David Hinton regards Hsieh Ling-yün as having achieved “the foundational shift in awareness that is crucial to Ch’an awakening as “seeing original-nature”: the experience of oneself not as a center of identity inside its envelope of thought and memory, but as an empty mirror, the contents of which is wholly the world it faces. And more: ‘original-nature’ as nothing less than Tao or Absence, the generative existence-tissue that is the wordless Cosmos whole.”

Ch’an as a focus on a new form of meditation

In the context of Buddhism, Ch’an, and consequently, Zen, which is simply the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese ideogram for Ch’an, is said to be a transliteration of the Sanskrit word dhyana, a term that had come to refer to “meditation” as such. “The term was adopted as a name,” David Hinton points out, “because Ch’an focuses so resolutely on meditation practice as the primary path to awakening.” It was the practice which, in the famous description of Zen attributed to Bodhidharma, one would use to “point directly to [one’s] mind in order to “see into [one’s own true] nature and [thus] attain Buddhahood.”

Does this mean that Ch’an as the emphasis on “meditation practice as the primary path to awakening” had been a decisive contribution of Indian Mahayana to the birth of Ch’an itself? Yes and no. Ch’an/Zen did heavily focus on seated meditation, and this came from India. Early Daoist sages are rarely depicted seated in the lotus position. But the particularly form of zazen Dogen’s master Rujing practiced – Silent Illumination” which Dogen adopted as shikantaza – “just sitting” – is very different from Indian jnana, samatha or vipassana, so much so that some Zen teachers hesitate at calling it “meditation”! Likewise the use of koans was unknown in India, and therefore constitutes a Chinese contribution to Ch’an.

Dark-Enigma Learning (3rd century CE)

As a school, Ch’an can be regarded as the outcome of an encounter between Buddhism and Taoism in the context of the Dark-Enigma Learning movement – traditionally called the Profound Learning School – that developed in the 3rd century CE.

Hinton writes: “The philosophical Taoism of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu was reenergized eight centuries after its origins by a philosophical movement known as Dark-Enigma Learning, which arose in the 3rd century CE. Its two major figures, Wang Pi (226-249) and Kuo Hsiang (252-312), articulated their thought in the form of commentaries on the seminal Taoist classics: I Ching, Tao Te Ching, Chuang Tzu. In these commentaries, they emphasized and deepened the ontological and cosmological dimensions of those seminal texts, and it was those dimensions that blended with newly imported Buddhism to create Ch’an. Or perhaps more accurately: newly imported Buddhism gave the Taoism of Dark-Enigma Learning an institutional setting and a form of actual practice.”

What about Bodhidharma, then? Hinton explains: “In the official Ch’an legend, Bodhidharma brought Ch’an from India more or less fully formed around 500 CE, but his teaching is clearly built from the traditional Taoist conceptual framework, a fact revealed most simply in the way he depends on terms and concepts central to that Taoist system.” Red Pine, who translated four writings attributed to him, admits that he has met at least one scholar prepared to accept that Bodhidharma never existed. Most scholars have settled for a characterisation of Bodhidharma as a “semi-legendary” figure. He is said to have been the third son of a Pallava king, and to have been taught by Prajnatara, a Buddhist master from Magadha, the birthplace of the Buddha, at the time part of the Gupta empire. Though Bodhidharma’s master was first assumed to be male, Dogen refers to Prajnatara as female in chapter 50 of the Shōbōgenzo. Nothing, however, is known of a characteristically Zen Buddhist school in the Pallava kingdom, and to complicate matters, other texts claim that Bodhidharma came from Central Asia.

Hinton continues: “In fact, Ch’an’s origins are found a century or two earlier when Buddhist artist-intellectuals began melding Buddhism and Dark-Enigma Learning, which was broadly influential among artist-intellectuals at the time. In this process, they gave first form to most of the foundational elements of Ch’an that we will encounter in the following chapters. First among these, perhaps, is meditation.

Chinese pictograph used for Ch’an turns it into deeply meaningful Taoist representation

Hinton explains that dhyana was first transliterated as Ch’an-na, but the second graph for “na” was soon dropped leaving only the graph for Ch’an. And he describes this graph as composed of two elements with the element on the right “showing heaven as the line above, with three streams of light emanating earthward from the three types of heavenly bodies: sun, moon, and stars. These three sources of light were considered bright distillations, or embryonic origins, of ch’i, the breath-force that pulses through the Cosmos as both matter and energy simultaneously – the dynamic interraction of its two dimensions, yin and yang, giving form and life to the ten thousand things and driving their perpetual transformations.” Such a representation is strangely reminiscent of the modern scientific theory wherein “stars are in fact the “embryonic origins” of reality. For in their explosive deaths, stars create the chemical composition of matter. And in their blazing life, they provide the energy that drives earth’s web of life-processes.”

