushan rebellion. The emperor Suzong (r. 756–762) awarded him imperial patronage and a special building at Heze Temple. It seems not an overestimation that Shenhui’s campaign to some extent changed the course of Chan Buddhism, although this change – Huineng and the Southern school replacing Shenxiu and the Northern school – had underlying social-historical conditions. However, Shenhui and his followers did not achieve the ultimate benefit from their campaign. It is true that Shenhui’s legacy – his uncompromisingly non-dualistic and apophatic rhetoric; his claim of the orthodoxy of Huineng, the Southern school, and the sudden teaching (dunjiao); and so forth – was well carried on by the later generations of Chan, but his lineage was quickly marginalized and did not last long. Even during his lifetime, Shenhui had to concede that some kind of gradual cultivation after initial awakening must be allowed. His later follower Zongmi (780–841) had to make clear that sudden enlightenment needed to be followed by gradual cultivation. The pseudo problem of sudden versus gradual soon faded away from the center stage of the internal debate of Chan.”

Bodhidharma, Daoxin, Hongren, Huineng … or Shenhui?

Seventh Patriarch of the Chan School

Based on historical evidence, we are left with five potential founders of the Chan school. Bodhidharma, the official founder held by the tradition, may not have existed, but if he did, he was not a master from South India who brought a fully formed Chan school to China. Daoxin and Hongren would be better candidates because they were instrumental in initiating the process that led to the creation of Chan. Shenhui, who fought for decades to have the new school recognised by the powers of the day, could be considered the institutional founder of the school. He was eventually confirmed as its Seventh Patriarch.

Historically, insofar as the purported teachings of Huineng in the Platform Sutra have laid out the foundations for the Chan/Zen lineage, he has to be regarded as its spiritual founder. The irony is that we know next to nothing about his life besides what Fahai and Shenhui tell us in the Platform Sutra.

In the comments on his translation of the Platform Sutra, Red Pine writes that, according to the tradition, “one day, as he was delivering firewood to a shopkeeper, [Huineng] heard a customer recite the Diamond Sutra. ‘Where did you get this scripture you’re reciting?’ asked Huineng. The man had learned it from the monks at Master Hongren’s monastery, and been told that ‘just by memorizing the Diamond Sutra they would see their natures and immediately become buddhas’. ‘As soon as I heard the words’, Huineng recalled, ‘my mind felt clear and awake’. Huineng immediately set off for the monastery.”

Red Pine adds that this spontaneous understanding could be interpreted as an indication that Huineng, though poor and illiterate, was actually a bodhisattva getting near the end of his training. Others have seen his illiteracy as a metaphor for a mind that was closer to enlightenment because it was free from the conceptual layers which education heaps on top of our pure original mind.

Huineng’s first meeting with Master Hongren was not encouraging. Upon hearing that he had come from the South, he called Huineng a “jungle rat” to which an unfazed Huineng replied, ‘People come from the north or south, not their buddha nature. The lives of this jungle rat and the Master’s aren’t the same, but how can our buddha nature differ?’ This of course gave Hongren the opportunity to highlight the central teaching of the Platform Sutra, which is precisely that of buddha nature. Huineng was then sent to the milling room, where he “pedaled a millstone for more than eight months.”

There is undoubtedly a reason why an illiterate man from a rough part of China was chosen as the author of the foundational teachings of this particular new school. Chan practitioners were very critical of the scholastic schools based on the study of Indian Mahayana sutras that had become established in large Chinese cities. Huineng was a man who had gained enlightenment without having read these sutras. He was able to do so because, as he confirmed in his reply to Hongren, he, like every human being, was endowed with buddha nature. Just overhearing a verse from the Diamond Sutra had “actualised” his dormant buddha nature. As neatly encapsulated in the formula attributed to Bodhidharma, Chan’s mission was to establish “a special transmission outside the scriptures; not established upon words and letters.”

The above, then, is the result of the research by two of the many scholars involved in the on-going research on the origins of the Chan/Zen tradition and the extent of its connection with Daoism. Inasmuch as Buddhist practitioners may feel uneasy when reading such scholarly material, we should keep in mind that, what called for a creative reform of Buddhism in China was the need to adapt its teachings to the cultural mentality of a population that found it difficult to resonate with the abstract formulation of the Indian sutras, because Chinese had been used to relate experientially with the intimations of the Dao.

As Harold Roth shows in The Contemplative Foundations of Classical Daoism, contemplative meditation had been practiced in China as early as 330 BCE, and both the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi reflected insights gained through this practice. Chinese Buddhist teachers could draw on already existing Daoist practice to complement their teachings with the direct experience that meditation provided. Hence the emphasis on the rejection of “words and letters” and the emphasis on “one’s pointing directly to one’s mind to see one’s own true nature.” “Samadhi,” in the sense of concentration, had been taught by Sakyamuni Buddha, but it was only one of the eight points of the Noble Eightfold Path, and as a religious practice based on the worship of Dhyani Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, Mahayana Buddhism had turned into a primarily devotional practice. Practice for monastics consisted in the repetition of sutras they had learned by heart, not in the contemplation of their “original mind.” Early Daoist practitioners, on the other hand, had already learned how to “become one with Dao.” In the words of Yan Hui, in the Zhuangzi, quoted by Roth: “I let organs and members drop away, dismiss eyesight and hearing, part from the body and expel knowledge, and merge with the Great Pervader. This is what I mean by ‘just sit and forget’.” (6/92-3; translation by C T Graham).

Sources:

Rein Raud – Asian Worldviews (2021)

Francis H. Cook – Hua-Yen Buddhism, The Jewel Net of Indra (1994)

Jin Y Park – Zen, Huayan, and the Possibility of Buddhist Postmodern Ethics (2008)

Red Pine (Bill Porter) – The Platform Sutra: The Zen Teaching of Huineng (translation and comments – 2008)

Youru Wang – “Introduction: A Concise History of Chan Buddhism” research paper (2017)

Harold D Roth – The Contemplative Foundations of Classical Daoism (2021)