No-self as true subjectivity

Anatman as a response to the Upanisadic teachings about atman

One of the core teachings of the Buddha is that of anatman, usually translated as “no-abiding self,” or simply “no-self.” As an explicit rejection of the Upanisadic teaching concerning the atman, the use of the word anatman did signal that the Buddha was stepping out of the Brahmanical fold. This is the reason why Buddhism has been classified as a heterodox teaching. To be sure, it also set Buddhism apart from most religious creeds, where some form of belief in a soul-like entity is one without which they would not make sense, even if the definition of what this “soul” is can differ widely.

As the Buddha’s response to the teachings of the Upanisads, especially those of Yajnavalkya in the Brhadaranyaka Upanisad, anatman was originally a mere denial of the existence of atman, “the soul as defined in the Upanisads.” Crucially, it should not be misunderstood as the negation of the existence of “subjectivity” as a function or a process.

In How Buddhism Began Richard F. Gombrich writes that “in the Upanisads … atman, is opposed to both the body and the mind; for example, it cannot exercise such mental functions as memory and volition. It is an essence, and by definition an essence does not change. Further, the essence of the individual living being was claimed to be literally the same as the essence of the universe.”

In other words, atman refers to the metaphysical relationship between the “small self” and the Cosmic Self (or God). It presents the Cosmic Self as present in each human being who, through it, “participates in the divine.” It is the divine within, and as such it is an “essence” which does not change, since the divine is, by definition, what is permanent beyond the illusory realm of changing phenomena. This view derives from a very ancient view of the universe, having perhaps originated in Mesopotamia, which can be encapsulated in the well-known formula “as “as above, so below.” “The microcosm (man) mirrors the macrocosm (the universe). Both have an essence, a true nature, a ‘self’ (atman), which is the same for both. So at the cosmic level brahman and atman are to be understood as synonyms.” (Gombrich)

This, then, was the view the Buddha rejected. “He was refusing to accept that a person had an unchanging essence,” adding that “it was something very few westerners have ever believed in and most have never even heard of.” (Gombrich)

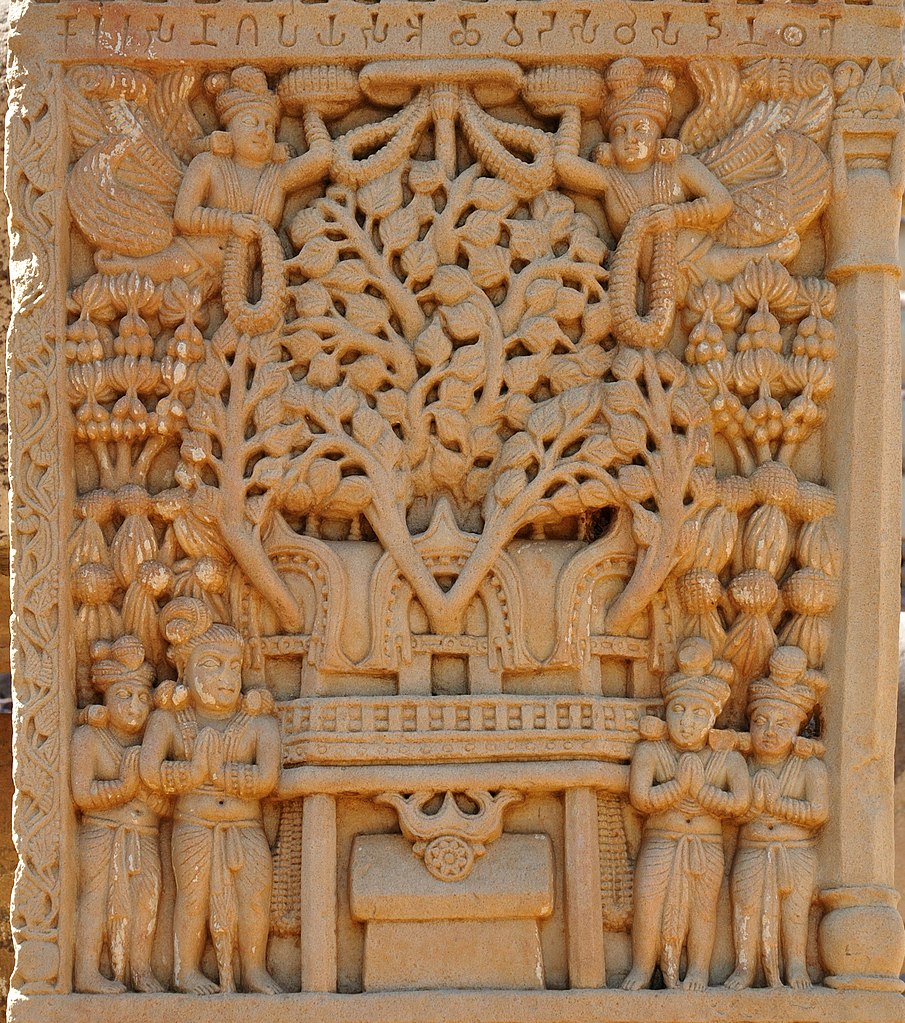

Pre-Vedic renunciates challenge the substantial views of the mainstream Vedic wordly creed

The original religion that the Indo-Aryans had brought with them when they entered Northern India around 1700 BCE had been what Govind Chandra Pande, calls a “creed of worldliness” (pravrtti-dharma), hardly a “religion” as we define it today. Lavish sacrifices and elaborate rituals were offered to the tribal gods to secure their benevolent protection, as well as success on the battlefield, and pretty much in whatever these people happened to undertake, wealth, political power, territorial expansion, etc.