Ch’an meditation as “seeing original-nature” was infused with cosmological dimensions

It is, then, in the context of the Dark-Enigma Learning school that Ch’an meditation evolved as “a primary method of awakening understood as ‘seeing original-nature’ … The common meaning of ‘Ch’an’ was simply ‘altar’ suggesting a spiritual space in which one can be in the presence of celestial ch’i-sources.” As such, “it was infused with cosmological dimensions” and was also “a practice of scientific observation, close empirical attention to the nature of consciousness (‘seeing original-nature’) and its movements.”

The Indian “dhyana” involved “fixing the mind upon emptiness and tranquility.” This method was also known in ancient China, as it appears in this passage of Chuang Tzu. “Gaze into that cloistered calm, that chamber of emptiness where light is born. To rest in stillness is great good fortune. If we don’t rest there, we keep racing around even when we’re sitting quietly. Follow sight and sound deep inside, and keep the knowing mind outside.”

But, Hinton adds, “Here at this stage in Ch’an meditation … we have moved beyond dhyana’s nirvana-tranquility and deep among Ch’an’s cosmological and ontological roots in Taoism, inhabiting a generative origin-moment/place in the form of “that chamber of emptiness where light is born.”

In Ch’an meditation, as we attend to “the rise and fall of breath,” we watch “thoughts similarly appear and disappear in a field of silent emptiness. From this attention to thought’s movement comes meditation’s first revelation: that we are not, as a matter of observable fact, our thoughts and memories. That is, we are not that center of identity we assume ourselves to be in our day-to-day lives, that identity-center defining us as fundamentally separate from the empirical Cosmos. Instead, we are an empty awareness that can watch identity rehearsing itself in thoughts and memories relentlessly coming and going. Suddenly, and in a radical way, Ch’an’s demolition of concepts and assumptions has begun. And it continues as meditation practice deepens.”

It is no longer a matter of cultivating “consciousness as a selfless and empty state of ‘non-dualist’ tranquility.” Instead the goal is to watch thoughts, let them come and let them go, as a means of undermining the identity-centre that separates us from the cosmos. Hinton writes: “In Ch’an, the process of thoughts appearing and disappearing manifests Taoism’s generative cosmology, reveals it there within the mind. And with this comes the realization that the cosmology of Absence and Presence defines consciousness too, where thoughts are forms of Presence emerging from and vanishing back into Absence, exactly as the ten thousand things of the empirical world do. That is, consciousness is part of the same cosmological tissue as the empirical world, with thoughts emerging from the same generative emptiness as the ten thousand things.”

Again, this is suggested by the ideograph for monastery which represents “a hand below (showing a wrist with fingers and thumb) touching a seedling above (stem and branches growing up from the ground). This seedling image suggests ‘earth’ as the generative source, so the graph’s full etymological meaning becomes something like ‘earth-altar’, a spiritual place where one ‘touches the generative’.”

When the stream of thoughts falls silent “we inhabit the most fundamental nature of consciousness, known in Ch’an parlance as empty-mind or original-mind being” represented by the image of a tree (with earlier forms showing a trunk with branches spreading above and roots below). This appears to be the tranquil emptiness of dhyana meditation, an emptiness in which mind is a mirror reflecting through perception the world with perfect clarity. But Ch’an meditation reveals that original-mind/mirror to be nothing other than Absence, generative source of both thought and the ten thousand things, for it is also the source from thoughts emerge.” It is … something like ‘original source-tissue’: hence, “original source-tissue mind.” As far as I know, this synchronisation between the breath and the coming and going of thoughts during meditation, leading to one’s identification with the generative source of both thoughts and the ten thousand things, is a dimension that has been lost in the practice of Zen in both Japan and the West.

