“The wide range of meaning links our human mind (intention/thought) to the originary movements of the Cosmos … opens the cosmological context for the idea of an “intelligence” that infuses all existence, and of which human thought and emotion share with wild landscape and, indeed, the entire Cosmos, a reflection of the Chinese assumption that the entire human and non-human form a single tissue that “thinks” and “wants.” (David Hinton)

Even before being told that the word Ch’an, which the Japanese pronounce Zen, was originally a transliteration of the Sanskrit word dhyana, meaning meditation, most people know that the primary practice of that school is a contemplative practice, and are not surprised when being taught a particular seated technique of “meditation” before attending their first “dharma talk.” Besides an emphasis on the correct sitting position, the emphasis will be on what to do – or not do – with one’s mind during the next half hour. The focus is definitely on the mind soon to be taken over by thoughts if one does not pay attention. If breath is mentioned, it is to say that counting one’s breaths helps with concentration. I doubt that a modern Zen teacher would say that “meditation begins with the breath.” But, at least in East Asia, the breath has not lost its association with the vital energy known as “ch’i.”

Meditation begins with the breath

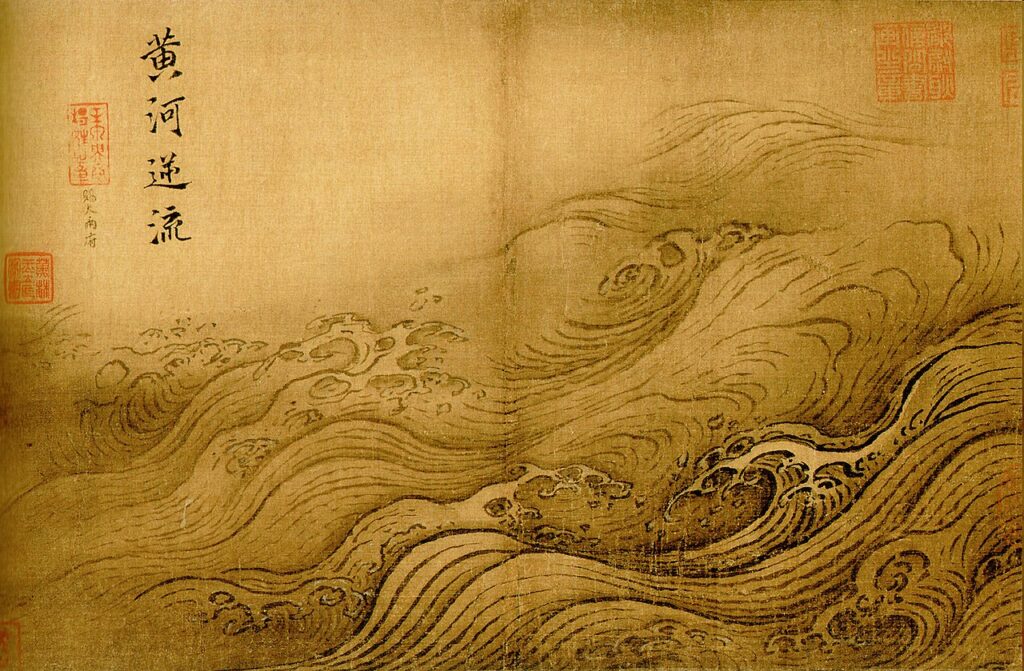

Hinton writes: “Meditation is the heart of Ch’an practice, and meditation begins with the breath: sitting with the breath, attending to the breath. Breath helps settle thought and quiet mind. But in Ch’an, breath is much more. Life in, life out: breath reveals the entire conceptual framework that shapes Ch’an. Each breath arises from nothing and vanishes back into nothing, the essential movement of Tao: inhale and exhale, sound and silence, full and empty, life and death. Breath moves always at that generative origin-moment/place. And so, attending to breath, like attending to thought, reveals how utterly we belong to that cosmological/ontological process of Tao.”

An early focus on the breath is also found in the West, with the Greek “pneuma,” originally meaning “breath” that came to refer to “spirit” or “soul” in a religious context, and psyche, also translated as spirit or soul, said to mean “breath of life.” So it appears that in both East and West an early connection between breath and mind was seen that has now been forgotten in both Buddhism and Christianity.