It is only in the centuries preceding the time of the Buddha that this pre-ethical religion had been challenged by “creeds of renunciation” (nivrtti-dharma) developed by the sramanic schools. “In the Upanisads,” says Pande, “the doctrine of ritual act is often replaced by that of knowledge … and at the same time the moral rather than the ritual component of action tends to be emphasized.” Pande adds that, only then did “Vedic religion advance from pursuing the world to transcending the world.”

The linguistic idiom available to the authors of the Upanisads had shaped Indo-Aryan thought into what Hegel described as “intellectual substantiality.” Echoing Hegel, Nakamura Hajime states that “as a result of the Indian propensity for the abstract notion, in their way of thinking an abstract idea is expressed as if it were a concrete object, ie, in their thinking process the universal is easily endowed with substantiality.”

Those who, like the yogis and Daoist sages, sought self-transformation, nurtured empathetic intuition so as to flow with the world. For them, “to know” was a process of embodiment, a coalescence with all “things.” As the Daoists brilliantly put it, the mind is located in the heart, and is properly called a “heart-mind.” Those who, like the Brahmins and the Greeks, sought to acquire and control the world, have been more inclined to see it in substantial terms, things endowed with being, and as solid entities supported by an ultimate reality that is permanent.

The “ethical turn”

The “ethical turn” from the early Vedas to the Upanisads, some time around the 7th century BCE, that is, not long before the time of the Buddha, coincided with the elaboration of the doctrine of reincarnation as well as the decision by many Brahmins to join the sramanas. According to the newly adopted principle of the Four Stages of Life, older Brahmins who had fulfilled their family and social duties, were encouraged to spend the last years of their lives as renunciates. These Brahmins learned to master meditation and yogic practices, seeking release in a disidentification from the individual self to merge in the Cosmic Self. Escape from the cycle of rebirths, Gombrich explains, was “by gnosis of a hidden truth, brahman, which is the esoteric meaning of the sacred texts (the Vedas). That truth is to be realised = understood during life, and this will lead to its being realised = made real at death. He who understands brahman will become brahman. In a less sophisticated form of the doctrine, brahman is personified, and the gnostic at death joins Brahman somewhere above the highest heaven.”

For the authors of the Upanisads, the existence of an atman within each human offered a convenient entity which could be passed on from life to life according to karma, the enforcement of good behaviour being one of the pillars of political rule. The Buddha’s rejection of the existence of such an entity gave headaches to early Buddhist philosophers, often at a loss to explain how karma was passed on in the absence of a substantial entity operating as a vehicle.

No-self is true subjectivity

When elucidating the meaning of anatman, scholars are quick to move on to the theory of the skandhas (bundles of fire sticks), namely, rupa (material form), vedana (sensation), samjna (cognition), samskara (disposition), vijnana (consciousness). The combined activities of these five functions is what accounts for our experience of subjectivity. But, since the skandhas are functions subject to conditions, the process which results from their combined activities, is also subject to conditions. What we call our “self,” (as the function of subjectivity) is a conditioned process. It is not the activity of an unchanging substantial entity that would operate on its own terms, independently of the specific contexts where it finds itself.

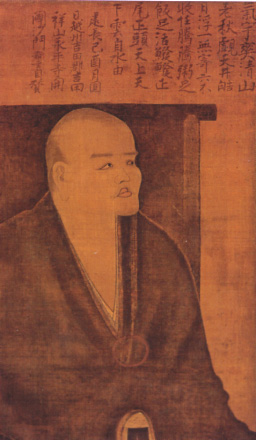

Though the Buddha used the term anatman, i.e., the opposite of the Upanisadic atman, to describe a “self empty of own being,” it does not mean that he had worked out his own teaching by way of theoretical thinking, taking the Upanisadic texts as a starting point. The insight into no-self had arisen from direct experience, more precisely at the moment when, having given up on his fast, he had remembered the deep calm which had come over him under the rose-apple tree. At that moment, it had become clear to him that no amount of willpower could trigger the breakthrough he had been hoping for. The breakthrough had only occurred when he had dropped the will, or rather, when “his’ will had dropped, that is, “his” identification with a substantial self had dropped. No-self had just “happened.” Centuries later, Dogen (13th century Japan) equated enlightenment with “dropping off body and mind,” while defining the “true self” as a “forgetting of the self,” terms which the Buddha could have used if the linguistic idiom available to him had not been the heavily conceptual, and abstract language of the predominent Brahmanical culture but, instead, the more poetic, concrete and intuitive language of the Japanese.

Sources

Richard F. Gombrich – How Buddhism Began (1996)

Govind Chandra Pande – Studies in the Origins of Buddhism (1957)

Nakamura Hajime – Ways of Thinking of Eastern Peoples (1964)