“Regarding The Source Ancestral”

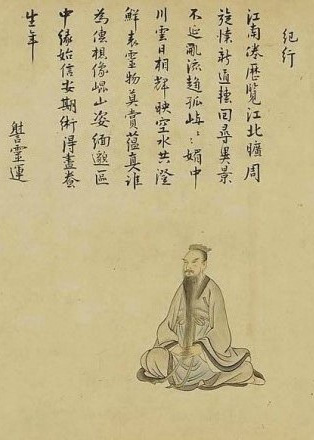

In addition to Seng Chao and Tao Sheng, Hinton indicates that the most influential Buddhist intellectual involved in the integration of dhyana Buddhism and Dark-Enigma Learning was “Hsieh Ling-yün (385-433), a giant in the poetic tradition who was a very serious proto-Ch’an practitioner. Hsieh wrote a short essay entitled ‘Regarding the Source Ancestral’, where “he dismisses the traditional Buddhist doctrine of gradual enlightenment because ‘the tranquil mirror, all mystery and shadow, cannot include partial stages’. And from this comes a description of meditation’s fundamental outline that takes a decidedly Taoist form: “become Absence and mirror the whole.” Hinton regards Hsieh as having achieved “the foundational shift in awareness that is crucial to Ch’an awakening as “seeing original-nature”: the experience of oneself not as a center of identity inside its envelope of thought and memory, but as an empty mirror, the contents of which is wholly the world it faces. And more: ‘original-nature’ as nothing less than Tao or Absence, the generative existence-tissue that is the wordless Cosmos whole.” And this took place three centuries before Huineng, the illiterate “barbarian from the South,” became the Sixth Patriarch, thereby insuring the success of the Southern School of sudden enlightenment, representing the Taoist practice of Ch’an, by defeating Shen-hsiu in a poetry contest, as narrated in the Platform Sutra.

Source:

David Hinton – China Root – Taoism, Ch’an, and Original Zen

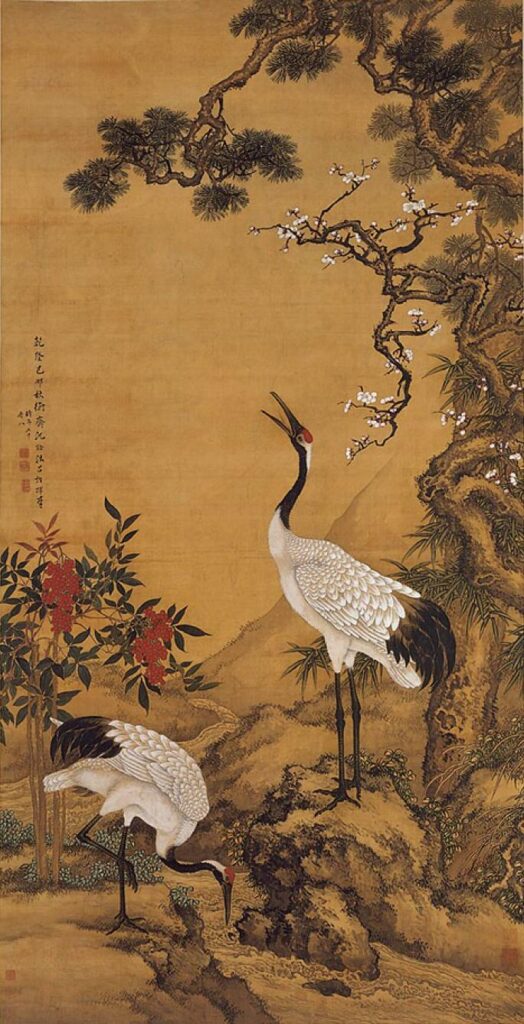

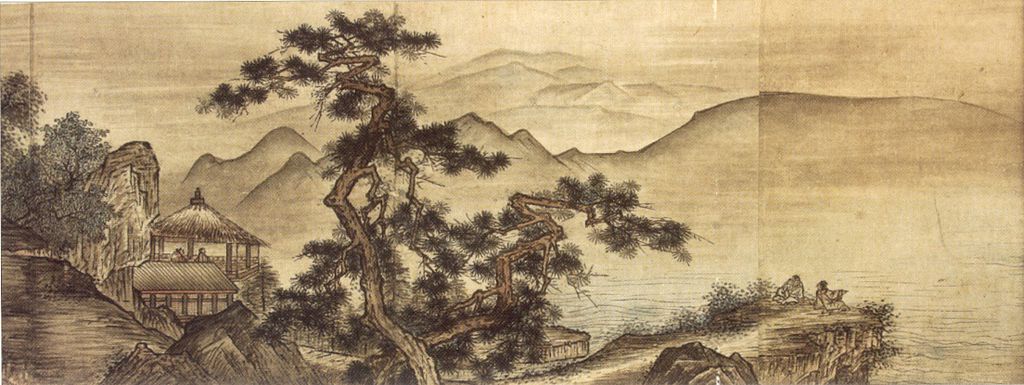

– Honolulu Museum of Art