Chinese ideograms for breath

Taoist Ch’an was able to keep it alive through representing it in the ideograms used for “breath” in the Chinese language as well as embodying it in self-cultivation practices. Hinton tells us that there are, in Chinese, two ideograms for “breath,” “each in a quite different way, though they are often combined for richer expressiveness. In an early form, the top element appears to render a kind of emergence out of a generative space (generative emergence a reasonable assumption because it is the fundamental structure of things in Taoist thought). And in its ancient oracle-bone form, that emergence appears to come from two side-by-side spaces that must represent lungs, and through an opening that must be a mouth. Artistically, it’s a beautiful image … which becomes an equally beautiful concept: ‘breath-emergent’. The other word for breath is more expansive in its implications: (ch’i), which describes the Cosmos as a single generative tissue breathing through its perpetual transformations. It seems that this graph was originally a veritable picture of sky’s dynamic forces, which are driven by the sun heat. Although the ancient oracle-bone forms are unknown, other early forms of [this sign] suggest the graph originally contained the image of vapor rising under the influence of heat. This heat appears as sun (portrayed in oracle-bone script) or as flame … Hence, ch’i in its most quintessential visible form: sky-ch’i, that living emptiness that we breath in and out.”

Role of imagination in the genesis of mind

When it comes to mind, words describing mental states and processes “originally referred to images from the observable universe … The human mind slowly created itself from those images through a complex process of metaphoric transference, thereby weaving the structures of identity from the empirical Cosmos. Our Western concepts such as spirit or psyche find their etymological origins in wind and breath, essentially returns us to those primal levels of consciousness where the sense of consciousness or mind was being formed, for at those depths there is no distinction between breath and mind. At these originary metaphoric levels where consciousness shaped itself, the unity of mind and breath becomes apparent, and attending to breath returns us to that place. This suggests a deeper dimension to the connection between breath and mind, for breath is that very sky taken inside us physically, while empty consciousness is that sky taken us mentally.”

This process of metaphoric transference has been recently brought to light by a number of philosophers and scholars who have turned to an investigation of imagination as the way the ten thousand things have emerged out of apparent nothingness. Buddhism and Christianity have similarly blamed “concepts” seen as the activity of ‘taking to oneself” the many things we perceive around us, which led them to prescribe a control of desires. Imagination now appears as an activity that does not seek to grab, and instead inspires us to act in an intuitive and loving way. Children use it all the time, and fairy tales have been relying on it to appeal to their remarkable imaginative skills. In Western philosophy it has been studied by Kant and Heidegger, among others, and I found it to have attracted the interest of Miki Kiyoshi, a philosopher of the Kyoto School and the author of The Logic of Imagination. In general terms, however, imagination has been treated as a Cinderella by intellectuals because of its association with mythology. Seeing imagination as the principle at work in the genesis of the mind in Taoism is worthy of note.

Primal unity of breath-emergence and mind

Hinton continues his study of the two ideograms for breath. “The bottom half of the second graph for breath suggests that primal unity of breath-emergence and mind. This is doubly interesting because [the upper part of it] itself in fact means “self” (not surprising as it is breath that gives life), so the whole graph associates breath and self/mind. The mysterious unity of breath and mind becomes immediately apparent in ch’i, for if we could trace consciousness back to its origins in the primeval word-hoard, back beyond the metaphoric constructions of subjectivity with its intentionality and reason, all the way back to some primal self-awareness of the opening of consciousness with its life and movement, we would no doubt find its empirical origin in the emptiness of dynamic living sky with its everchanging breezes and humidity, temperature and weather and bottomless blue distances. And that leads us back to the cosmological dimensions of the Ch’an (“meditation”) graph, showing three streams of light emanating earthward from the three types of heavenly bodies seen as bright distillations, or embryonic origins, of ch’i. How remarkable that those vast cosmological dimensions open so intimately in meditative breath-emergent mind!

Mind is not a transcendental entity in Daoism

In its common sense, the word “mind” to refer to as “the center of language and thought and memory, the mental apparatus of identity. But in Ch’an/Zen and Buddhism in general it “refers most often to consciousness emptied of all contents.” Contemporary philosophers tend to use the word “consciousness” instead of “mind,” as it is easier for Westerners to visualise their consciousness as empty.

In addition to this double meaning of “mind,” Hinton points out, mind as we understand it in the modern West is fundamentally different from the understanding of mind in a Taoist/Ch’an framework. Hinton explains: “There was no sense in that framework of mind as a transcendental entity such as the West’s “spirit” or “soul” that is ontologically separate from the world around it. Chinese has words that translate as “spirit” or “soul,” but “spirit” was considered a particular condensation of ch’i breath-energy, and was therefore comprised of ch’i’s two aspects: the yin spirit, which dispersed into the earth at death, and the yang spirit, which dispersed into the heavens at death. In either case, they were more like energy fields that dissolve away soon after death.”

In addition the graph for “heart” – hsin – also means “mind”, and is therefore often translated as “heartmind.” Hinton describes it as “a stylized version of an earlier graph, which is an image of the heart muscle, with its chambers at the locus of veins and arteries.” Chuang-Tzu’s text on the “Fasting of the Heart” is also referred to as the “Fasting of the Mind,” and Hinton insists that what Buddhism calls the Heart Sutra should be called the Mind Sutra. The reason is that Chinese and Japanese people tend to locate thought as arising from their very “core,” which is the heart. I read that if you ask a Japanese person to point to their mind, they instinctively point to their heart. There is then an “integration of the mental and emotional realms” that is a far cry from the sharp distinction between thinking and feeling that is made in Western cultures.

Hinton adds that “an even more dramatic expansion of our conventional sense of identity-center mind is distilled in the root concept “i.” “Containing the pictographic element for “(heart)mind” [the graph for the root concept] has a range of meanings: “intentionality,” “desire,” “meaning,” “insight,” “thought,” “intelligence,” “mind,” (the faculty of thought). The natural Western assumption would be that these meanings refer uniquely to human consciousness, but [the graph for the root concept] is also often used philosophically in describing the nonhuman world, as the “intentionality/desire/intelligence” that shapes the ongoing cosmological process of change and transformation. Each particular things, at its very origin, has its own (root concept), as does the Cosmos as a whole. [The root concept] can therefore be described as the “intentionality/intelligence/desire” infusing Tao/Absence and shaping its burgeoning forth into Presence, the ten thousand things of this Cosmos. It could also be described as the ‘intentionality,” the inherent ordering capacity, shaping the creative force of ch’i.” Japanese primatologist, ecologist, and anthropologist Imanishi Kinji used a similar concept to critique Darwin’s theory of evolution primarily based on random mutations and competitive selection to produce what is referred to in translation a “theory of evolution presupposing ‘subjectivity’” in which all species consciously strive to “fit in” with other species. Would “intentionality” be a closer translation?”

“Mind as woven wholly into the ever-generative ch’i-tissue, into a living and “intelligent Cosmos”

Hinton concludes the subsection on mind as follows: “This wide range of meaning links our human mind (intention/thought) to the originary movements of the Cosmos … opens the cosmological context for the idea of an “intelligence” that infuses all existence, and of which human thought and emotion share with wild landscape and, indeed, the entire Cosmos, a reflection of the Chinese assumption that the entire human and non-human form a single tissue that “thinks” and “wants.” Daoist China could not have given birth to a Descartes, who sharply distinguishes res cogitans – the mind – and rex extensa – meaning matter, but also emotions and feelings, with mind asserted as “a more or less transcendental identity-center separate from and looking out on reality.“ It instead emphasises the inseparability of a mind as “woven wholly into the ever-generative ch’i-tissue, into a living and “intelligent” Cosmos.” Just as heart and mind are united into “heartmind,” breath and mind are united as “ch’i-thought” or “ch’i-mind.” Isn’t it what biological science today refers to as the self-organisation of the universe? Were it not interwoven with mind/intelligence, matter would not be able to self-organise.

Source:

David Hinton – China Root – Taoism, Ch’an, and Original Zen